- BEGINNING OF A NEW ERA

In 1764 Americans identified themselves as British subjects of King George III. Twenty years later, in 1788 they create a new country forged by revolution and war. The changes were significant. Thirteen states become a single independent federal state. The King and Parliament are abolished and replaced by the President, Senate and House of Representatives. Women get their first rights, and for black slaves, the revolution brought more freedoms, while in Massachusetts and Vermont, slavery was finally abolished.

The results of the American revolution were certainly many, but perhaps for many they were not enough. In reality many of the goals of the revolutionaries were never realized. The American Revolution was not only a conflict between American colonists and the British Empire for independence, but it was also a battle between different opinions within the revolutionaries. A battle over what the structures will be for building the new society.

The problems begin at the end of the "Seven Years' War" (1756 - 1763). The British defeat the French, while on the battlefields of the "New World" they also had the support of the American colonists, who participated as paramilitary groups alongside the "Red Coats". With the end of the war the British Empire seems to have achieved more than a military victory in its conquest. On the one hand, it put an end to the French threat to North America, and on the other hand, it seems that it also has the support of the American colonists.

But the "Seven Years' War" also had a high cost to the British Empire which someone would have to pay and obviously that "someone" was by no means the ruling class. In short the "Sugar Act" of 1764, the Stamp Act of 1765, the Townshend Taxes of 1767 and the "Tea Act" of 1773 essentially meant the transfer of American wealth to the American ruling class.

The American colonists continued to pay the British Empire and economic stagnation first and then underdevelopment inevitably ensued. The said development was against the slogan "No taxation if there is no representation". Thus the American colonists demand the right to participate in decisions. Between 1764 and 1775 the reactions against British taxation intensified.

Although only one in twenty American colonists lived in a city, a mass movement of resistance against the taxes imposed by the British Empire was gradually taking shape. The first episodes break out and the local collaborators of the British are terrified. In some cases British administrative buildings are destroyed. A part of the society also starts the boycott, while the most important personalities of the activist movement are organized in the "Sons of Liberty".

The organization spreads to at least fifteen cities and the episodes sometimes expand and the conflicts are fierce and bloody. Initially, the British seem to maintain a more passive attitude to the unrest, however, the final rupture occurs when in 1773 activists, posing as Native Americans, empty into the sea all the quantities of tea that had been loaded on an "East India Company" ship. .

Britain did not leave this action unanswered and sends troops to suppress the rebels by enforcing the law of the Empire. The throne requested that the perpetrators be transferred to London for trial. At the same time the Congress, which consisted of representatives of thirteen states, who were large landowners and merchants, decided to continue the tea boycott. The decision would be promoted by the local committees, while the militia is mobilized to support the said decision.

The "Revolution of the Elite" soon evolves into a "Revolution of the Middle Class". Revolution requires mass action to support radical demands. The elite have a lot to lose and their fear is a brake on the promotion of more revolutionary actions, as they are dependent on the current economic system and the profit it provides them. But this is not the case for the other classes. So the "trick" of the American elite is to keep up with the movement and maybe in this way it could limit its dynamics by calming the reactions.

American Revolution, 1775-1781: Lexington to Yorktown | American Independence, US Colonial History

He either sided with the political and military commanders of the King or with the movement as advanced by the Congress. In essence, the revolution takes place with these two options. "Dual Power", two rival authorities vie for power and political subjugation is unquestioned. Everyone will now have to choose which authority to submit to and everyone will have to take part. The first bullets were fired at Lexington, Massachusetts on April 19, 1775.

British soldiers (Red Coats) kill eight American militiamen and injure ten more. The war had just begun and the British army found itself besieged in Boston. The militias are soon supplemented by a "Continental Army," funded by Congress and commanded by George Washington. This body will develop into the military expression of the embryonic US. Militias defend their territories, but the "Continental Army" is waging a national war.

The British army wins most battles, with notable exceptions such as the battles of Saratoga in 1777 and Yorktown in 1781, yet the war is lost. This contradiction is due to three main reasons.

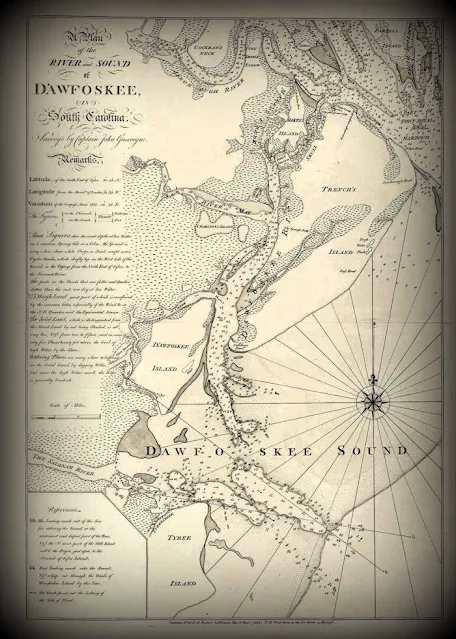

1) The first is the geographical one. The American colonies consisted of vast tracts of uncharted wilderness. These actually led to a significant logistical burden on the British and at the same time constituted ideal grounds for the resistance of the revolutionaries.2) Second, the revolutionaries have significant support from France, which initially supplies them with weapons and then carries out military operations both on land and at sea. As a result, a large part of the British forces had to be employed in maintaining the vulnerable sea line of supply.3) Third, the revolutionaries organized themselves politically and militarily for total war. The core of the rebels dominated the local committees and militias. On the contrary, the British could control areas only with the presence of the army.

Ordinary citizens fought for their ideals, freedoms and rights. The American Revolution was fueled by the vision of American citizens to create a "moral economy" and a "radical democracy" where the poor would have the same rights as the rich. The ideals of 1776 would be lost about a decade later in 1788. The "Declaration of Independence" (1776) recognized the equality of men and the inalienable rights of every citizen, such as life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

However, the Constitution of 1788 does not enshrine a "radical democracy" and a "moral economy", only property, the free market and the interests of the landed elite, merchants and bankers. The bourgeois revolution remained incomplete. Less than a century later hundreds of thousands of Americans would be killed on the battlefields of an even greater war, this time civil, for the right of equality among men.

The American Revolution essentially marked the beginning of a new era of world revolution. A year after the US Constitution was ratified, Parisians stormed the Bastille and the French Revolution had begun.

History: The American Revolution 1776 Documentary

The term American Revolution or War of Independence of the USA defines the war between Great Britain and its 13 colonies on the American continent (1775 - 1783). The armed struggle of the colonies against the oppressive metropolis was the culmination of the political processes of the second half of the 18th century. The English taxed their colonies heavily, which caused the discomfort of the inhabitants, especially the wealthiest who wanted to escape the financial tutelage of Great Britain.

The discomfort with the tax measures initially but mainly with the tax on tea which was maintained for reasons of prestige after the first reactions of the colonists, led the Americans not only to stop buying tea but also to destroy large cargoes of tea, throwing them into the sea, in Boston Harbor on December 16, 1773. The British responded by sending 4,000 troops to occupy Boston.

When English forces were sent to take military supplies from the town of Concord, Massachusetts on April 19, 1775, they met resistance from the Massachusetts militia at Lexington and then at Concord. The Americans managed to stop the British and force them back to Boston with heavy losses. The conflict had begun. All the colonies then mustered their militias and sent them to Boston.

The American forces surrounded Boston from the North, South and West, but left the port under English control, as a result of which reinforcements and munitions arrived. Many battles followed between the Continental army of the revolted colonies, of which George Washington was appointed commander-in-chief, and the English forces. The siege ended on March 17, 1776 with the victory of the colonial forces and the evacuation of the city by the English.

