As it was seen, despite the fact that in a parliamentary democracy, in which the executive power is the government and the prime minister, while the legislative power is the parliament, the President of the Republic is the one who finally validates the decisions of all the others. Therefore, the authority deriving from his position is not as limited as it is presented to us - which means that his responsibilities are much greater than those of all the others (especially if he signs memoranda of servitude, at the expense of the national independence of country and the constitutional rights of its Citizens). Read the full text. It's big, but it's eye-opening. Give it to your children too.

Each country has its own special characteristics – usually not the means, with the help of which its citizens deal with destruction, pain and suffering. Among all, the most important is perhaps faith towards something – towards God, the state or any other concept and institution. For example, the Americans believe in the dream of success (American dream) - so they suffer uncomplainingly until they succeed, while they created a state and built a society, with the sole aim of material happiness. Precisely for this reason, wealth was essentially deified, neoliberalism flourished and the children of Chicago "grew up", at the expense of the welfare state.

On the contrary, the Germans believe in a hegemonic camp state, while their goal is not happiness, but the least possible misery – thus laying the foundations of the social welfare state, which is at the same time a police state (freedom and security are contradictory concepts). In this context, low pay is deliberately chosen from unemployment, excessive wealth is effectively "punished", the country is placed above all, while discipline is required from the Citizens - as well as absolute compliance with the strict rules of the state.

Continuing, Greeks unfortunately do not believe in anything but themselves - so they do not value their state and do not respect Institutions or social and other rules of coexistence, with our known results. Self-promotion trumps happiness, while envy is a natural consequence - since, considering everyone to be equal, if not better than everyone else, they do not accept the success of their neighbor (usually claiming that the success of "others" comes from luck, from corruption, from entanglement, etc.).

As it seems, the Greeks' faith in freedom is a thing of the past - at least judging by the political leadership, which admitted that it voted for the criminal memorandum of servitude, because the destruction from it will be less (the Greeks would have behaved accordingly Greek leadership in World War 2, if it chose the free invasion of the Germans, instead of resistance – since the first option would of course be less disastrous). Obviously, the virtue and courage of the Greeks, basic conditions for the preservation of freedom, no longer prevail - having probably been "repelled" by the good times of the last decades.

Concluding our introduction, Icelanders believe in self-determination and collectivity, which is not at the expense of individuality – having developed Direct Democracy (i.e. the active participation of the Citizens of a state in critical decisions, through referendums), into a basic political body of their country (which was founded in the 9th century AD by Norwegian settlers, while it is governed by the oldest still active parliament on the planet, the Althing, which dates back to 930 AD).

In this context, choosing to bankrupt the banks on their behalf regardless of the cost, the resistance of the proud, Celtic-born Icelanders better against the international moneylenders, who demanded the assumption of the debts of the financial institutions by the Citizens, was rather expected.

In general, they negotiated the debt crisis of their country (financial crises are not a shame for anyone, since almost all states have faced similar situations, many times in their history), with a criterion of how they could cope with the obligations that they would undertake – knowing that a successful negotiation depends on whether the debt becomes sustainable, which alone is valued by the markets.

So they did not give in to the demands of their creditors, like Greece, which unfortunately chose a debt write-off that continues to not be a sustainable solution and does not protect it from absolute bankruptcy (instead of the honest extension of the repayment period with low interest rates and with feasible installments , without any deletion) – while endangering the public and private property of its Citizens (national sovereignty), without any countermeasure whatsoever.

THE OUTBREAK OF THE CRISIS

Shortly after the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in October 2008, 85% of Iceland's financial system collapsed – turning the country upside down in just a few days. By that time the big three banks, which eventually failed (Kaupthing Bank, Landsbanki, Glitnir Bank), had acquired ten times the size of Iceland's GDP, despite having only been privatized in 2002 – and within a very short period of time they had acquired , with the help of immense leverage, numerous businesses in Scandinavia, the U.S. and in M. Britain.

Unlike now many other countries (Ireland, Germany, Spain, etc.), whose governments chose to bail out their failed banks (victims of the biggest heist of all time, by the USA), with the citizens' money, the Icelanders decided to let the banks fail – resulting in German, French and British banks, insurance companies and individuals (who had deposited money due to high interest rates).

Among the losers were the Citizens of Iceland, who had entrusted their savings to the three big banks. Only €20,887 was given per depositor, which was essentially the guarantee from the state, according to the European directive, which also applied to Iceland – since, despite the fact that the country is not a member of the Eurozone, it belongs to the European economic area, so is obliged to apply EU rules and treaties.

A large part of private savings was therefore lost, unemployment increased dangerously, the prices of basic necessities became unaffordable, while social services (education, health, etc.) literally ceased to exist.

Stock indexes collapsed, showing a greater drop than the US during the Great Depression of the 1930s, while private demand contracted, between 2007 and 2010, by 25%. The country's national currency, the Icelandic krona, was devalued by 50% against the Euro, while the budget deficit reached 13.5% (2008).

Total public debt rose to 130% of GDP (as high as $12.14 billion in 2009), causing 8,000 Icelanders (320,000 total population) to leave their country in search of work abroad. These immigrants made up 2.5% of the country's inhabitants – which means that, in an analogous process, Greek immigrants would reach approximately 275,000.

THE NEGOTIATIONS WITH THE NETHERLANDS AND WITH M. BRITAIN

In the case of banks, the major flaws and omissions of the financial policy of the European Union were clearly seen, since the guarantee funds for private deposits, according to the European directive, were only 47 million. € – a ridiculous amount, in relation to the activities of the country's banks on a pan-European level, since it corresponded to only 1% of the average bank deposits (€4.7 billion). That is, deposits, which banks had to keep as a guarantee for their customers' savings, were only 1% of deposits, according to the European directive - which, it seems, foresees the collapse of a single bank in a country, not the whole entire banking system.

But some European countries, such as M. Britain and the Netherlands, because they had found that the guarantee funds for their Citizens' deposits were too low, had increased them. In both of these countries, Iceland's Landsbanki operated through its online subsidiary Icesave. This bank, because it offered unbeatable interest rates to its customers, had managed to attract 300,000 British depositors and more than 125,000 Dutch ones. So when it went bankrupt, the governments of M. Britain and the Netherlands were obliged to compensate their Citizens, up to the amount of the guarantees, which they themselves had established - with the result that they then demanded this money from Iceland.

