The most important battle in world history

The Battle of Plataea 479 BC it is one of the most important battles in world history, because it equalized the dominance of Europe.

-Until then, the huge Pesrian empire conquered one by one all the states of the then known world and there was no chance for anyone to resist them.

-However, with the Union of the army of the Greek Cities, he created a huge defensive army of 38000 men, and thus the united Greek army was able to fight and crush the huge Persian army. Thus the Greeks became the shield of protection for all of Europe

The Persian army was invincible until then and consisted of 110,000 selected men, the best army of the vast Persian empire.

The Persian army at Plataea

-------------------------------------------

Persians (the best chosen soldiers): 40,000

Meadows: 20,000

Bactrians, Indians, Sakas: 20,000

Asiatic Greeks and Macedonians who had grazed: 50,000

Total: 110,000 ( Best paid world soldiers )

All these groups provided cavalry, creating a combined force of about 5,000 horsemen.

The Greek army in Plataea

-------------------------------------------

Athenians - Αθηναίοι : 8,000

Corinthians - Κορίνθιοι : 5,000

Lacedaemonians - Λακεδαιμόνιοι : 5,000

Spartans - Σπαρτιάτες : 5,000

Megarites - Μεγαρίτες : 3,000

Sikyonians - Σικυώνιοι : 3,000

Tegeates Τεγεάτες : 1,500

Fleissians - Φλειάσιοι : 1,000

Threezinioi Τροιζήνιοι : 1,000

Anaktorioi / Lefkadis - Ανακτόριοι/Λευκάδιο : 800

Epidaurians - Επιδαύριοι : 800

Orchomenians - Ορχομένιοι : 600

Plataeus - Πλαταιείς : 600

Aeginites - Αιγινίτες : 500

Ambrakiotes - Αμπρακιώτες : 500

Eretrei/Styrei - Ερετριείς/Στυρείς : 600

Chalkideis - Χαλκιδείς : 400

Mycenaeans/Tyrynthians: 400

Ermioneis - Ερμιονείς : 300

Potidaiates - Ποτιδαιάτες : 300

Lepreates Λεπρεάτες : 200

Plateis Πλατείς: 200

Thespians Θεσπιείς: αδιευκρίνιστο : unspecified

Total: 38,700 ( Greek soldiers ready to die )

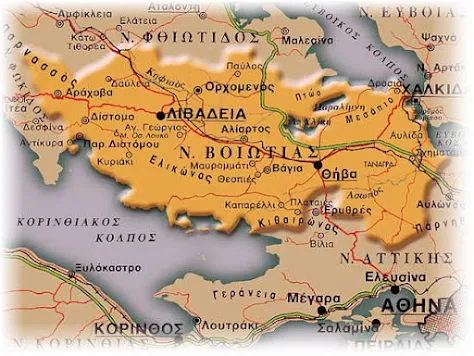

The Battle of Plataea 479 BC was the last battle on the land front during the second campaign of the Persians in Greece. It was held in August in Plataia of Viotia. The opponents in the battle were the Greek city-states (Sparta, Athens, Corinth and Megara) and Persia of Xerxes I. 479 BC. In the previous year, the Persian campaign in Greece had achieved significant successes at the Battle of Thermopylae and the naval battle at Artemisium, and Thessaly, Boeotia and Attica were captured. But, the victory of the Greeks in the naval battle of Salamis prevented the capture of the Peloponnese by the Persians. Xerxes retreated with much of his army and left his general, Mardonius, to fight the Greeks the following year.

After his defeat in the naval battle of Salamis, Xerxes, leaving Mardonius in Thessaly, left for Persia. Mardonius tried to negotiate with the Athenians, offering them to ally with him with various exchanges. But the Athenians proudly refused, so Mardonius with his 300,000 soldiers encamped in the valley of Asopos, near Plataeus.