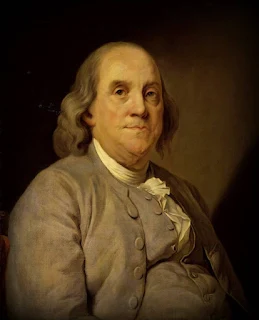

On July 4, 1776, a convention of Americans is convened in Philadelphia, where the Declaration of Independence is voted, which is based on the political ideas of the Enlightenment. Protagonists in drafting the Declaration were Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson. In the years that followed, the war became more general. The British were constantly sending reinforcements and the Americans were trying to keep the revolution alive. France sent financial aid to the rebellious Americans as well as troops.

The English army, led by General Cornwallis, finally surrendered at Yorktown, Virginia on October 19, 1781. The war officially ended with the Treaty of Paris on September 3, 1783, in which England ceded its territories to the United States. The last English troops left the continent on November 25, 1783.

- ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL SITUATION OF THE COLONIES

During the period 1607 - 1732, 13 colonies were established on the eastern coast of North America under English control. The settlers were mainly English, but also French, German and Swedish. Craftsmen and ruined small businessmen, victims of religious persecution and convicts, all were looking for a better fortune. The northern colonies had, in 1763, about 1,000,000 inhabitants, of which about 40,000 were black slaves.

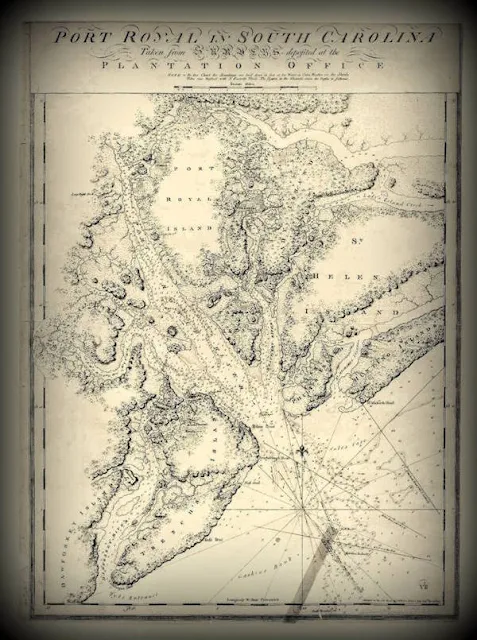

In economic conditions similar to those of western Europe, a dynamic agricultural economy had developed, while trade flourished with centers in the large cities of Boston, New York and Philadelphia. The first universities (Harvard, Yale, Princeton) were places for spreading the ideas of the Enlightenment. The southern colonies had, in 1763, about 750,000 inhabitants, about 300,000 of whom were black slaves. The economy was based on large plantations of tobacco, rice and cotton. The owners of the plantations were exclusively European settlers, who dominated economic and social life.

The land was farmed by black slaves who lived in miserable conditions. There were few large cities. Each state was governed by a governor, appointed by England. At the same time, there was an assembly of colonists that had a say in passing laws and approving taxes. Only some of the wealthy settlers had the right to elect and be elected to this assembly. The colonists were not represented in the English Parliament. Also, the foreign trade of the colonies was completely controlled by England.

The rapid growth of the colonies made many colonists, especially the wealthiest, resent England's financial tutelage. After the Seven Years' War of 1756 - 1763, England not only forbade the Americans to exploit Canada and Florida, which it had just captured, but also demanded new taxes from them to cover part of the war expenses. Colonists reacted by stopping buying English goods. England abolished most of the new taxes but retained, perhaps for prestige reasons, the tax on tea.

The colonists, however, were adamant, not only stopped buying tea from England but also proceeded to destroy English tea shipments. In response, England imposed trade restrictions on the port of Boston. Then, the Americans convened the Philadelphia Congress (convention) in September 1774, in which representatives from all the colonies participated. However, while the majority of Congress showed a willingness to compromise, the English King George III chose armed conflict.

The victory of American forces at the Battle of Lexington in April 1775 marked the final rupture. At the same time, militant pamphlets were circulating, written by radical intellectual followers of the Enlightenment, such as Thomas Paine, who argued that England had no right to exercise power over the colonies. At the same time, as the colonists realized their common elements, the American national consciousness was being born.

In this context, the Philadelphia Congress passed the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, a text that echoed the ideas of the Enlightenment and was drafted by Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin. The war that followed became known as the American Revolution or War of Independence. At first, the Americans, led by George Washington, faced problems.

After 1778, however, taking advantage of the opposition between the European powers, they made alliances with France, Spain and the Netherlands, which sought to limit England. The arrival of French troops in America affected the outcome of the conflict. The defeat of the English in the battle of Yorktown, in October 1781, also marked the end of the war.

Battle of Trenton 1776 - American Independence War DOCUMENTARY

The typical image of the American colonist as a man constantly moving through space in search of his "promised land" in the vastness of the American continent, is far from the reality that prevailed in the Colonies in the 17th and the first half of the 18th century. The vast majority of those settling in the British North American Colonies moved very slowly beyond the familiar environment of the eastern seaboard.

This fact, combined with the increased birth rate of families in the Colonies, created explosive situations in the second half of the 18th century. While settlers averaged 100 to 200 acres of land during the period of early settlement, by the last third of the 18th century available land in most parts of New England had dwindled to 40 acres. The fall in the average area of occupied estates indicates a gradual widening of social inequalities.

As available studies of the distribution of land and income in the British North American Colonies in the 17th and 18th centuries show, at the end of the colonial period the wealthy settlers were richer and more numerous than in the past, but the poor were also poorer and more than in the past. Widening social inequalities limited the opportunities for the participation of the "lower classes" in politics.

The debates over the qualifications of electors that characterized the political history of Massachusetts – and other Colonies – in the last third of the 18th century echo this concern of the poor about possible exclusion from politics. Indeed, estimates of taxable income in Suffolk County for 1786 reveal that 20% of city dwellers did not own enough property to be eligible to vote in state elections under the 1780 Constitution.

In this sense, US westward expansion "consolidated the image that had been formed of America as the land of mobility and opportunity at a time when it was beginning to be neither." If the growth of the colonial population in the first half of the 17th century was driven by immigration, the great demographic increase in the 18th century was mainly fueled by high birth rates. In 1607, when the first permanent settlement was established in Virginia, England had 4.3 million inhabitants.

Half a century later its population had reached 5.2 million, while at the end of the century, after a series of epidemics and bad harvests, it had been reduced to 5 million inhabitants. During the 18th century, however, demographic figures will recover: The English population reached 5.7 million in 1750, 6.7 million in 1775 and 8.6 million in 1800. During the same period, the Colonies were developing at a faster rate. From the 300 inhabitants of Jamestown, Virginia in 1610, the settlers had already reached 50,000 in 1650 and had exceeded 250,000 in 1700.

However, towards the end of the colonial period, when high fertility was the determining factor in the age and sex distribution, the ratio between the two sexes was more balanced. The first US national statistics showed that in 1790 the total population was 51% male and that the average American family consisted of 5.7 free persons (7 including slaves). Most of this population lived in rural communities while only 5% resided in cities with more than 8,000 inhabitants.

Urban centers such as New York and Philadelphia gathered already from the end of the 17th century 25 - 30% of the total population of the colony of New York and Pennsylvania respectively, although no colonial city could compare with London which gathered, as early as 1700, 11.5% of the total population of England. In the mid-18th century, Boston, the largest American city with a population of 15,000, was the eighth largest city in the British Empire.

In 1800, however, New York and Philadelphia, already over 60,000, could be compared to England's largest urban centers – only London, Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham had more population. Benjamin Franklin (Benjamin Franklin, 1706 - 1790) attributed the great increase in the colonial population in the mid-18th century to favorable economic conditions in the New World – especially available land – which encouraged early marriage.