At the beginning of 2009, Iceland's negotiations with Britain and the Netherlands began - although it would be difficult to describe them as such, since they were essentially orders from the two European countries. Consequently, the final agreement was completely unprofitable for Iceland, since M. Britain demanded compensation of 2.4 billion pounds sterling, while the Netherlands 1.3 billion € – sums that essentially corresponded to 31% of the country's GDP (for example, in Greece these compensations would be, by comparison, approximately €68 billion). For each Icelander this amount would mean a charge of €11,000, plus interest of 5.55% from 1 January 2009 – an interest rate higher than what the two "opposing" countries were paying on their loans.

As it turned out, both the Netherlands and M. Britain, they not only wanted their claims to be paid, but also to earn more – by charging Iceland with usurious interest rates (something similar happened with the loans of the Eurozone countries to Greece, in 2010). Their only compromise with Iceland was to delay the payment (grace period) of interest and arrears until 2016 – while by 2024 all interest and arrears had to be repaid.

THE FIRST ADVERTISEMENT

The deal was decided by the government, which was elected in April 2009 – a coalition government of the Social Democrats and the Left-Green movement, which claimed it had to honor the promises of the previous conservative prime minister, from the autumn of 2008 (had guaranteed the full repayment of the banks' debts). The new prime minister wanted to quickly advance the contract with M. Britain and with the Netherlands, because she did not want to complicate the discussions on her country's entry into the Eurozone. Thus, he hastily brought the agreement to Parliament, where it was finally approved with 33 votes in favor and 30 against, on the grounds that "the state has continuity, so previous commitments must be respected."

However, the Citizens of the country had a completely different view – and as a result they constantly protested against the agreement. At the same time, 56,000 Icelanders (23% of the country's total voters), submitted a written protest to the President of the Republic, demanding a referendum. The President then acceded to the wishes of the Citizens, refusing to sign the law passed by Parliament – thus facilitating a referendum, the first since 1944, when Iceland's independence had been achieved.

As it was seen, despite the fact that in a parliamentary democracy, in which the executive power is the government and the prime minister, while the legislative power is the parliament, the President of the Republic is the one who finally validates the decisions of all the others. Therefore, the authority deriving from his position is not as limited as it is presented to us - which means that his responsibilities are much greater than those of all the rest (especially if he signs memoranda of servitude, at the expense of the national independence of country and the constitutional rights of its Citizens).

Continuing, this unexpected event immediately sounded the alarm in the strongholds of international usurious capital. Just the news that the taxpayers of a country would be allowed to decide for themselves whether and under what conditions they would assume the debts of their state created a great upheaval in the world financial markets. Of course, rating agencies immediately downgraded Iceland's credit rating – while the coalition government backed the deal, aiming to influence the referendum decision.

Instead, the conservative opposition positioned itself against the deal, aided by some commanding media – wanting in this way to convince that the two left-wing parties were incapable of governing (perhaps hoping that a 'No' vote would isolate Iceland from the international community, so it would cause the government to collapse). As we will see below, the opposition came out in favor of the second agreement – a fact that reminds us to a great extent of our country and the miserable "power games" of our own politics.

However, the free Citizens of Iceland were not at all interested in the political party games – voting "NO" because they reasonably believed that the treatment of their country by its creditors was completely unfair. So, the result of the referendum (06.03.2010) was overwhelmingly (93.2%) against the agreement – while only 1.8% were in favor. This fact forced the UK and the Netherlands to return to the negotiating table – as they could not in any way disrespect the wishes of the Citizens of Iceland, after such an impressive majority.

THE SECOND REFERENDUM

The new agreement with the "lenders", which was reached in a short period of time, was considerably more favorable than the first one - since the repayment would start in 2016, while the amounts of interest payments would never exceed 5% of Iceland's public revenue (for comparison, in Greece only interest accounts for approximately 30% of public revenue). The repayment period was extended to the year 2046 (from 2023 of the previous one), while the interest rate was reduced to 3% (any further comparisons with Greece, where, for example, annual interest payments would not exceed €3 billion, would be extremely disappointing for the political leadership and its negotiating "skills").

This time the Parliament, the government and the main opposition, decided with a large majority in favor of the agreement. However, because the honorable President of the Republic refused to ratify it again, i.e. did not sign the corresponding law, a new referendum was held - in which 59.77% voted again negatively (NO), while 40.22% voted positively, with the government to consider the result as its own defeat.

After the second "NO" of the Icelanders, both the British and the Dutch refused to negotiate again – announcing that they will now go to court, through the competent European Court (EFTA) in Luxembourg. Iceland, along with Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland, is one of the remaining member states of EFTA, which was founded in 1960 as the EU's "rival awe" (Denmark, Finland, the Austria, Sweden and Great Britain).

The EFTA control committee, which is based in Brussels, ruled in favor of M. Britain and the Netherlands, demanding that Iceland pay the debts of its bank (Icesave), towards its customers in the two countries - where the Parliament of Iceland replied that it had in no way breached the country's obligations, which derived from the European agreement (94/19/EG).

In any case, the Icelandic government had never refused to compensate the foreign private depositors of its failed banks for the damage caused to them. Instead, their claims have been prioritized over those of foreign banks and insurance companies – and for this purpose the assets of the bankrupt Landsbanki, estimated at 594 billion kroner, will be used.

DEALING WITH THE CRISIS

Iceland's most important weapon, in relation to the successful as it seems today, fight against the banking crisis, was undoubtedly the existence of a national currency. The devaluation of the koruna by 50% against the Euro greatly increased imports, while creating difficulties for foreign companies.

Several multinationals, such as McDonald's for example, have left the country – a fact of course extremely positive for small and medium-sized enterprises and for the state's revenues, since tax evasion by multinationals is one of the biggest "viruses" in the system (especially in the smaller countries of the Eurozone , whose businesses do not have the possibility to expand to other countries, as a result of which the tax avoidance of multinationals cannot be compensated, as well as the export of profits in the states where they are based – through our well-known transfer pricing).