Mardonius, before invading the south, tried to detach the Athenians from the Greek alliance by sending as an ambassador the king of Macedonia, Alexander, who promised to compensate for the damages and offer any help if they allied with the Persians. When the Spartans learned about this embassy they were afraid because they knew that Attica had been deserted and the Athenians were facing the specter of starvation and they were also unhappy because the Peloponnesians had not sent an army in time to Boeotia as they had promised to protect their city. Therefore they hastened to send ambassadors to prevent the capitulation, promising that they and the rest of the allies would undertake to feed the families of the Athenians.

After his defeat in the naval battle of Salamis, Xerxes, leaving Mardonius in Thessaly, left for Persia. Mardonius tried to negotiate with the Athenians, offering them to ally with him with various exchanges. But the Athenians proudly refused, so Mardonius with his 300,000 soldiers encamped in the valley of Asopos, near Plataeus.

Mardonius, before invading the south, tried to detach the Athenians from the Greek alliance by sending as an ambassador the king of Macedonia, Alexander, who promised to compensate for the damages and offer any help if they allied with the Persians. When the Spartans learned about this embassy they were afraid because they knew that Attica had been deserted and the Athenians were facing the specter of starvation and they were also unhappy because the Peloponnesians had not sent an army in time to Boeotia as they had promised to protect their city. Therefore they hastened to send ambassadors to prevent the capitulation, promising that they and the rest of the allies would undertake to feed the families of the Athenians.

The Athenians were also waiting for the ambassadors of Sparta to answer in front of them the envoy of Mardonius and after hearing the words of both of them they replied to Mardonius through Aristides "that as long as the sun does not change its course they are not going to capitulate with Xerxes but remaining loyal to the gods and heroes he burned their temples and statues will persist in fighting for their freedom." The Spartans were told that they thanked them for the proposal but that they would manage on their own and all they asked was to send the fastest army to Boeotia to join the Athenian and fight.

The Spartans, however, once again broke their word by not sending an army to Boeotia but staying in their homeland to celebrate Hyacinthia. The result was that Mardonius passed from Thessaly to Attica unhindered, having with him as allies all the nations of eastern Greece, forcing the Athenians for the second time not being able to face such a numerous army leave their city and go to Salamis.

There Mardonius sent a second embassy to the Athenians to repeat the previous proposals. The new disloyalty of the Spartans had sharpened spirits nevertheless when the proposals were announced to the parliament, all the deputies except one named Lycides, rejected the Persian proposals and stoned the deputy and his family to death. The Athenians sent ambassadors to Sparta together with the Megarians and Plataeans to protest against this new breach and to demand the immediate dispatch of an army if not to Boeotia which had been occupied by the enemy in the Thriasian field.

There Mardonius sent a second embassy to the Athenians to repeat the previous proposals. The new disloyalty of the Spartans had sharpened spirits nevertheless when the proposals were announced to the parliament, all the deputies except one named Lycides, rejected the Persian proposals and stoned the deputy and his family to death. The Athenians sent ambassadors to Sparta together with the Megarians and Plataeans to protest against this new breach and to demand the immediate dispatch of an army if not to Boeotia which had been occupied by the enemy in the Thriasian field.

The Spartan prefects after hearing the embassy said they would think about it and reply instead they delayed 10 days postponing the reply continuing to celebrate the Hyacinths and fortify the isthmus. Thus, after the Athenian ambassadors were upset, they told them that if they did not receive an answer the next day, they would ally themselves with Persia. The governors fearing this outcome informed the Athenians that the army had already started and was at this time outside the borders of Sparta, 5000 Spartans each followed by 7 lightly armed helots. The example of the Spartans was followed by other Peloponnesians so that a significant force left the Peloponnese led by Pausanias the commissioner of the minor king Pleistarchus son of the dead king Leonidas. Mardonius, having been notified by the Argives of the movements of the Peloponnesian army, retreated after plundering the region of Tatio which he had respected in the hope of the capitulation of the Athenians to Boeotia, and encamped on the plain in front of the walled city of his Theban allies in order to cover his back and to be able to compete in an open space.