Estimating that for every marriage in Europe there were two marriages in the Colonies, and for every four births in Europe there were eight births in the Colonies, he predicted, not arbitrarily, a doubling of the population of the Colonies every twenty years. Franklin, however, did not think that immigration contributed much to population growth and downplayed the importance of non-England immigration to America.

Today we know that at the beginning of the American Revolution only half of the colonists had English roots – the other half consisted of Germans, Irish, Scots, and slaves from Africa. The latter, despite their increased mortality and the unfavorable working conditions for natural reproduction to which they were subjected, will follow after 1740 the general upward trend that characterized the white population, reaching, in 1770, 20% of the total population of Colonies.

Historian Eric Foner reminds us that an understanding of social relations in colonial America presupposes not only an investigation of the relationship between free labor and slavery—a disconnect that was felt in the first half of the 19th century—but also a study of the intermediate levels between freedom and slavery that characterized the labor relations of the period.

In the second half of the 18th century, indentured laborers coexisted in the Colonies "with indentured servants, apprentices, domestic workers who were usually paid in kind, sailors forcibly conscripted into the British Navy and certain areas the commercial growers'. Indentured servants constituted "the majority of the non-slave labor force" before the American Revolution, "making up nearly half of the immigrants arriving in America from England and Scotland."

Available data, such as those concerning the arrivals of German immigrants in the port of Philadelphia between 1772 and 1835, indicate a great decline in recourse to the indentured labor system after 1820. In 1772, however, 56% of German immigrants who arriving in America via Philadelphia had signed "voluntary servitude" contracts with which they defrayed the costs of their passage to America. This figure, already extremely large, was reduced to 38% in 1785, rising again to 42% in 1815.

However, by the 1820s this institution had already withered away, representing less than 10% of Germans immigrants arriving in the US. The majority of the non-slave population were landowners who cultivated their land with family labor and with the help of indentured servants and slaves. In the colonial cities wage labor was widespread and steadily expanded after 1750. This was due to "population growth, limited access to rural classes, and the completion of indentured servants' time."

The economic depression that followed the end of the Seven Years' War "seems to have convinced many employers that the flexible working conditions of wage laborers, who could be hired and fired at will," was "economically preferable to investing in slaves or servants." . The exclusion of the Dutch from trade with British America, the Navigation Acts, which guaranteed the shipbuilders and shipowners of the Colonies the same privileges as their colleagues in England, and the abundance of raw materials, contributed to the flourishing of shipbuilding industry of New England.

The development of fishing, especially whaling, was also remarkable. The greatest, however, concentration of labor during the pre-revolutionary period was observed in the large plantations of the Middle and Southern States. In addition to the production of tobacco, cotton and other agricultural products, a number of artisanal activities flourished in them: from weaving and shoemaking, to flour mills and forges for the manufacture of agricultural tools.

If the large plantations are excluded, "most of the semi-skilled workers working on specialized lines of production under one employer were concentrated in the furnaces and forges." The factory complex founded by Peter Hasenclever in 1766 in New Jersey, which employed 500 German workers, included six blast furnaces, seven forges, an ore breaker, three sawmills, and a flour mill. Indicative of the development of metallurgy in the Colonies is the fact that in 1776, 14% of the world's crude iron production came from them.

Agreements not to import English products, with which the colonists reacted to the change in the taxation and customs regime of the Empire, facilitated in the 1760s the establishment of several industrial and craft units. Although the joint-stock company was not a common practice for financing industry, joint-stock companies in secondary production grew in the 1760s and 1770s.

Even though the real wages of workers in the Colonies exceeded their wages by 30% to 100% English, working conditions were not rosy. The seasonal nature of employment, particularly in New England, where fishermen, sailors, longshoremen, and artisans were forced to cease work for much of the year, compounded the problems created by fluctuations in the import trade.

The coastal communities, home to large numbers of widows and orphans who had lost spouses and parents at sea, were flooded with impoverished refugees from border settlements during periods of war. By the middle of the 18th century funds for the poor absorbed in cities such as Boston and New York up to 1/3 of the annual municipal expenditure. On the eve of the Revolution in Philadelphia, "the proportion of paupers was eight times as great as it had been twenty years before, and workhouses were built and filled as never before."

Washington's War (Full Movie) - General George Washington and the Revolutionary War

The New World, from 1739 to 1763, was the scene of continuous wars between Great Britain, France and, secondarily, Spain (the War of the Austrian Succession 1744 - 48, the Seven Years' War, or as it was called in America, War against the French and the Indians 1756 -1763). In these confrontations the colonists fought either for the preservation of the lands they already possessed, or for the conquest of new territories in the interior of America.

----------------------------

On the eve of the Seven Years' War, the Americans and British had wrested from friendly Indian tribes, such as the Iroquois of Western Pennsylvania, large tracts of land, which were taken over by companies such as the Ohio Company from Virginia, the Susquehanna Company of Connecticut and other "investors".

A condition, however, for the success of their plans was the repulsion of the French and Indians who refused to recognize their claims to the fertile lands of the Ohio, which, according to a Pennsylvania Gazette columnist, "could prove richer than the mining of Mexico". The end of hostilities found the victors of the war in a constant tug-of-war over the division of spoils and the organization of new territories, a tug-of-war that would only be finally resolved by a new war.

The need for the British administration to intervene in American affairs became more pressing when the British realized that the colonists were oriented towards a form of association which would enable them, on the one hand, to defend themselves more effectively against French penetration of the continent and, on the other hand, to deal with the Indians on the western frontier. John Adams (1735 - 1826) recalled that in 1756 "some were of opinion that we could defend ourselves better without England than with her, if we would only be permitted to unite and exercise the strength, courage, and skill us".

When representatives from eleven British Colonies met in the summer of 1755 in Albany, New York to discuss the problems posed by the as-yet-undeclared war with France, Benjamin Franklin submitted a plan for colonial unity, which became known as the "Albany Plan for the Union" ("Albany Plan of Union", 1755). Under it, a colonial government would provide for the "common defense and extension of British establishments in North America" and regulate Indian affairs.

A fact that revealed the desire of the colonists to tackle this sensitive issue regardless of the aspirations of the Imperial government. The president-general of the government, to be appointed by the Crown and a colonial parliament, could "declare war or peace with the Indian nations", regulate trade and "all purchases of Indian lands not within the boundaries of the individual colonies" , and to provide for the "new establishments until the Crown shall think fit to form them into separate governments."

In his Autobiography, Franklin argued that this plan, although unanimously approved by the Albany Conference, was not adopted by the colonial parliaments because it was "considered too privileged", that is to say, it delegated many powers to the Crown, "whereas in England" it did not it was supported because "it was judged to be very democratic". He believed that its adoption would prevent the "bloody struggle" that followed because it satisfied "both sides of the Atlantic," making the Colonies "sufficiently strong to defend themselves" without "the necessity of sending troops from England, and the subsequent pretext for taxing America'.

Three years later, young George Washington, a colonel in the Virginia militia, in the midst of the French and Indian war, pointed out to Francis Fauquier, assistant governor of Virginia, the need to regulate "the trade with Indians," so that the colonists would assume "a large share of the fur trade, not only with the Ohio Indians, but in time with the numerous nations possessing the inland regions," and, at the same time, "to thwart all attempts of individual Colonies which weaken the general system".

These views did not lead to tangible results, and conflicts between colonists and Indians made it imperative to maintain British troops on the frontier even after the end of the Seven Years' War. In one of these rebellions, in 1763, Indian tribes led by Pontiac, unhappy that their old allies and war losers, the French, had ceded their lands to the British and land-hungry settlers, destroyed in 1763 nearly all British outposts west of the Appalachian Mountains creating havoc in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia.