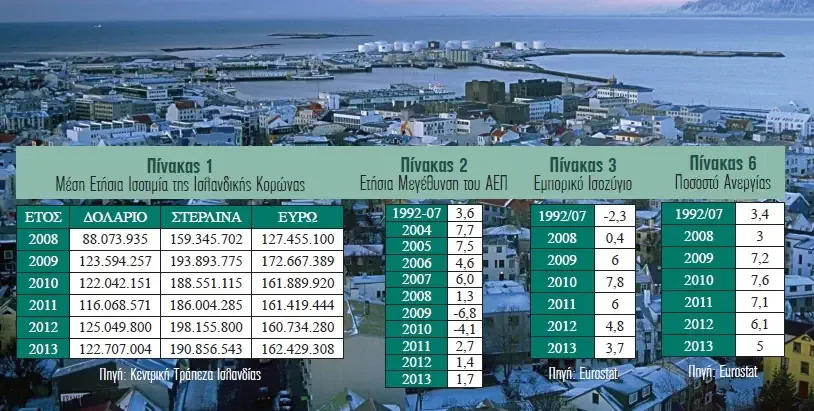

The high prices of imported goods naturally contributed to the growth of domestic industry, as well as increased exports and tourism – working just like in the "economic textbooks". Thus, despite the fact that the GDP reduction was of the order of -6.8% in 2009, in 2010 it was limited to -1.1%, while growth followed in 2011 (about 2.3%).

The government budget deficit fell to 9.3% in 2009 (from 13.5% in 2008), to 5.7% in 2010 and to 2.9% in 2011. Of course in terms of GDP per capita, Iceland has always been rich, as shown in Table I below:

TABLE I: Ranking internationally, per capita GDP and in dollars

Ranking Country GDP per capita

21 Iceland 43,226

19 Germany 44,556

22 M. Britain 39,606

24 Italy 37,046

30 Greece 27,875

Source: IMF, forecasts 2011

"Iceland succeeded because of the devaluation of its national currency, the instantaneous decision to let the banks fail, the smart economic policy it adopted, the exemplary punishment of those responsible, the determined and cool attitude of the Citizens, as well as its truly democratic polity: of digital direct democracy".

Analysis

Iceland has big differences, in relation to Greece – in terms of the causes that led it to the 2008 crisis, its non-participation in the Eurozone, its public debts, as well as its geopolitical position. We have also referred to the experiences that one could obtain from the country, looking for ways to escape Greece from the downward spiral of death, in which it has been trapped since 2010 - where since then the management of the crisis by all Greek governments has been literally hopeless.

There is absolutely no doubt that the memoranda that were imposed were criminal - in addition to the deletion, as it was launched, as well as the concessions that accompanied it.

However, this is a country that is the most suitable as an example, in terms of the adoption of the national currency by a state, such as Greece - because it is very small, with a poorly differentiated economic structure, with a very high dependence on imports (the percentage was around 45%, much higher than our country), with a budget deficit of -13.1% in 2008 (Greece -10.2%), as well as with current account deficit at -22.9% in 2008 (-14.9% then Greece).

So if it were documented that, even in such a country, the devaluation of its currency was effective as a basic strategy to deal with the crisis (those who claim that the drachma in Greece would not be devalued obviously do not understand that there would be no point in adopting it if this was not intended), then in larger states, with comparatively less dependence on imports, the adoption of their national currency would not be condemned by beforehand.

In this context, we remind you that in 2008 Iceland faced a huge financial crisis due to its banks - which participated in risky mortgage loans, as well as financial bets, with the result that their balance sheets have reached 1,000% of the country's GDP. Because they were now over-indebted in foreign currencies, Iceland's central bank was unable to support them – so 90% of the banking system collapsed within a week, and the government was forced to step in with emergency legislation to keep it from collapsing completely. the whole country.

Furthermore, despite the IMF getting involved, helping Iceland with a standby arrangement, the government did not adopt an austerity policy. Instead, it propped up the economy with very high fiscal deficits to generate growth – until private spending (consumption, investment) was able to fill the gap.

That is, it increased public investment and other government spending at the expense of the budget (exactly the opposite of what Greece did), effectively printing money – along with other measures, such as the liquidation of failed banks while guaranteeing their deposits, coupled with the imposition of capital controls.

In this case, one of the most important factors that contributed to Iceland's quick exit from the crisis was certainly the very strong devaluation of its currency – as shown in the graph, relative to the euro.

The Icelandic krona depreciated from 1:88.53 against the euro in September 2007 to 1:184.64 in November 2009 – until stabilizing in early 2014 when the economy recovered. It then even managed to appreciate slightly against the euro – which of course had a downward trend due to the Eurozone debt crisis.

The next developments

Continuing, this devaluation of -50%, which Iceland dared without delay, contributed significantly to the fight against the crisis - while the American economist D. Baker already mentioned the following in 2012:

"Because the country had its own currency, it managed to achieve a great deal by devaluing the krone against the currencies of its trading partners. This fact increased imports, drastically reducing their volume. The devalued currency lowered the prices of its own products, so it led to a strong increase in its exports.

Of course the above helped Iceland reduce its huge current account deficits gradually, resulting in a surplus after 2013 (graph) – something that continues to this day.

Continuing, the devaluation of the currency did not cause hyperinflation, despite the fact that the country was more dependent on imports than Greece - so logically the increased prices of imported goods should raise domestic prices and thus drive the economy into a vicious cycle "wage-price" which ultimately causes very high inflation.

The graph ( source ) shows that consumer prices increased in 2008 and 2009 as a result of the large devaluation of the koruna, but this trend did not continue – since they started to decrease already in 2010, reaching after 2014 lower levels than in 2002!

In this case, one could argue that this was due to the reduction in the real wages of workers, as a result of the rapid devaluation of the currency - which is only partially correct, since the fall in real wages (=purchasing value) was very large due to of inflation, but less than the nominal devaluation of the krone.

The graph below shows the evolution of real wages (real = minus inflation) of the private sector (blue curve), as well as the public sector (red curve) – where it can be seen that they actually fell from 2008 to 2010/11, but then they started to increase, while today they are 15% higher than in 2008 (+25% compared to 2005).

This fact is of course due to the appreciation of the koruna in relation to the euro after 2011, as we have seen in the first graph – something that did not happen only because of the general devaluation of the euro, since something similar was observed with most foreign currencies ( source ).

Finally, the growth rate of Iceland's economy proves that it has coped extremely well with the crisis – as seen in the graph, where its real GDP grew by 4.1% in 2015, as well as by 7.2% in 2016 in its currency.

Further, Iceland's results are obviously not a miracle, nor does it mean that there is a direct comparison with the Eurozone countries if they left the euro – since the country had its own currency and its own central bank before it plunged into crisis. while the state was not over-indebted, but its banks.

They are mainly due to its instantaneous decision to let the banks go bankrupt without assuming their debts, to the smart economic policy it adopted, to the exemplary punishment of those responsible, to the cool and decisive attitude of its citizens, as well as to its truly democratic government (digital direct democracy).