After the glorious victory of the Greeks at the Straits of Salamis, the winter of 480/479 BC imposed a suspension of operations and limited the opponents to reconnaissance and diplomatic movements. The news of the victory of the allied Greeks at Salamis traveled quickly throughout the Greek world, spreading excitement. So let's see what happens during this time until the summer of 479 BC.

Persians

After the departure of Xerxes from Greece, the rescued Persian fleet gathered at Kymi in Asia Minor where it spent its winter. Some Persian ships with Medes and Persians (army-marines) passengers, spent the winter in the port of Samos (today's Pythagorion) in order to be able to intervene immediately in case of a revolt of the Ionian cities.

When spring came all the Persian ships, 300 in all, assembled at Samos under the command of the generals Mardontis and Artauntis. Because of the severe trial they had undergone they did not

SAMOS AND CHERSON. MYKALIS

proceeded westward and limited themselves to staying in Samos and guarding Ionia so that it would not defect. Nor did they expect that the Greeks would come to Ionia, believing that they would be content to guard their homeland. This they inferred from the fact that the Greek fleet did not pursue them when they left Salamis.

From the sea struggle, they were very disappointed and had high hopes that Mardonius in the land operations would defeat the Greeks. Remaining in Samos on the one hand they intended to cause harm to their enemies and on the other hand they were awaiting the result of Mardonius' actions.

Mardonius spent the winter in Thessaly and when spring came he sent a man, Myn from the city of Europa in Caria, to all the oracles in the area to receive oracles. and that of Amfiaraou in Oropos, Attica. Herodotus gives no details of these oracles, nor what oracles he received.

Mardonius spent the winter in Thessaly and when spring came he sent a man, Myn from the city of Europa in Caria, to all the oracles in the area to receive oracles. and that of Amfiaraou in Oropos, Attica. Herodotus gives no details of these oracles, nor what oracles he received.

After Mardonius had studied the oracles, he sent to Athens as an ambassador, the Macedonian king Alexander I Amyntas, who on the one hand was related to the Persians (his sister had married a noble Persian) and on the other had served as consul and benefactor of the Athenians. The consuls received the ambassadors of the states they represented (in this case Macedonia) and introduced them to the municipal church (parliament) and generally looked after the interests of their state.

By this action, Mardonius hoped that he would more easily join the Athenians, of whom he had heard that they were a numerous and brave people, and he also knew that they more than all had caused the Persians to suffer the recent calamities at sea. So if he took them with him, he had hope of easily prevailing at sea as well. On land he thought he was far superior. In this way he calculated to gain supremacy over the Greeks.

However, it is also possible that the recent oracles he received told him what would happen and advised him to ally with the Athenians. So, complying with the oracles, he sent King Alexander to Athens.

Greeks

The coming of spring and the presence of Mardonius in Thessaly brought the Greeks together again. Before the land army was even assembled, the Greek navy consisting of 110 triremes assembled at Aegina. The admiral of the Athenian fleet was the general Xanthippos of Ariphron (father of the well-known Pericles) and of the Spartan, but also of the entire fleet, the king of Sparta Leotychides of Menareus. The Athenians assigned the command of the land army to the general Aristides the Fair.

By this action, Mardonius hoped that he would more easily join the Athenians, of whom he had heard that they were a numerous and brave people, and he also knew that they more than all had caused the Persians to suffer the recent calamities at sea. So if he took them with him, he had hope of easily prevailing at sea as well. On land he thought he was far superior. In this way he calculated to gain supremacy over the Greeks.

However, it is also possible that the recent oracles he received told him what would happen and advised him to ally with the Athenians. So, complying with the oracles, he sent King Alexander to Athens.