The prospect of the removal of the French from the continent meant for the colonists the beginning of a new period, where, undistracted by the rivalries of the European powers, they would concentrate on the exploitation of the hinterland. However, the more perceptive saw in the stronger military and political presence of the British in America the seeds of future problems. In 1758, when the colonists were planning to expel the French from the Quebec area, John Choate, a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives and a militia captain, wished for the failure of the operation.

Because, he explained, "once the English conquer Canada they will establish their presence and treat us worse than the French and Indians ever treated us." And John Adams, who years later recalled these prophetic phrases in a letter, adds: "Not two years have passed since then, when the British Government ordered writs of assistance to be put into effect for the violent searching houses, warehouses, ships, stores, barrels in search of contraband."

Shortly after the introduction of search warrants, the Court of Common Pleas in London outlawed the use of general warrants that could include those of the American Colonies. John Dickinson (John Dickinson, 1732 - 1808), in his famous Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania (1767 - 1768), called this provision "destructive to liberty, and clearly contrary to the common law, which always regarded a man's house as his fortress, or a place of absolute security.'

Although the colonists had not yet realized the necessity of joint action against the "violations" of the metropolis, when this action led the relations of the metropolis and the Colonies to an impasse, the transition from findings to practice turned out to be particularly painful. In this respect, the different course of action followed by John Adams and John Dickinson against the new reality marked by the armed conflict is characteristic.

In the 1760s, the British North American Colonies were the scene of intense internal conflicts even before they were colored by the reactions against the colonial policy of the British governments after the end of the Seven Years' War. The rivalry between the wealthy families of New York, the Anglicans de Lancey (De Lancey) and the Dissenters (the "disputing" with the official Anglican Church) Livingston (Livingston), the confrontations of the Quakers with the Party of Proprietors.

And all along with the Irish and Scottish immigrants of Pennsylvania, the disputes in Massachusetts between Thomas Hutchinson and James Otis the Younger, to mention only a few typical cases, contributed to the political and moral delegitimization of the dominant social groups in local communities.

However, more importantly, the mobilization of the popular element through mass political rallies and the systematic use of the press in shaping public opinion caused "a profound change in the traditional patterns of political behavior". Both the disenfranchised and the disenfranchised "became more active on the political stage than ever before, even if that activity often amounted to cheering decisions made by a few leaders."

After the end of the Seven Years' War, the British government was faced with a serious dilemma. All the indications—the great public debt, the relations of the Indians with the settlers, and of the latter with the metropolis—pointed to the necessity of a permanent military corps in the Colonies, much larger than that which existed before the commencement of the war.

British commander-in-chief Jeffrey Amherst, who had "distinguished himself" in suppressing the "Pontiac Conspiracy" by offering the Indians bedding from the smallpox hospital, estimated 10,000 soldiers were needed to keep the peace with the Indians and to deal with land encroachments, smuggling and robbery. On the other hand, the social conditions in the metropolis did not allow the imposition of new tax measures for the maintenance of the Colonial army, and this was shown in 1763 by the resort to the use of the army to collect the Cider Tax intended to cover part of the war expenses.

The colonists, therefore, had to contribute an ever larger portion of the £300,000 required annually for the maintenance of the British army in America. A first reform of the colonial administration was attempted in 1763 (Proclamation of 1763), when the British government turned the entire area beyond the Appalachian Mountains into an "Indian camp" while simultaneously prohibiting the purchase and sale of land. This meant that the growing population of the Colonies would not be channeled to the West, but to the North or South, where the connection with Britain was closer and the system of commercial exchange which enriched the metropolis flourished.

The colonists, however, did not intend to comply with the instructions of the Imperial government. Moreover, a series of concessions made by the unstable British governments of the period to land speculators created the belief that the reforms were temporary and that the more energetic of the colonists should establish claims on the lands of the West in order to later reap the benefits.

Characteristic of the way in which these prohibitions were treated is the fact that Washington, in September 1767, confided to his fellow soldier and land appraiser William Crawford that "I never considered the proclamation of 1763 but a temporary measure to pacify the Indians, which must naturally subside in a few years especially when the Indians consent to our possession of the lands.' In this context he advised him not to "neglect the existing possibility of locating good lands and registering them as his own".

Washington, who claimed large tracts of land near the Ohio River that had been granted to officers of the Seven Years' War, aimed to "secure a good deal of land" ("my plan is to secure a good deal of land"), a plan that at the same time it represented the dream of many settlers. In the meantime, the Crown, with a series of economic and administrative reforms, attempted to increase the revenue it derived from the colonies and create a structure capable of administering them.

Final Battle - The Patriot

In this context, the British governments did not only impose duties on products imported into the Colonies - this was attempted, for example, with the Sugar Act (1764) which taxed clothing, sugar, tobacco, coffee and wine - but also in other more "direct" burdens such as the famous Stamp Act (1765), i.e. the law that imposed the stamp tax. The most oppressive provision of the Sugar Act for the colonists was the reduction of the duty on molasses imported from the British West Indies.

This measure, aimed at cracking down on smuggling and thereby increasing customs revenue, upset those who imported duty-free molasses from the French and Spanish West Indies to make rum. Colonists' rum was traded on the coast of West Africa for slaves, who were sold in the West Indies for sugar and molasses, which was imported into the Colonies to fuel this "infamous triangular trade" but also the colonial economy with its precious metal currency , before the latter was channeled to England against industrial and other products.

The metropolis aimed not only at curbing the smuggling of molasses, but also tea, whose import monopoly was held by the East India Company. The tax on tea, one of the Crown's main incomes, was reduced when it was re-exported to America. The fact, however, that the price of English tea was twice that of Dutch tea, which was imported into the Netherlands from its colonies duty-free, favored the smuggling of this valuable product.

The government of Lord Chatham (William Pitt the elder, 1st Earl of Chatham, 1708 - 1778) abolished in 1767 all taxes on tea re-exported to America, but which would be subject to a three-pence duty paid to the American customs. This measure was intended to increase customs revenue by restricting smuggling but also to regain control of all transit trade to and from the Colonies from the Royal Navy, an objective of strategic importance, as already pointed out in 1765 by Thomas Whately (Thomas Whately), the then British Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Attempts to enforce the law and restrict tea smuggling so that the East India Company would become the sole supplier of tea to the American Colonies was a constant source of confrontation between the colonists and the metropolis until the start of the Revolution. However, the disturbance caused by the imposition of the Stamp Act 1765 first shaped the social and political conditions in which the colonists became aware of their power and began to discuss the possibility of separation from the metropolis.

This Act, introduced in 1765 by Chancellor of the Exchequer Lord Grenville, was imposed on all legal documents, journals, newspapers and pamphlets printed in the American Colonies to "further defray the expenses of the defence, protection and security" of the Colonies. The tax would be collected in pounds sterling while offenders would be tried by naval courts without a jury, which made it more onerous.

The reactions caused by the Stamp Act were such that the moderate Boston lawyer and politician Thomas Cushing (1725 - 1788) warned Massachusetts Assistant Governor Thomas Hutchinson a few months after its enactment that "a spirit of equalization ( ``levellism'') seems to run throughout the country and there is little distinction between high-ranking and low-ranking officials."

In the fall and winter of 1765 demonstrations against the Stamp Act swept every city in North America, and tax collectors were under such pressure that they often fled to other Colonies for fear of their lives. Those rulers who tried to enforce the law faced the wrath of the "mob".

The measure of the reactions is provided by forcing New York's Assistant Governor Cadwallader Colden (1688 - 1776) to take an oath in November 1765 that he would "never, directly or indirectly, attempt to introduce or enforce the Act of of Paper, that with all his powers he will prevent it from being applied here, and will endeavor to obtain a revocation of it in England." The threat of the "mob" had already been faced by the mayor of the city, who sought safer refuge on a warship and then in England.