The Greek peculiarity

In conclusion, Greece is obviously not in the same position as Iceland, since it no longer has its own currency or its own central bank, it did not react immediately in 2010, it was imposed disastrous memoranda, it was handcuffed to the PSI, it tightened even more its bonds with the third memorandum, not only the state now owes huge sums but also private individuals while, most importantly, the its polity is purely oligarchic and not democratic – based on a constitution that has been constructed to serve the interests of the political gangs that rule it.

Therefore, it is possible for Italy and Spain to leave the euro if they want, much more difficult for Portugal or Cyprus, but Greece unfortunately does not have the luxury – unless it first resolves its (external after PSI, non convertible into drachmas) of its huge debt. Possibly daring to stop (postpone) payments within the Eurozone, with the simultaneous denunciation of the illegal loan contracts in the international court, with the compensation lawsuit against the Troika, with the exemplary punishment of those responsible for the coke tragedy. – if in the end the debt reduction is not approved despite the new measures and of course with the risk of being blackmailed to leave the Eurozone, in which case it should be properly prepared.

If the debt issue is not resolved, then the devaluation that Greece would have to pursue if it were to adopt the drachma, to be able to follow the example of Iceland, would send its public (and private foreign) debt skyrocketing, so it would default instantly – noting that Iceland's more than tripled, from 27.4% of GDP in 2007 to 95.1% in 2011, while the country was not out of the markets for seven years, as our country is today (Greece's 130% in 2010 obviously could not reach 360% – let alone 180% today).

However, this is not enough, since its citizens should also be united and determined like the Icelanders, have a corresponding democratic state, as well as a competent government - conditions that we at least do not see exist.

So, as much as one would like Greece to return to its national currency to escape the trap, it is not rational to dream while ignoring the cold reality – nor to blame those who cite it as supporters of the euro, since it is certainly not the case something like that.

Simply put, if the adoption of the drachma were the recipe that would free Greece from its enslavement and plunder, leading it out of the crisis, no reasonable person would object - which is not the case, if a sustainable debt solution is not previously secured.

At the European level, however, there is still hope, with the help of the ECB (the solution of solutions) – since otherwise Italy will collapse or leave the euro, while a similar solution (freezing part of the debts, thus increasing liquidity with inflationary consequences) , required for both the over-indebted USA and Japan, with the alternative of a world war.

Epilogue

As already mentioned, the lack of reaction of the Greeks, regarding the loss of their national sovereignty – as well as the "aggressive takeover" of their country by Germany, with the help of the "occupying" governments it installed successively, is impressive.

And even when they protest, their protest is about the multiple measures imposed on them – wages, pensions, taxes, etc., but not the scandalous privatisations, education, health or the politics of servitude and subjugation of the their elected representatives. Simply put, their reactions focus on the foreigners' mishandling of their misery – which, if it improved to some extent, would probably satisfy them.

We also remind you that some consider this to be normal, because the new class that dominates everywhere on the planet (elite, markets, etc.) is equipped with infinite "accounting" money, with manipulated news through ordered media, with systems of non-justice, with corrupt political parties, with entangled governments, with armies, with repressive forces, with de-blocking methods (education), etc. – so both the other peoples and the Greeks are not afraid, but they simply cannot do anything, no matter how much they want to. Therefore, all they have left is patience, until the system collapses – since historically even the strongest empires have declined and perished!

Having referred to the decalogue of crowd control, as well as knowing that coming to terms with defeat is much easier than fighting for victory, while fear completely disables people by burying them alive, we are of the opinion that there is nothing worse than acceptance of powerlessness: that there is nothing we can do because the system is all-powerful and invincible – while its greatest power is to pit one against another, one social group against another another, so that they cancel each other out.

So we believe that if the Citizens unite in demanding what is really theirs, without fear of the price and without exaggeration, it is impossible not to succeed - which in the case of Greece would mean the persistence of all Citizens in expelling the Troika and in the abolition of the memoranda, with the routing of the correct actions.

But we also believe that it is not fear or weakness that hinders the Greeks, neutralizing their healthy resistances - but that they no longer hope that they could be governed by correct politicians, while they have "drained" from the wider corruption of public life of the parties that are only interested in the province of power, of the prime ministers who never keep their commitments behaving like philarchs natives, the trade unionists who are indifferent to the closure of private businesses or the looting of public ones, the judges who do not judge as unconstitutional the memoranda but the reductions of their salaries and pensions, the media that care only for their interests, the entangled journalists who serve political parties or financial interests.

In this context, most Greeks did not object to trying something else, such as their administration by European institutions – in the hope that it would free them from domestic corruption, ensuring their survival. This is perhaps why they don't want the drachma, and also why they don't react and not fear – which will be seen when the foreigners want to push them even further, robbing them of what they have and don't have, so they will certainly revolt.

Three years later, despite the fact that the country borrowed from the IMF (but without implementing its recessionary policy, as practiced in Greece), the crisis is a thing of the past.

Unfortunately for all of us, Greece, like Ireland and Portugal, as well as all the other "victims" that will follow, does not have the luxury of a national currency - while any unilateral return of it, especially after the second servitude memorandum was passed, would it was extremely painful (for reasons that we have sufficiently analyzed, in several of our articles, without of course claiming to be infallible).

THE ROLE OF THE IMF

Our well-known fund manager traveled to Iceland in October 2008 to help the country – whose three major banks were collapsing within a week of each other. Fortunately for the Icelanders, their country was too small to be worth plundering, and its geopolitical position was also unimportant.

Thus, the help from the IMF, which approved credits of $2.1 billion (about 17% of its GDP, where in comparison for Greece it would be about €40 billion), alongside the transnational loans of the northern countries and of Poland, was in the right direction – since it did not impose the recessionary austerity policy, which was required by our country. The program now, drawn up in a short period of time and faithfully implemented, rested on four main pillars:

(a) A team of highly competent lawyers was assembled, who ensured that the nationalized banks would not assume their previous debts (the total loss of the markets, from the bankruptcies of the Icelandic banks, was about $ 85 billion. That is, about 7 times the GDP of the country – which would mean, by analogy for Greece, about €1.6 trillion).

(b) Another group of experienced economists undertook the stabilization of the exchange rate of the national currency – a fact that was finally achieved, although not completely, among other things with the help of controlling capital movements.

(c) The required loan funds for the first year were secured – while government payments were scheduled to be delayed.

(d) Banks were recapitalized, partially nationalized and the financial system was kept in operation – since without it the maintenance and development of the real Economy would have been impossible.