Greeks

The coming of spring and the presence of Mardonius in Thessaly brought the Greeks together again. Before the land army was even assembled, the Greek navy consisting of 110 triremes assembled at Aegina. The admiral of the Athenian fleet was the general Xanthippos of Ariphron (father of the well-known Pericles) and of the Spartan, but also of the entire fleet, the king of Sparta Leotychides of Menareus. The Athenians assigned the command of the land army to the general Aristides the Fair.

The winner of Salamis, Themistocles, was probably sidelined and many assume that he did not succeed in the mission assigned to him when he went to Sparta, because he did not get a positive response to the Athenian demands. So it seems that this attitude of the Spartans created some discontent inside Athens and as far as Themistocles himself is concerned, a popular antipathy toward him gradually began to grow, as Plutarch tells us (Plut.Themis.22), but also generally about the policy that the Athenians were to follow henceforth.

XANTHIPPOS

The fact becomes even more paradoxical if it is combined with a similar change in Sparta, where one of the two kings, Leotychides, took over as admiral of the Spartan, but also of the entire Greek fleet in place of Eurybiades. Thus the two men who led the Greek triremes to the triumph of Salamis, after being honored for their services, were set aside

ARISTEIDES THE RIGHTEOUS

Moreover, let us remember the auspicious collaboration of Themistocles and Eurybiades. Their removal, about which the ancient sources keep absolute silence, justifiably raises many questions. The growing envy of the Athenians for the glory of Themistocles is sufficient reason to interpret his marginalization. On the other hand, the great influence, evident to many, which Themistocles proved to have had on the decisions of the admiral Eurybiades, was probably the reason for the replacement of the latter by Leotychides. Probably the prefects and senate of Sparta resented this influence of the Athenian general over one of their own as dangerous. But there were also changes in the leadership of the Spartan land army.

Cleombrotos, regent and commissioner of king Pleistarchus, his minor son Leonidas, commander-in-chief of the Peloponnesians on the Isthmus, died in Sparta at the end of October 480 BC. In his place was placed Pausanias, the son of Cleombrotos, whom he chose as vice-leader

Samos seemed to them to be as far away as the Heraklion columns (today's Gibraltar). So the barbarians did not dare to sail west of Samos and the Greeks east of Delos, despite the pleas of Chios. The space between the two opponents was kept by "fear" !!!

The envoy of Mardonius, the king of Macedonia, Alexander I, arrived in Athens and announced to the Athenians the tempting proposals of the Persian general. According to them, the Persians would forgive the Athenians for their old "mistakes", grant them large territories, compensate them for the damages and rebuild the temples they had burned, if they agreed to become allies of the Persian monarch. The Athenians indignantly rejected the proposals. On the same day that Alexander the First presented himself in the Church of the Municipality, Spartan ambassadors also arrived. Thus the Athenians listened successively to the proposals of Alexander and to the arguments of the Spartans, who were anxious lest the Athenians should yield. The Athenians, however, gave two proud answers:

PAUSANIAS

his cousin Euryanacts, the son of Dorieus, another brother of Leonidas. Here we should note that the general Cleombrotos, brother of Leonidas, withdrew from the Isthmus, in October 480 BC, the army since during a sacrifice for the war against the Persians, the sun darkened and issued this as an ominous sign. It was a partial eclipse of the sun. When the Greek ships gathered at Aegina, Chios arrived as ambassadors of the Ionians to the camp of the Greeks, who had first visited Sparta and begged the Lacedaemonians to liberate Ionia. There were seven of them and they had agreed to exterminate the tyrant of Chios, Stratinus. But when one of them revealed their plans, they escaped from Chios and went to Sparta and then to Aegina and begged the Greeks to sail to Ionia. But the only thing they managed was to bring the Greek fleet to Delos. Beyond Delos, however, the Greeks were afraid to advance because they did not know what was happening and believed that the entire area east of Delos was full of enemy troops. LOCATION N.DILOS