Under these circumstances Colden, like most officials in the Colonies, did what seemed to them the most prudent solution: he did not apply the law. In Boston, where the "lower classes" of the city had formed a common front against the enforcement of the law, which forced the more moderate middle classes to join them, the intensity of the popular reaction was such that Governor Bernard (Francis Bernard, 1712 - 1779) observed that the "mob" sought not only the abolition of the law, but also of all "distinction between rich and poor."

The momentum of the protests in Boston is also due to the fact that the Stamp Act found the city in the throes of a long depression that had hit its middle and poorer classes, especially those employed in the shipbuilding industry. Large increases in spending on the poor and delays in tax collection were signs of this recession.

After all, the popularity enjoyed by Samuel Adams (Samuel Adams), orchestrator of the popular reaction against British policy, was also due to the fact that as a tax collector he had shown special tolerance towards his fellow citizens. In Philadelphia, by contrast, where unity among small merchants, artisans, and "laborers" had not been achieved until at least 1770, the reactions were less acute and effective than their counterparts in Boston.

The position of the metropolis became more difficult because even the distinctions made by the colonists between illegal "internal" taxes, such as e.g. the Stamp Law, and the tolerable "external" taxes, i.e. customs duties, or between "the regulation of trade", which was not disputed, and an "income tax", which was considered "unconstitutional" because it was imposed by the members of a Parliament, in whose election they did not take part, seemed not to be obvious.

The colonists believed that the very monopoly of colonial trade, to which the metropolis owed a significant part of its power, was unjust regardless of any individual fiscal regulation. This, after all, had been pointed out in pamphlets published in the Colonies in the 1760s. In 1763, James Otis the Younger (1725 - 1783), who resigned as Solicitor General in the Boston Admiralty Court because of the issuance of search warrants for the confiscation of contraband, he answers those who recalled the great expenses incurred by the metropolis for the protection of her Colonies as follows:

“The last conquests in America, afford the Colonies only a security against the disastrous raids of the French and Indians. Altogether our trade has not benefited one shilling," on the contrary, he emphasizes, "the income of the Crown from American exports to Great Britain is colossal. No manufactures of Europe except British may be imported. In his pamphlet with the characteristic title The Rights of the British Colonies Assured and Proved (1763) he points out the absurdity of the distinction between internal and external taxation.

Taxing the trade of the Colonies is unjust because it imposes "a heavy burden on the maintenance of a swarm of soldiers, customs officers, and a fleet of patrolling ships." What, he asks, would prevent Parliament from "imposing stamp duty, land tax, tithes for the Church of England, and similar taxes without limitation?" All taxes, therefore, whether "external" or "internal," are unacceptable if imposed without the consent of the colonists.

The clarity with which he sets forth the relationship between representation and taxation recalls Locke's Second Treatise on Government: The colonists, living under the protection of "the best (state) of all that is now on earth" , enjoy certain fundamental rights, such as that they cannot be taxed without their consent, and that they "must be represented in some proportion to their population and property in the great Legislature of the nation."

JOHN ADAMS 2008

Nevertheless, Otis was not ready for a more active policy, such as the colonists would attempt in the late 1760s. If his countrymen declared in 1776 that "the history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injustices and usurpations which had for their immediate object the establishment of an absolute tyranny in these States," Otis recognized in 1763 as a "principle" that "every good subject is bound to believe that his King does not intend to commit no evil."

This", he concludes, "is a Constitution! To maintain what has cost oceans of blood and money in every age from external or internal enemies.' Otis protests not because America is under the yoke of the British Constitution, as many colonists were a decade later, but because that Constitution does not apply to the Colonies. His analysis of the British Constitution is taken seriously during the arduous process that would lead in the late 1780s to the drafting of the American Constitution.

Two careful readers of it in the political juncture of the 1780s are Madison and Hamilton. What causes them terror is not the arbitrariness of a tyrannical power, but the anarchy of "democratic" passions. What cost "oceans of blood and money in every age" are property rights, especially those in their most "material" and "earthly" form.

Otis, after all, states in 1763, in a paragraph reminiscent of the Federalist, that in some Colonies "the operation of the executive power has not been successful" and that "the people are represented as factional, seditious, and having a particular inclination towards democracy, so that it has refused passive submission to the edicts of the Colony, as happens in the provinces of a Turkish Pasha."

Otis defended "the natural and almost mechanical loyalty (of the colonists) to Great Britain" regarding the prospect of "an independent Legislature, or State" in the American Colonies as the "greatest rebellion" that could ever occur. "If the choice could be offered between Independence or submission to Great Britain on terms of absolute slavery", the colonists, he assured, "would accept the latter".

If Otis, in declaring the right of the colonists to judge of the propriety of an Act of Parliament, does not question the right of Parliament to legislate for its subjects, Silas Downer boldly declares that "the Parliament of Great Britain (does not) has any legal right to make any laws that bind us, for there is no source from which such a right can be derived."

The Discourse on the Tree of Liberty (1768) is interesting not only because it comes from a distinguished lawyer and statesman of Rhode Island, one of the most radical Colonies in the 18th century, but also because without explicitly referring to "Independence," the style and his determination show that this fate seemed foreordained to many colonists at the time. Downer emphasizes that governments must ensure "the natural liberty of individuals, which no human creation has a right to deprive them of."

Therefore, "the people must not be governed by laws in the creation of which they have had no part, nor their money taken from them without their consent. This privilege is internal and cannot be granted by anyone but the Almighty.' The British Constitution, in fact, in which "the possession of property, especially immovable property, gave the subject the right to participate in the government", made the participation of the colonists more imperative in the passing of the laws of Parliament.

“The Americans,” he observes, “have such property and estates, but they are not represented. It is therefore clear' that Parliament 'can pass no law binding us, but that we must be governed by our own parliaments in which we may participate either in person or by representatives'. If Otis focuses his attention on the negative effect that the British laws had on the commercial relations of the colonists with the metropolis, Downer emphasizes the detrimental effect of the regulations on the industries of the Colonies:

"We have been forbidden to buy any goods or manufactures from Europe except from Great Britain, and to sell ours to foreigners, with the exception of certain trifling goods. But in trade between us they can set prices, which amounts to a tax in their favor." He considers equally absurd in a country where "iron abounds" the prohibition of Parliament "to process it for the manufacture of plates and bars in factories." These restrictions," he concludes, "constitute violations of people's natural rights and are utterly void."

Some years later, in February 1775, when armed conflict between the Colonies and the metropolis seemed very likely, John Adams pointed out that “America will never consent to Parliament having any jurisdiction to alter in any way its constitutions. If America", he underlined, "has a population of 3,000,000 and the total possessions (of Great Britain) of 12,000,000, it must send a quarter of all members to the House of Commons", while one of its four sessions it must be done in the Colonies. Otherwise, he warns, "Great Britain will lose her Colonies."

The tension in metropolitan-Colonial relations observed in the 1760s was not simply a side effect of the new British fiscal policy after the end of the Seven Years' War, thus a return to the pre-1763 regime, which would have left unchanged the structures of trade with the Colonies, it was not enough to solve the problems on both sides. Even those who were willing to accept the "old regime" of British privilege were equally unwilling to compromise the control mechanisms promoted by the metropolis.

On the other hand, the British governments were not prepared to accept in the name of the colonists' invocation of their fundamental rights as English citizens any "massive violations of the laws of trade", which undermined "the integrity of the mercantile system itself". Colonial reactions against this system were seen in Great Britain as a denial of its right to exist as a colonial power.

The metropolis had consciously discouraged the "industrialization" of the Colonies not only by depriving the "vital space" of its crafts, i.e. the colonial market itself – for example, the Wool Act of 1699 while allowing the manufacture of woolen goods in the Americas, it forbade their export beyond the borders of the colony in which they were made – but also controlled the flow of skilled labor to prevent the transfer of know-how to the New World.