With this method, the recession was quickly fought, growth returned and new jobs were created – with the result that unemployment today does not exceed 7%. Iceland managed to return to the markets in June 2011, selling bonds worth $1 billion (8% of its GDP, in proportion to Greece it would be €19 billion), inflation fell to 7%, its public debt was reduced to 100% of its GDP, while bank debt was limited to 200% of the country's GDP.

AWARD OF JUSTICE

Icelandic society has decided to investigate in depth everything that led to the catastrophic bankruptcy of the country's banks. So the Parliament set up a committee, which delivered the first results of its investigation in April 2010. In this 3,000-page report, the culprits were precisely named: the three governors of the central bank, the director of the supervisory authority of the financial system , the former Prime Minister, as well as the Ministers of Finance and National Economy.

But responsibilities were also attributed to the social democrats, as for example to BJSigurdsson, who was finance minister for two years, before the outbreak of the crisis (in the case of Greece, the former prime minister, the head of the Central Bank, the ministers of finance, etc., would obviously be the respective culprits – while for the memoranda the following).

The Parliament did not of course cover the intertwining of the financial industry, Politics and the media – a fact that had contributed the most to the deregulation of the Icelandic banking sector. At the beginning of October 2010, he decided to bring former Prime Minister Mr. Haarde before a special court, considering him as one of the main culprits of the tragedy. For this reason, a special court, which was established in 1905 (Landsdomur), meets for the first time in its history.

According to many analysts now, Icelandic Citizens would not be able to easily defend themselves against the enormous pressures of M. Britain and the Netherlands, if their country were a member of the Eurozone - a fact that the Icelanders themselves probably know, since they are placed in opinion polls against the entry, with a percentage of 55.7% (refusing, as it is said, to become a protectorate of Eurozone).

According to the president of Iceland, Olafur Grímsson, the recovery is due to the fact that the Icelanders faced the crisis in a completely different way compared to the countries of the Eurozone: As he pointed out in an earlier

interview with Deutsche Welle:

it is only a financial and economic crisis, but a profound political and social crisis. And this led us to reforms in these fields. We let the banks fail. Iceland did not bail out its troubled banks. We sought to deliver justice and at the same time change the mechanisms of decision-making. The second reason for success is that we did not follow the Western prescriptions for dealing with the crisis.

I have often wondered why we treat banks as if they are the Holy Places of the economy. What sets banks apart from other businesses? Banks are big private businesses and when they make big mistakes they should go bankrupt. Otherwise, we give them the impression that they can take big risks without responsibility. It is not when they are successful that they make big profits and when they fail the taxpayer is called upon to foot the bill.

Of course it helped a lot that we had our own currency. We went ahead with the devaluation of the koruna and that was important. However, all the other moves we made were unrelated to the devaluation. We supported the welfare system. We empowered citizens to participate in political and social reforms. We let banks fail and built others. We would do this even if we were a member of the eurozone.

The Icelandic experience can act as a "wake-up call" for others. To make them reconsider the regime strategies of the last 30 years. The IMF's reaction to the Icelandic case was interesting. The IMF's crisis management program ended a year and a half ago. At the farewell meeting, senior IMF representatives admitted that much had been learned from the Icelandic experience.

Analysis

Iceland has big differences, in relation to Greece – in terms of the causes that led it to the 2008 crisis, its non-participation in the Eurozone, its public debts, as well as its geopolitical position. We have also referred to the experiences that one could obtain from the country, looking for ways to escape Greece from the downward spiral of death, in which it has been trapped since 2010 - where since then the management of the crisis by all Greek governments has been literally hopeless.

There is absolutely no doubt that the memoranda that were imposed were criminal - in addition to the deletion, as it was launched, as well as the concessions that accompanied it.

However, this is a country that is the most suitable as an example, in terms of the adoption of the national currency by a state, such as Greece - because it is very small, with a poorly differentiated economic structure, with a very high dependence on imports (the percentage was around 45%, much higher than our country), with a budget deficit of -13.1% in 2008 (Greece -10.2%), as well as with current account deficit at -22.9% in 2008 (-14.9% then Greece).

So if it were documented that, even in such a country, the devaluation of its currency was effective as a basic strategy to deal with the crisis (those who claim that the drachma in Greece would not be devalued obviously do not understand that there would be no point in adopting it if this was not intended), then in larger states, with comparatively less dependence on imports, the adoption of their national currency would not be condemned by beforehand.

In this context, we remind you that in 2008 Iceland faced a huge financial crisis due to its banks - which participated in risky mortgage loans, as well as financial bets, with the result that their balance sheets have reached 1,000% of the country's GDP. Because they were now over-indebted in foreign currencies, Iceland's central bank was unable to support them – so 90% of the banking system collapsed within a week, and the government was forced to step in with emergency legislation to keep it from collapsing completely. the whole country.

Furthermore, despite the IMF getting involved, helping Iceland with a standby arrangement, the government did not adopt an austerity policy. Instead, it propped up the economy with very high fiscal deficits to generate growth – until private spending (consumption, investment) was able to fill the gap.

That is, it increased public investment and other government spending at the expense of the budget (exactly the opposite of what Greece did), effectively printing money – along with other measures, such as the liquidation of failed banks while guaranteeing their deposits, coupled with the imposition of capital controls.

In this case, one of the most important factors that contributed to Iceland's quick exit from the crisis was certainly the very strong devaluation of its currency – as shown in the graph, relative to the euro.

The Icelandic krona depreciated from 1:88.53 against the euro in September 2007 to 1:184.64 in November 2009 – until stabilizing in early 2014 when the economy recovered. It then even managed to appreciate slightly against the euro – which of course had a downward trend due to the Eurozone debt crisis.

The next developments

Continuing, this devaluation of -50%, which Iceland dared without delay, contributed significantly to the fight against the crisis - while the American economist D. Baker already mentioned the following in 2012:

"Because the country had its own currency, it managed to achieve a great deal by devaluing the krone against the currencies of its trading partners. This fact increased imports, drastically reducing their volume. The devalued currency lowered the prices of its own products, so it led to a strong increase in its exports.

Of course the above helped Iceland reduce its huge current account deficits gradually, resulting in a surplus after 2013 (graph) – something that continues to this day.

Chart explanation: Development of Iceland's current account balance

Continuing, the devaluation of the currency did not cause hyperinflation, despite the fact that the country was more dependent on imports than Greece - so logically the increased prices of imported goods should raise domestic prices and thus drive the economy into a vicious cycle "wage-price" which ultimately causes very high inflation.