The envoy of Mardonius, the king of Macedonia, Alexander I, arrived in Athens and announced to the Athenians the tempting proposals of the Persian general. According to them, the Persians would forgive the Athenians for their old "mistakes", grant them large territories, compensate them for the damages and rebuild the temples they had burned, if they agreed to become allies of the Persian monarch. The Athenians indignantly rejected the proposals. On the same day that Alexander the First presented himself in the Church of the Municipality, Spartan ambassadors also arrived. Thus the Athenians listened successively to the proposals of Alexander and to the arguments of the Spartans, who were anxious lest the Athenians should yield. The Athenians, however, gave two proud answers:

To Alexander they said:

"We know that the Persians have troops many times more than ours, but as we love liberty too much, we will defend it as long as we can. So convey to Mardonius that the Athenians say that as long as the sun follows the straight path, which he follows even now, we will never make an alliance with Xerxes, but trusting in our allied gods and heroes, whose temples and statues he burned without respect, we will campaign against him and repel them".

To the Spartans, who had begged the Athenians not to accept the proposals of Mardonius and that they would take care to feed during the war the women, children and helpless Athenians, they replied:

"There is nowhere on earth so much gold or country so superior in beauty and wealth, that we should accept them and want to enslave Greece. Many and great are the causes, which, even if we wanted, prevent us from doing such an act. First of all, the statues and the burned ones destroyed temples of the gods, for which we seek revenge and not to ally with the cause of this destruction. Besides, the Greeks all have the same blood and the same language, common temples and sacrifices, common customs. Let the Athenians become traitors to all of them it is not right".

They then thanked the Spartans for the proposals to feed the Athenian families and urged them to immediately send an army, because surely after the rejection of the proposals Mardonius will invade Attica. So before this happens the Athenians will march to Boeotia and wait for him there. After receiving the Athenians' answer, the Spartan ambassadors returned to their country.

"We know that the Persians have troops many times more than ours, but as we love liberty too much, we will defend it as long as we can. So convey to Mardonius that the Athenians say that as long as the sun follows the straight path, which he follows even now, we will never make an alliance with Xerxes, but trusting in our allied gods and heroes, whose temples and statues he burned without respect, we will campaign against him and repel them".

To the Spartans, who had begged the Athenians not to accept the proposals of Mardonius and that they would take care to feed during the war the women, children and helpless Athenians, they replied:

"There is nowhere on earth so much gold or country so superior in beauty and wealth, that we should accept them and want to enslave Greece. Many and great are the causes, which, even if we wanted, prevent us from doing such an act. First of all, the statues and the burned ones destroyed temples of the gods, for which we seek revenge and not to ally with the cause of this destruction. Besides, the Greeks all have the same blood and the same language, common temples and sacrifices, common customs. Let the Athenians become traitors to all of them it is not right".

They then thanked the Spartans for the proposals to feed the Athenian families and urged them to immediately send an army, because surely after the rejection of the proposals Mardonius will invade Attica. So before this happens the Athenians will march to Boeotia and wait for him there. After receiving the Athenians' answer, the Spartan ambassadors returned to their country.

The Battle of Plataea 479 BC (3D Animated Documentary) Greco-Persian wars

As soon as Alexander returned and reported on the Athenians' response, Mardonius hastily began to advance with his entire army towards Attica and forcibly recruited the inhabitants of the regions he passed through. The leaders of Thessaly agreed to this, who did not repent of their anti-Hellenic actions until then, but were inciting Mardonius much more now.