It is no coincidence that in 1699, the British Board of Trade prohibited the immigration of workers employed in the woolen industry, while similar restrictions on the immigration of skilled artisans were imposed in the textile industry (1750, 1774, 1781), machine building (1782 ), the iron industry and coal mining. From the middle of the 17th century the initially prevailing perception of the colonies as places to settle England's surplus and socially undesirable population was replaced by the belief, expressed in 1768 by the commander-in-chief Thomas Cage, that "it would be good to emigrate from Great Britain, Ireland and the Netherlands to be prevented.

And that our new Colonies be inhabited by the population of the old, as a means of weakening them, that they may have less power to do Evil.' Although the metropolis continued to send the unemployed, the poor and convicts to the Colonies, as it saw conflict looming it erected greater barriers to immigration, indeed in 1774 it imposed a tax of £50 on prospective settlers from Great Britain and Ireland effectively forbidding further migration to the New World.

George Washington" (1984) - Complete George Washington Biographic Mini-Series

The tariffs imposed by Townsend in 1768 - 1769 were met by the colonists with a boycott of British goods, which caused their sales in the Colonies to drop dramatically. In February 1768, the colony of Massachusetts, which had initiated the policy of "non-importation" from Great Britain, issued a circular declaring the Townsend Tariffs unconstitutional. When the Legislature refused her recall, the new Colonial Secretary, Lord Hillsborough, dissolved it.

George Washington II: The Forging of a Nation (1986) - Complete George Washington Mini-Series

This measure aggravated the already explosive atmosphere in Boston and forced Crown officials to seek the help of the army to enforce the recent laws. The seizure, in 1768, of the ship Liberty, which belonged to the wealthy merchant and prominent figure in the anti-tariff movement Townsend, John Hancock, caused "the most terrible demonstrations in the history of Boston." In the late 1760s, a military force of 4,000 armed men settled permanently in Boston, fueling the colonists' fears.

When a group of soldiers terrified by the settlers' protests opened fire on them, killing five civilians, "the Boston Massacre," which would be depicted in hundreds of prints, engravings, and engravings, inflamed passions across America. In the meantime, the government of Lord North (Frederick North, 1732 - 1792), unable to collect the estimated sums from the new tax measures, revoked the Townsend duties in 1770 leaving only the tax on tea "as a sign of the superiority of Parliament and clear declaration of his right to govern the Colonies'.

Despite the two years of relative calm that followed the withdrawal of tariffs, the sinking of the British schooner "Gaspee" off Rhode Island in 1772 and the news of the transfer to Britain of all suspects for trial brought the fears of the colonists for violating normal court procedures. The confrontation came to a head the following year when the British Parliament granted the financially struggling East India Company the exclusive right to sell tea in America.

This event caused a rift in the colonists' trading community: those members of it who were excluded from the right to sell tea, which was selectively granted by the Company, more strongly resisted British rule. The destruction of a large batch of tea in the port of Boston by a group of colonists disguised as Indians provoked the immediate reaction of the North government, which now demanded, together with the majority of the House of Commons, the exemplary punishment of the culprits.

The passing of the so-called Coercive Acts (31-3-1774), which affected colonial trade (blocking the port of Boston until compensation was paid for the damaged tea) and created an authoritarian political framework (strengthening the executive power and the now Crown-appointed Upper House of Massachusetts, confiscating houses for the soldiers' barracks and entrusting the new Governor, General Thomas Cage, with the appointment of judges and police).

It pushed the colonists toward the option that few had been willing to accept in the past, that of armed confrontation with the metropolis. The news of the substantial abolition of the colonial charter of Massachusetts, which had established a broad framework of self-government since 1691, and the prohibition of any public assembly without the approval of the Authorities shocked America. Even the conservative Presbyterian clergy of North Carolina protested at this unwarranted display of authoritarianism on the part of the Imperial power.

If Parliament could repeal the Massachusetts charter, then, one of them asked in July 1775, “what security can we have for the lands and improvements we have made under these charters? Certainly, if they can cancel the colonial charters, they are able to cancel all our notarial deeds and all our land tenures or any other privilege.”

In June of the same year, the Quebec Act, which secured the religious rights of the Catholic inhabitants of Canada and "transferred to the province of Quebec the control of the Indian trade in the vast region between the Ohio and Mississippi rivers", made noise those who looked after the lands and trade of the region, but also the zealots of the Protestant faith. This concern was vividly described in October 1774 by New Hampshire's general and representative in Congress, John Sullivan, who considered this law "the most dangerous to American liberties."

"For," he explains, "if we remember what a perilous condition the Colonies were in at the commencement of the last war (Seven Years' War) with a number of these Canadians in our south, assisted by powerful Indian nations, determined to exterminate the Protestant race from America, and think that (Canada) may become a refuge for Roman Catholics who will always favor the privileges of the Crown, we must suppose our situation now to be infinitely more dangerous than it was then.'

If the situation in the American Colonies in the late 1760s seemed to be getting out of the control of the metropolis, equally serious were the problems facing the governments of the period in Great Britain itself. The accession to the Throne of the skeptical Parliament of George III (1760) led to weak and short-lived governments, which lacked the necessary political cohesion and social trust to manage the problems of an Imperial power.

The successive governments of Lords Bute (John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, 1713 - 1792) and Grenville (George Grenville, 1712 - 1770), of the portion of Rockingham (Charles Watson - Wentworth, Bʹ Marquess of Rockingham, 1730 - 1782) and of Lord Chatham, dealt with the problems of the Colonies spasmodically as shown by the inability to resolve the thorny issue of a legally tendered colonial paper currency. In Great Britain itself, the entry of the "mob" into politics frightened the young ruler who in 1763 observed that there were "insurrections and disturbances in all parts of the territory".

- CAUSES AND CONDITIONS OF THE REVOLUTION

1) Political dependency of England (Administrative dependency).2) Economic dependence on England (They were obliged to have trade relations only with the metropolis i.e. England, imposition of taxes and other restrictions. The English government forbade the colonists to economically exploit the new territories that England won from France and Spain i.e. Canada and Louisiana..Additional taxation on a number of products).3) The colonist bourgeoisie strengthened4) Enlightenment (Freedom of thought, expression, economic liberalism)5) Rivalry of France, England (the French help the revolutionaries).

- THE EVENTS DURING THE REVOLUTION

1) 1773: Riots in Boston2) 1774: Representatives of the thirteen colonies gathered in Philadelphia and sent the King of England a declaration of rights.3) July 4, 1776: The Philadelphia convention passes the Declaration of Independence based on the political ideas of the Enlightenment. Protagonists in drafting the Declaration were Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson.4) September 1783: Treaty of Versailles: Complete independence of the 13 colonies.5) 1787: The Constitutional Congress succeeds in bringing together the two opposing tendencies in the assembly (strong central authority - autonomy of each state) and passes the United States Constitution.

The War of Independence lasted seven years and was initially very difficult for the disorganized colonial army.

-THE REVOLUTIONARY VICTORY

In the end, the Americans won thanks to:

1) The abilities of General George Washington.

2) The attitude of France that declared war against England.

3) The declaration of war by Holland and Spain against England.

4) The attitude of Russia, Denmark and Sweden which denied England the right to inspect the ships of neutral countries for enemy cargo.