In this case, one could argue that this was due to the reduction in the real wages of workers, as a result of the rapid devaluation of the currency - which is only partially correct, since the fall in real wages (=purchasing value) was very large due to of inflation, but less than the nominal devaluation of the krone.

The graph below shows the evolution of real wages (real = minus inflation) of the private sector (blue curve), as well as the public sector (red curve) – where it can be seen that they actually fell from 2008 to 2010/11, but then they started to increase, while today they are 15% higher than in 2008 (+25% compared to 2005).

This fact is of course due to the appreciation of the koruna in relation to the euro after 2011, as we have seen in the first graph – something that did not happen only because of the general devaluation of the euro, since something similar was observed with most foreign currencies ( source ).

Finally, the growth rate of Iceland's economy proves that it has coped extremely well with the crisis – as seen in the graph, where its real GDP grew by 4.1% in 2015, as well as by 7.2% in 2016 in its currency.

Further, Iceland's results are obviously not a miracle, nor does it mean that there is a direct comparison with the Eurozone countries if they left the euro – since the country had its own currency and its own central bank before it plunged into crisis. while the state was not over-indebted, but its banks.

They are mainly due to its instantaneous decision to let the banks go bankrupt without assuming their debts, to the smart economic policy it adopted, to the exemplary punishment of those responsible, to the cool and decisive attitude of its citizens, as well as to its truly democratic government (digital direct democracy).

The Greek peculiarity

In conclusion, Greece is obviously not in the same position as Iceland, since it no longer has its own currency or its own central bank, it did not react immediately in 2010, it was imposed disastrous memoranda, it was handcuffed to the PSI, it tightened even more its bonds with the third memorandum, not only the state now owes huge sums but also private individuals while, most importantly, the its polity is purely oligarchic and not democratic – based on a constitution that has been constructed to serve the interests of the political gangs that rule it.

Therefore, it is possible for Italy and Spain to leave the euro if they want, much more difficult for Portugal or Cyprus, but Greece unfortunately does not have the luxury – unless it first resolves its (external after PSI, non convertible into drachmas) of its huge debt. Possibly daring to stop (postpone) payments within the Eurozone, with the simultaneous denunciation of the illegal loan contracts in the international court, with the compensation lawsuit against the Troika, with the exemplary punishment of those responsible for the coke tragedy. – if in the end the debt reduction is not approved despite the new measures and of course with the risk of being blackmailed to leave the Eurozone, in which case it should be properly prepared.

If the debt issue is not resolved, then the devaluation that Greece would have to pursue if it were to adopt the drachma, to be able to follow the example of Iceland, would send its public (and private foreign) debt skyrocketing, so it would default instantly – noting that Iceland's more than tripled, from 27.4% of GDP in 2007 to 95.1% in 2011, while the country was not out of the markets for seven years, as our country is today (Greece's 130% in 2010 obviously could not reach 360% – let alone 180% today).

However, this is not enough, since its citizens should also be united and determined like the Icelanders, have a corresponding democratic state, as well as a competent government - conditions that we at least do not see exist.

So, as much as one would like Greece to return to its national currency to escape the trap, it is not rational to dream while ignoring the cold reality – nor to blame those who cite it as supporters of the euro, since it is certainly not the case something like that.

Simply put, if the adoption of the drachma were the recipe that would free Greece from its enslavement and plunder, leading it out of the crisis, no reasonable person would object - which is not the case, if a sustainable debt solution is not previously secured.

At the European level, however, there is still hope, with the help of the ECB (the solution of solutions) – since otherwise Italy will collapse or leave the euro, while a similar solution (freezing part of the debts, thus increasing liquidity with inflationary consequences) , required for both the over-indebted USA and Japan, with the alternative of a world war.

Epilogue

As already mentioned, the lack of reaction of the Greeks, regarding the loss of their national sovereignty – as well as the "aggressive takeover" of their country by Germany, with the help of the "occupying" governments it installed successively, is impressive.

And even when they protest, their protest is about the multiple measures imposed on them – wages, pensions, taxes, etc., but not the scandalous privatisations, education, health or the politics of servitude and subjugation of the their elected representatives. Simply put, their reactions focus on the foreigners' mishandling of their misery – which, if it improved to some extent, would probably satisfy them.

We also remind you that some consider this to be normal, because the new class that dominates everywhere on the planet (elite, markets, etc.) is equipped with infinite "accounting" money, with manipulated news through ordered media, with systems of non-justice, with corrupt political parties, with entangled governments, with armies, with repressive forces, with de-blocking methods (education), etc. – so both the other peoples and the Greeks are not afraid, but they simply cannot do anything, no matter how much they want to. Therefore, all they have left is patience, until the system collapses – since historically even the strongest empires have declined and perished!

Having referred to the decalogue of crowd control, as well as knowing that coming to terms with defeat is much easier than fighting for victory, while fear completely disables people by burying them alive, we are of the opinion that there is nothing worse than acceptance of powerlessness: that there is nothing we can do because the system is all-powerful and invincible – while its greatest power is to pit one against another, one social group against another another, so that they cancel each other out.

So we believe that if the Citizens unite in demanding what is really theirs, without fear of the price and without exaggeration, it is impossible not to succeed - which in the case of Greece would mean the persistence of all Citizens in expelling the Troika and in the abolition of the memoranda, with the routing of the correct actions.

But we also believe that it is not fear or weakness that hinders the Greeks, neutralizing their healthy resistances - but that they no longer hope that they could be governed by correct politicians, while they have "drained" from the wider corruption of public life of the parties that are only interested in the province of power, of the prime ministers who never keep their commitments behaving like philarchs natives, the trade unionists who are indifferent to the closure of private businesses or the looting of public ones, the judges who do not judge as unconstitutional the memoranda but the reductions of their salaries and pensions, the media that care only for their interests, the entangled journalists who serve political parties or financial interests.

In this context, most Greeks did not object to trying something else, such as their administration by European institutions – in the hope that it would free them from domestic corruption, ensuring their survival. This is perhaps why they don't want the drachma, and also why they don't react and not fear – which will be seen when the foreigners want to push them even further, robbing them of what they have and don't have, so they will certainly revolt.

Three years later, despite the fact that the country borrowed from the IMF (but without implementing its recessionary policy, as practiced in Greece), the crisis is a thing of the past.

Unfortunately for all of us, Greece, like Ireland and Portugal, as well as all the other "victims" that will follow, does not have the luxury of a national currency - while any unilateral return of it, especially after the second servitude memorandum was passed, would it was extremely painful (for reasons that we have sufficiently analyzed, in several of our articles, without of course claiming to be infallible).