So at the end of the spring of 479 BC. Mardonius proceeded to Boeotia and there completed the preparations for supply and encampment. The Thebans,

wishing to keep the Persians in Boeotia, advised Mardonius to remain there since there was no more suitable ground to encamp, and thus, remaining there, to act so as to occupy all of Greece without a fight. They also advised him to send money to the powerful of the Greek cities, so as to divide the Greeks and thus easily enslave them. Mardonius, however, was not offended and, because of his foolishness, ardently desired, on the one hand, to capture Athens for a second time and, on the other hand, to spread with torches from island to island to Xerxes who was in Sardis, the news of the capture of Athens. Also in this way to force the Peloponnesians to come out of the Isthmus and give battle with him in an open field

ATHENS 5th CENTURY BC

He immediately sent to the Athenians Hellespontius Murychidis, who appeared in the Parliament of 500, which as an exile was based in Salamis, the only free part of the Athenian state. The proposals that Murychidis made to the Athenian parliamentarians were the same as those presented by Alexander. For the majority of the Athenian parliamentarians, there was no point in any debate, especially under the weight of the brutal blackmail and psychological pressure that the occupation of their state entailed.

The irritation of the Athenians was justifiably very great and, as they were "in a boiling state of soul", they could not stand even one of the deputies, Lykides, who dared to suggest that it was in their interest to approve the proposals of Mardonius and lead them in a vote in the "Municipal Church", he was executed by stoning. When the women of the Athenians heard about Lycides, urging each other on, they rushed to his house and stoned his wife and children to death. They didn't bother Mourichidis and let him go.

THE ATTITUDE OF SPARTA

The Athenians felt disappointed by the attitude of the Lacedaemonians who had not yet come with their army, according to the condition they had set upon them when they refused the proposals of Mardonius. Instead, the Lacedaemonians, after their allies the Peloponnesians, again crossed the Isthmus and continued the construction of the wall, being at the point where the ramparts were erected. Following Aristides' proposal, the Athenians sent an embassy to Sparta by the generals Cimon, Xanthippos and Myronides from Plataea, who were accompanied by Megareans and Plataeans, on the one hand to express their grievances, because they had let Mardonius invade Attica and not they went to Boeotia with the Athenians to confront him, and on the other hand to remind them of the promises the Persians had made to them, if they had sided with them.

ANCIENT SPARTA

The ambassadors presented themselves to the prefects of Sparta accusing them of treachery, inconsistency and indolence and also pointed out to them that if they did not help the Athenians, then the Athenians themselves would see to their salvation.In those days the Spartans celebrated the "Hyacinthia" which was an annual holiday during the months of July and August, in honor of Apollo's friend, Hyacinthos. The magistrates listened to them calmly, and did not appear to be moved by the accusations made, and deferred their answer for ten days, telling them each day that they would answer the next. During this time of ten days they were trying to finish the wall on the Isthmus, working day and night, the erection of which was at an end. This seems to have been the reason for the constant postponements of the answer, since with the completion of the wall, they felt secure and believed, according to Herodotus, that they no longer needed the Athenians.

OFFICERS AND AMBASSADORS

The mobilization within a few hours of 45,000 men shows us the admirable mechanism of the Spartan state. The movement of the army during the night was probably done for reasons

SPARTANS

of security, in order not to be noticed by the Argives who were eavesdropping and alert the Persians. Nevertheless, the Argives were informed of the movement of the Spartan army and immediately sent their best postman to Athens who informed Mardonius about the events.THE ARRIVAL OF THE GREEKS IN THE SQUARES

SPARTANS

DIV. OAK HEADS (CASE)

Then, following the mountain passes of Kithairona that led to the fortress of Eleftheri (today's Gyftokastro), they passed through the passage of Dryos Kefalos (today's Kaza) and reached Erythres in Boeotia (near present-day Kriekouki or Erythres). Low in the depth of the plain they saw the Persians to wait for them. It was mid-August of 479 BC.

The Commander-in-Chief Pausanias, seeing the Persians arrayed north of the Asopos river, deployed his army along the foothills of Kithairon, south of the river and to the right of the exit of the Dryos Kephalos pass. The river Asopos crosses the Boeotian plain from west to east, almost parallel to Kithairon, and divides it into two parts, the southern one including the zone as far as Kithairon, which is interrupted by hills and ravines and is not suitable for the cavalry, and a northern part which extends to Thebes and is an extensive plain, suitable for cavalry.