- THE MILITARY STRUGGLE

From the War in the North (1775 - 1780)

1) Campaign in Boston, Massachusetts in 1775

- THE MILITARY STRUGGLE

From the War in the North (1775 - 1780)

1) Campaign in Boston, Massachusetts in 1775

2) Invasion of Canada: Quebec 1775

3) Campaign in New York and New Jersey in 17764) Battles of Saratoga and Philadelphia in 1777

- THE RESULTS AND CONSEQUENCES OF THE REVOLUTION

A. Constitution - Presidential Democracy

1) A Federal central government responsible for foreign policy, defense and finance.2) Each state retains legislative and executive authority over local government, police, justice and education.3) Legislative power is vested in Congress, which consists of the House and the Senate.4) Each state is represented in Parliament by a number of representatives proportional to its population. 5) Each state is represented in the Senate by two representatives regardless of its population.6) Executive power is exercised by the President who is elected by voters for four years and has the right to be re-elected once more. George Washington was elected the first president of the United States.7) The Judiciary headed by the Supreme Court is independent.

B. The national particularities of the colonists were set aside and thus not only a new state but also a new nation was created.

C. The American revolution was the first example of a successful outcome of a revolution that was followed by the Spanish colonies in Latin America but also states in Europe such as Switzerland, the Netherlands, Belgium and of course France.

D. The new state developed very rapidly in all areas and developed into a great power.

- THE FINANCIAL SITUATION IN THE REVOLUTION AND THE BANKING POLICY

But let's see in more detail how the Bank of England influenced the British economy and how, later, it was the one that caused the American Revolution. In the middle of the 18th century the British Empire was approaching the height of its power throughout the world. Britain since the creation of the central private Bank of England had participated in four wars in Europe. The cost was high though.

The British Parliament to finance these wars instead of issuing its own debt free currency borrowed huge sums from the bank. At that time the debt of the British government reached the exorbitant sum of £140,000,000. The government was therefore forced to vote on a scheme to raise public revenue, through the American colonies, to be able to pay the interest, at least, on the loans to the bank. In America the situation was different.

The heyday of a private central bank had not yet arrived, although the Bank of England had made efforts to impose its pernicious influence on the American colonies since 1694. Four years earlier, in 1690, the colony of Massachusetts had issued its own paper money. , the first in America. It was followed by the colony of South Carolina in 1703 and shortly thereafter by the rest of the colonies.

In the mid-18th century, pre-revolutionary America was still relatively poor. There was a serious shortage of gold and silver coins that could be used in trade and the purchase of goods, so that the early colonists were forced to experiment by issuing their own local paper money. Some attempts were successful. Also in some colonies they successfully used tobacco as a medium of trade.

In 1720 every colonial Royal Governor was ordered, usually unsuccessfully, to curtail the issue of colonial currency. In 1742 the British Resumption Act, which required payment of taxes and other debts in gold, caused an economic depression in the colonies, many properties were seized or confiscated from the rich for a tenth of their value. Benjamin Franklin was one of the biggest supporters of issuing colonial currency. In 1757 Franklin was sent to London to advocate for colonial currency.

He ended up staying eighteen years, almost until the start of the American Revolution. During this period most American colonies ignored Parliament and began issuing their own currency called "Colonial scrip". The effort was successful but had notable exceptions. Colonial currency provided a reliable medium of exchange and helped create a sense of unity among the colonies.

Let us remember that most colonial currencies were merely paper but debt-free currency issued in the public interest and not backed by gold and silver reserves. In other words it was "real money". Bank of England officials asked Franklin how he could explain the recent economic boom in the colonies. Without hesitation he answered them:

It is simple, in the colonies we issue our own currency called "Colonial Wallet". We issue the due ratio required by trade and industry to enable a comfortable exchange of products between the producer and the consumer. In this way we create for ourselves, our own currency, we control its purchasing power and we do not have to pay any interest. This was common sense to Franklin. But can you imagine the impact it had on the Bank of England?

America had discovered the secret of money and this genie needed to go back into its bottle as soon as possible. As a result, Parliament quickly passed the Currency Act of 1764, which prohibited colonial officials from issuing their own currency and ordered them to pay all future taxes in gold or silver coins. In other words, it obliged the colonies to join the gold and silver standard.

Thus began the first fierce act of the First Banking War in America, which ended with the defeat of the Moneylenders. A defeat caused by the Declaration of Independence and the subsequent peace agreement, the Treaty of Paris of 1783. Those who believe that a gold standard is the solution to America's modern monetary problems should look at what happened then, immediately after it was passed Currency Act of 1764. Franklin in his autobiography notes:

Within a year we found ourselves in the reverse situation, which marked the end of economic prosperity and the beginning of a deep and widespread economic depression, which drove armies of the unemployed into the streets of the colonies. Franklin is sure that this was the main cause of the American revolution. As he writes in his autobiography: The Colonies would gladly have accepted a small tax on tea and other products if England had not forbidden them to issue their paper money which created unemployment and discontent.

In 1774 Parliament passed the Stamp Act which required a stamp to be affixed to every article of trade as proof of payment of the tax in gold, which once again threatened the existence of colonial paper money. In less than two weeks the Massachusetts Committee of Safety passed a resolution ordering the issuance of more colonial paper money and accepting the coins of the other colonies.

On June 10 and 22, 1775, the Congress of the Colonies resolved by resolutions to issue $2,000,000 in return for the commercial and political loyalty of the "United Colonies". This constituted an act of defiance towards England, a refusal to accept a monetary system that was unfair to the citizens of the colonies. For this reason, the objects of commercial credit (bills of credit), i.e. paper money, which historians out of ignorance and prejudice have underestimated as objects of risky economic policy, were really the cause and occasion for the Revolution.

And it was much more than that, it was the Revolution itself. By the time the first shots were fired in Concord and Lexington, Massachusetts on April 19, 1775, the colonies were drained of gold and silver coins due to British taxation, leaving the continental government with no choice but to issue the its own paper money to finance the war. At the beginning of the revolution the American colonial money supply reached $12,000,000. By the end of the war it was close to $500,000,000.

In part this was due to mass counterfeiting by the British. But it had the effect that the money had essentially become worthless. The shoes sold for $5,000 a pair. As George Washington complained: A wagon full of money would scarcely buy a wagon full of supplies for the army. Earlier the colonial currency system was successful because only what was necessary to facilitate trade was issued and counterfeiting was minimal.

Today those who support a currency based on the gold standard focus on this period, during the revolution, to demonstrate the evils of "real paper money". But remember that the same currency had worked so well for twenty years, during peacetime, that the Bank of England asked Parliament to declare it illegal. Also during the war the British deliberately attempted to erode it by counterfeiting it in England and shipping it "by the pound" to the colonies.

- The Bank of North America

Toward the end of the revolution the Continental Congress met in Independence Hall in Philadelphia frantically trying to raise money. In 1781 he allowed Robert Morris, Treasurer of the Treasury, to establish a private central bank in the hope that they would succeed. Incidentally Morris was a financially well-to-do man who had become wealthy during the Revolution trading in war supplies.

The new bank, the Bank of North America as it was called, was modeled after the Bank of England. It was allowed, or rather not prohibited, to operate with minimal cash reserves, that is, to lend money it did not have and charge interest on it. If you or I did that we would be convicted of fraud, which is a felony. Few were aware of this practice at the time and of course it was kept secret from the people and politicians as much as possible.

Moreover, the bank was given the monopoly of issuing banknotes, which were also accepted in payment of taxes. The bank's charter invited private investors to participate in the initial capital of $400,000. But when Morris couldn't raise the money, he shamelessly used his political influence to have gold deposited in the bank, gold that France had lent to America. He then lent that money to himself and his friends to reinvest in the bank's stock.

The Second American Banking War had already begun. Soon the danger was clear. The value of the US currency continued to plummet. Four years later, in 1785, the contract with the bank was not renewed, effectively eliminating the threat from the bank's power. Thus the Second American Banking War ended very quickly with the defeat of the Moneylenders. The leader of the successful effort to close the bank was a patriot named William Findlay of Pennsylvania.