THE ROLE OF THE IMF

Our well-known fund manager traveled to Iceland in October 2008 to help the country – whose three major banks were collapsing within a week of each other. Fortunately for the Icelanders, their country was too small to be worth plundering, and its geopolitical position was also unimportant.

Thus, the help from the IMF, which approved credits of $2.1 billion (about 17% of its GDP, where in comparison for Greece it would be about €40 billion), alongside the transnational loans of the northern countries and of Poland, was in the right direction – since it did not impose the recessionary austerity policy, which was required by our country. The program now, drawn up in a short period of time and faithfully implemented, rested on four main pillars:

(a) A team of highly competent lawyers was assembled, who ensured that the nationalized banks would not assume their previous debts (the total loss of the markets, from the bankruptcies of the Icelandic banks, was about $ 85 billion. That is, about 7 times the GDP of the country – which would mean, by analogy for Greece, about €1.6 trillion).

(b) Another group of experienced economists undertook the stabilization of the exchange rate of the national currency – a fact that was finally achieved, although not completely, among other things with the help of controlling capital movements.

(c) The required loan funds for the first year were secured – while government payments were scheduled to be delayed.

(d) Banks were recapitalized, partially nationalized and the financial system was kept in operation – since without it the maintenance and development of the real Economy would have been impossible.

With this method, the recession was quickly fought, growth returned and new jobs were created – with the result that unemployment today does not exceed 7%. Iceland managed to return to the markets in June 2011, selling bonds worth $1 billion (8% of its GDP, in proportion to Greece it would be €19 billion), inflation fell to 7%, its public debt was reduced to 100% of its GDP, while bank debt was limited to 200% of the country's GDP.

AWARD OF JUSTICE

Icelandic society has decided to investigate in depth everything that led to the catastrophic bankruptcy of the country's banks. So the Parliament set up a committee, which delivered the first results of its investigation in April 2010. In this 3,000-page report, the culprits were precisely named: the three governors of the central bank, the director of the supervisory authority of the financial system , the former Prime Minister, as well as the Ministers of Finance and National Economy.

But responsibilities were also attributed to the social democrats, as for example to BJSigurdsson, who was finance minister for two years, before the outbreak of the crisis (in the case of Greece, the former prime minister, the head of the Central Bank, the ministers of finance, etc., would obviously be the respective culprits – while for the memoranda the following).

The Parliament did not of course cover the intertwining of the financial industry, Politics and the media – a fact that had contributed the most to the deregulation of the Icelandic banking sector. At the beginning of October 2010, he decided to bring former Prime Minister Mr. Haarde before a special court, considering him as one of the main culprits of the tragedy. For this reason, a special court, which was established in 1905 (Landsdomur), meets for the first time in its history.

According to many analysts now, Icelandic Citizens would not be able to easily defend themselves against the enormous pressures of M. Britain and the Netherlands, if their country were a member of the Eurozone - a fact that the Icelanders themselves probably know, since they are placed in opinion polls against the entry, with a percentage of 55.7% (refusing, as it is said, to become a protectorate of Eurozone).

interview with Deutsche Welle:

it is only a financial and economic crisis, but a profound political and social crisis. And this led us to reforms in these fields. We let the banks fail. Iceland did not bail out its troubled banks. We sought to deliver justice and at the same time change the mechanisms of decision-making. The second reason for success is that we did not follow the Western prescriptions for dealing with the crisis.

I have often wondered why we treat banks as if they are the Holy Places of the economy. What sets banks apart from other businesses? Banks are big private businesses and when they make big mistakes they should go bankrupt. Otherwise, we give them the impression that they can take big risks without responsibility. It is not when they are successful that they make big profits and when they fail the taxpayer is called upon to foot the bill.

Of course it helped a lot that we had our own currency. We went ahead with the devaluation of the koruna and that was important. However, all the other moves we made were unrelated to the devaluation. We supported the welfare system. We empowered citizens to participate in political and social reforms. We let banks fail and built others. We would do this even if we were a member of the eurozone.

The Icelandic experience can act as a "wake-up call" for others. To make them reconsider the regime strategies of the last 30 years. The IMF's reaction to the Icelandic case was interesting. The IMF's crisis management program ended a year and a half ago. At the farewell meeting, senior IMF representatives admitted that much had been learned from the Icelandic experience.

ICELAND TODAY

Iceland's banks have written off 20-25% of many households' loans, equivalent to 13% of the country's GDP, reducing the debt burden for more than a quarter of the population. This action, on the one hand, compensated the weakest of those who had losses on their deposits, after the bankruptcy of the banks, and on the other hand, it caused a partial redistribution of incomes, to the benefit of the small and medium class - something that ultimately "spilts" into the increase in consumption (GDP). , which is usually little affected by the very rich income strata.

In addition, a ruling by the country's highest court made loans linked to foreign currencies illegal – meaning that households no longer had to cover losses (from the devaluation) of the Icelandic krona. Without the debt write-off, property owners would buckle under the weight of their loans, after debt soared to 240% of incomes in 2008.

Iceland's economy will grow this year at a faster rate than the average for developed countries, according to with OECD estimates. Finally, real estate prices in the country are currently only about 3% lower than the prices in September 2008, just before the crisis (unfortunately, in the context of the brainwashing of Greeks by some organized media, a financial TV presenter claimed that, house prices in Iceland are 50% lower than they were in 2008!).

Finally, Fitch recently upgraded Iceland's rating, while stating that "its unorthodox policy to combat the crisis was successful." As it is said, Iceland's approach to dealing with the collapse was to always put the needs of its population above those of the markets.

In addition, a ruling by the country's highest court made loans linked to foreign currencies illegal – meaning that households no longer had to cover losses (from the devaluation) of the Icelandic krona. Without the debt write-off, property owners would buckle under the weight of their loans, after debt soared to 240% of incomes in 2008.

Iceland's economy will grow this year at a faster rate than the average for developed countries, according to with OECD estimates. Finally, real estate prices in the country are currently only about 3% lower than the prices in September 2008, just before the crisis (unfortunately, in the context of the brainwashing of Greeks by some organized media, a financial TV presenter claimed that, house prices in Iceland are 50% lower than they were in 2008!).

Finally, Fitch recently upgraded Iceland's rating, while stating that "its unorthodox policy to combat the crisis was successful." As it is said, Iceland's approach to dealing with the collapse was to always put the needs of its population above those of the markets.