He explained the problem in the following way: This institution having no other priority than avarice will never diverge from its object...to monopolize all the wealth, power, and influence of the state. The plutocracy once established will corrupt the legislature so that laws are made in its favor and the Department of Justice will favor the rich. But the people behind the Bank of North America—Alexander Hamilton, Robert Morris, and the bank's president, Thomas Willing—didn't give up.

Only six years later, Hamilton, then Secretary of the Treasury, and his mentor Morris created a new private central bank, the First Bank of the United States, through the new Congress. Thomas Willing again served as the bank's president. The players were the same, just her name? bank had changed.

- The Constituent Assembly

In 1787 the leaders of the colonies gathered in Philadelphia to replace and amend the problematic articles of the "Charter of the Union". As we predicted, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, both unconvinced, opposed the creation of a private central bank because they saw the problems created by the Bank of England. They wanted none of that, and as Jefferson later put it:

If the American people ever allow private banks to control the issuance of their currency, first by inflation and then by deflation, the banks and businesses that will grow around these will deprive the people of their property until their children wake up homeless on a continent conquered by their fathers.

During the public debate over the future monetary system, another of the founders of the United States, Governor Morris, headed the committee that drew up the final draft of the Constitution and was well aware of the bankers' motives.

Along with his old boss, Robert Morris and Alexander Hamilton, they had presented the original plan for the Bank of North America to the Continental Congress during the last year of the Revolution.

In a letter he wrote to James Madison on July 2, 1787, he revealed what was really going on. The rich will fight for the prevalence of their sovereignty and the exandrapodism of the rest. This is how they always do and this is how they want it to be... The result here will be the same as elsewhere if we do not keep them with the power of the government in their proper field of action. Despite the defection of Governor Morris from the bank faction, Hamilton, Robert Morris and Willing and their European supporters were not going to back down.

They succeeded in persuading most of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention not to authorize Congress to issue paper money. Most dealers were still reeling from the massive inflation caused by paper money during the Revolution. They had forgotten how well colonial paper money had worked before the war. But the Bank of England had not forgotten. The Moneymakers did not accept the possibility that America would issue its own paper money again.

Many believe that the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution, which reserved powers to the states not represented in the federal government, made the issuance of paper money by the federal government unconstitutional, since the power to issue paper money was not expressly stated as a power of the federal government by the Constitution. The Constitution remains silent on this point. However, the Constitution expressly forbids the States from issuing paper money.

Most of the congressmen intended the Constitution to be silent on this point so as not to give the federal government "absolute power" to issue paper money. Indeed in the paper of the Assembly, on the sheet of August 16th, we read the following: The deletion of the words "prohibition of bank notes" was seconded, and the motion passed in the affirmative.

Hamilton and his banker friends saw this silence as an opportunity to keep the government out of issuing paper money, which they hoped to monopolize themselves. Thus the bankers and agents who were against them, each for different motives on his part, argued to leave the right of the federal government to issue paper currency outside the provisions of the Constitution, by a majority of four to one. This challenge opened the way for the Silversmiths, just as they had planned.

Of course the paper money itself was not the main problem. Lending with minimal reserves was a bigger problem because it multiplied any rate of inflation caused by excessive paper money issuance several times over. So the delegates were left with the thought that banning paper money was a good idea. By banning any kind of paper money they would probably also limit the minimum reserve banking that was practiced, as the use of checks was negligible and if it had been brought up for discussion would it have been banned as well?

Bank loans created by accounting entries in the books were not reported and thus not prohibited. It was thus considered that the issuance of paper money by the Federal and State governments was prohibited while the same was not meant for banks. It is disputed that this power of who has the right to issue by not being expressly prohibited to the government was reserved as a future right of citizens and the people (including legal entities such as banks).

An opposing view said that the banking companies were organs and agents of the states, since they recognized their legitimacy, and thus were not subject to the ban on issuing bank notes, as was the case for the states themselves. This argument was ignored by the bankers who proceeded to issue bank notes against minimum reserves and lost all ground when the US Supreme Court ruled that the federal government could establish a bank that could issue money.

Ultimately only the States were banned from issuing paper currency, and this ban was not imposed not only on banks but not even on municipalities and communities (as was the case during the 1929 economic depression in four hundred cities throughout the US).

Another mistake that is not often noticed has to do with the power given to the Federal Government to "mint currency" and "fix its value there and then".

Determining the value of the coin (i.e. its purchasing power or its value relative to other things) is not related to its quality or content (eg so many grams of gold and so many copper etc.) but to the quantity, the stock of money. It is the quantity that determines the value, and Congress has never legislated to set a specific quantity of money in the US. Legislating a specific amount of money (including coins, checks, and bank reserves) means in practice determining the value of each dollar (purchasing power).

A legislative act that defines the rate of increase of the money stock implies the determination of its future value. Congress has decided neither, although it clearly has the constitutional right to do so. He has relinquished that power to the Federal Reserve and the 10,000-plus banks that create our monetary reserve.

- INDEPENDENCE AND NEW STATE

England was forced to recognize the 13 colonies in the Treaty of Paris in 1783 as an independent state under the name of the United States of America (USA). The US constitution, which was drawn up in 1787 and is still in effect today, declared the country a union (Confederation) of states and was based on the principle of separation of powers. The central government decides on the economy, defense and foreign policy.

The states themselves regulate matters of local government, justice, education and policing. Legislative power is exercised by Congress through the Senate and the House of Representatives. Each state is represented in the Senate by two senators, regardless of its population. In the House of Representatives, however, the states are represented by a number of deputies proportional to their population.

Executive power is exercised by the President, who is elected every four years by an electorate and can be re-elected only once. The first president of the USA was elected, in 1789, George Washington. In his honor the US capital was later named after him. Finally, the judiciary was defined as independent and elected.

- KEY TO THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

The American Revolution (1775 - 1783) against the British had begun before the "unanimous declaration of the 13 United States of America" on July 4, 1776, which has been celebrated every year since then as US Independence Day. At first it was a struggle between Great Britain and its thirteen colonies in America, which opposed British legislation and sought their independence.

But it was also a struggle between the colonists as several Americans, mainly from England, who were called Loyalists (Law-abiding) or Tories (after the English Conservatives), sided with Great Britain against the colonial rebels. The American Revolution was still a continuation of the colonial wars between France and England. The French supported, first secretly and then openly, the American patriots.

The French Minister of Foreign Affairs of the monarchist government, Count Verzine, made sure to send munitions to the American revolutionaries, which were of particular importance as the rebels had no artillery and mainly lacked gunpowder. When the colonies proved their fighting ability, France recognized their independence, signed a treaty of alliance with them, and in 1778 entered the war on the side of the Americans.

One of the American patriots, the publicist Thomas Paine, whose book captivated North American revolutionaries, expressed views very similar to those of Riga the Bold and the French revolutionaries or philosophers. Paine wrote that "society is a great good, but power, in whatever form, is an evil. An honest man alone is more valuable than all the crowned rascals of the world. On the other hand, it is absurd for someone to claim that an island (Britain) can indefinitely dominate an entire continent."

The French and American revolutions set a positive precedent for enslaved Greece. And of course the political rights and freedoms provided for in the Regime of Riga Feraios, as in the first Greek constitutions, are borrowed from the "Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of the French Revolution".

- DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE OF THE USA

- THE INDEPENDENCE OF THE USA

From the beginning of the 17th century, the east coast of North America began to be steadily colonized by Europeans, mainly of British, Dutch, German and French descent. In the same context, the establishment of colonies also began, with the result that by 1732 13 colonies had been formed. The economy of these colonies was basically agricultural with vast arable lands.

Of course, while in the poorer South the pillar of the economy was the plantations of rice, corn, cotton and tobacco, in the developed North trade through maritime communications and with centers in the ports of New York, Boston and Philadelphia dominated. However, a point of friction between metropolitan England and the developing American region was the taxation policy of the former.