CONCLUSIONS AND LESSONS LESSONS

The reference to the particular characteristics of states, as well as to the various economic crises around the world, would not be of much importance if there was no intention to learn from them. So as far as the leading powers are concerned, we would say that the sole objective of the USA, when they undertake crisis management with the help of the IMF, is profit – as well as their geopolitical interests. Therefore, the looting of both private and public wealth, as well as the "ranking" of weak economies in their countries of influence.

On the contrary, the aim of the northern European countries is to avoid damage – and especially Germany, plus the annexation of territories, since it has always been more interested in real assets, than in (useless) money. Therefore, it is important to secure both their banks and their public sector from any losses.

Finally, from Iceland's successful handling of the debt crisis, we conclude that the Citizens of a country have the power to change their destiny – as long as they take it into their own hands. The Icelanders managed to force referendums, with the help of the President of their Republic – which they managed to secure through peaceful demonstrations and the methodical collection of signatures (whereas in some other countries, mass abstention from workplaces contributed).

On the contrary, we Greeks unfortunately did not manage to impose referendums, as for example in relation to the interference of the IMF in the internal affairs of our country (May 2010), with the first criminal memorandum (July 2011) and with the murderous second one (February 2012) ). Besides, we have probably allowed the President of the Republic to avoid his great responsibilities – as well as the "gangs" of international moneylenders to terrorize us, including with their well-known actions during the mass protests. Of course, the exemplary punishment of those responsible for the crisis by the Icelandic Justice should not be underestimated – a "lesson", which should not be forgotten by the Greeks.

CONCLUSION

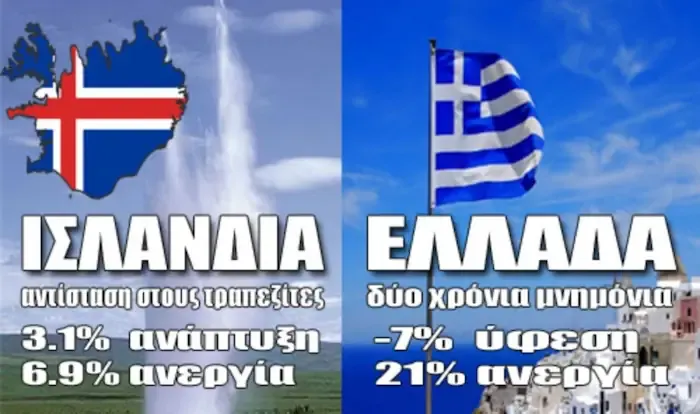

Iceland, at the start of the crisis (2008), had public debt at 130% of GDP and bank debt at 1,000% of GDP – while of course it had lost access to funding markets. Three years later (2011), the country returned to growth, reduced its public debt to 100% of GDP, as well as the banking debt to 200% of GDP, while unemployment was reduced to 7% and returned to the markets.

Greece, respectively, at the beginning of the crisis (2009), had public debt at 120% of GDP, bank debt at 23% and unemployment at 9%. Three years later, the public debt reached 170%, the banks practically went bankrupt despite their zero debt due to holding Greek government bonds, unemployment skyrocketed to 21%, recession to -7% and Parliament converted the entire mortgage debt – surrendering our national sovereignty and turning our homeland into a protectorate of Brussels.

After the debt cancellation (PSI), the new borrowing to recapitalize the banks, as well as the budget deficits (2012), public debt will be “reduced” to 155% of GDP (our “accounting alchemy” article) – continuing to it is much higher than in 2009 and of course unsustainable, despite Greece being criminally driven into bankruptcy (not forgetting the huge losses of the insurance funds, from the write-off).

As we have emphasized many times, what matters is not the amount of the debt as such, but the possibilities of its repayment – which continue to not exist in Greece, despite the (supposedly) successful exchange of bonds. Essentially, despite the fact that it is extremely positive to have your debt reduced by a bank by 30%, when at the same time it demands the mortgage of your house, condemning you to unemployment (recession), as a result, in the end, since you will not be able to pay the installments, to take your house, this is an obvious trap, for which it is rather an oxymoron to triumph.

After all, the unexpected "success" of the exchange (PSI), i.e. the great willingness of the bondholders to give them immediately, at 25% of their value, is quite eloquent in itself - since, if they did not believe that Greece would go bankrupt, they would be in no mood to lose €75, of the €100 they paid to buy them (hoping, as always, that we make a big mistake, relative to our pessimistic estimates and forecasts).

Perhaps we should add here that the new Greek bonds, those that will replace the previous ones, are already trading in the shadow markets, at 80-85% of their nominal value - despite being guaranteed by the EFSF, while under colonial English Law (mortgage etc.). This means that, regardless of what we believe, the markets see PSI as a complete failure (mainly because it does not make Greek debt sustainable), predict a disorderly default at the end of 2012, and do not believe that the new bonds will be paid at 100%. their face value.

Of course, the "poker of speculators" is not over yet, as we have already mentioned, for UK bonds, OSE etc. – with the hedge funds having taken up the final positions for the battle at the end of March (while no one can predict the results of the CDS payment or the lawsuits against Greece, on behalf of all those who lost their money, mainly from triggering of CACs).

In conclusion, so far it seems that we Greeks stoically accept our fate, without reacting and without caring about the future of ourselves, our country and our children - a fact that constitutes another "sad vanguard" of ours, which complements the already existing one: that we are the only country to date whose workers have accepted, without rebelling, the reduction of their nominal wages.

Of course, as K. writes. Castoriadis with the title "We are responsible for our History", "... In March 1968 one could say with confidence that the French population was completely disenchanted. But two months later came May....No one ever predicted a social explosion or a radical change in the attitude of the population. History is creation".

"May of '68", also known as "French May", describes the political and social unrest that broke out in France, during the months of May-June 1968. The events started with mobilizations of French schoolchildren and students, extended with a general strike of French workers (in which almost 70% of all workers participated) and finally led to a political and social crisis – which began to take on the dimensions of a revolution, while leading to the dissolution of the French National Assembly and the announcement of elections by the then president.

Some philosophers and historians have argued that, the uprising was the most important revolutionary event of the 20th century because it was not carried out by a single crowd, such as workers or racial minorities, but was a Palladian uprising, without racial, cultural, age and social distinctions.

Finally, the term "May '68" became synonymous with the change in social values. In France, it is considered a milestone for the transition from "feudal" conservatism to liberal, democratic ideas (equality, human rights, etc.). In Europe, it was an inspiration for similar social struggles, but also an occasion for a wider break with the party-centric state-dynasty.

Bibliography: Mitchell, Grunert, Tobergte

.webp)