FREEDOM FORTRESS (GYFTOKASTR)

The location of this starting line-up was chosen for several reasons. On the one hand it was necessary to control the passage because new units of the Greek army were constantly arriving and on the other hand the road had to remain open for resupply from Attica and southern Greece. Moreover, the position was favorable to defend the heavy Greek infantry, since the ravines and low hills made the terrain completely unsuitable for the easy deployment of the Persian cavalry.

The objective purpose of Mardoni was to fight on this plain. All the maneuvers and movements of the Greek army, until the moment the battle was fought, must have had the opposite objective, that is to force Mardonius to attack the area south of the Asopus river and especially the mountainous terrain of the lower part of Kithairon, in terrain, that is, completely unsuitable for Persian cavalry.

When the Greeks crossed Kithairon, the Persians had already organized their positions. Mardonius had placed outposts on a line running north of the Erythrae and the Plataea, while the main body of the army was encamped on the north bank of the Asopus, at a distance of eight kilometers from Thebes. In this line-up the Persians occupied the left wing, the "wandering Greeks" the right and the other Asiatic nations the centre. Behind this

faction was the wooden camp of Mardonius in which ramparts and towers had been built as well as a deep ditch that surrounded it (Diod.IA, 30). Mardonius, after occupying these positions, left the Greeks undisturbed for a while, probably in the hope that they would pass Asopus, to attack him on the open plain, where he had the advantage of strong cavalry.

FORCES OF THE OPPONENTS

Greeks

Heavily armed infantry: Lacedaemonians 10,000, Tegeans 1,500, Corinthians 5,000, Potideans 300, Orchomenians Arcadians 3,000, Epidaurians 800, Troizenians 1,000, Lepreates (Triapophylia) 200, Mycenaeans- Tiryns 300, Fleiasians 1000, Hermiones 300, Eretrias- Styrians 600, Chalcidians 500, Lefkadians-Anactorians 800, Pallinians (from Cephalonia) 200, Aeginites 3000. Plataeans 700, Athenians 8000, Thespians 2000. Total of heavily

armed hoplites .600.

Light-armed infantry: In the ranks of the Spartans 35,000 (seven to each hoplite) all trained for war. To the rest of the Lacedaemonians and Greeks 34,500. Total Psilos 69,400.

Total Greeks 110,000

Persians

Persians 20,000, Medes 15,000, Bactrians 30,000, Indians 10,000, Saxons 15,000, Greeks about 50,000 (Macedonians, Boeotians, Locrians, Malians, Thessalians, Phocians) among the Greeks, others had volunteered, such as Thessalians and Boeotians and others against their will, like the Macedonians of the

PERSIAN IMMORTALIANS

whose country had been occupied since 492 BC. Only 1000 of the Phocaeans had grazed, and the rest had fled to Parnassos and from there rushed to help the Greeks with small (rather raiding) attacks against the army of Mardonius and his Greek allies. Total 140,000.

But there were others more lightly armed, such as Phrygians, Thracians, Mysians, Paeonians, Ethiopians and Egyptians. It seems that Mardonius disembarked crews from the ships, while the barbarian fleet, which followed him, was still at Faliro. This shows that there were no Egyptians in the army that Xerxes led to Athens.

armed hoplites .600.

Light-armed infantry: In the ranks of the Spartans 35,000 (seven to each hoplite) all trained for war. To the rest of the Lacedaemonians and Greeks 34,500. Total Psilos 69,400.

Total Greeks 110,000

Persians

Persians 20,000, Medes 15,000, Bactrians 30,000, Indians 10,000, Saxons 15,000, Greeks about 50,000 (Macedonians, Boeotians, Locrians, Malians, Thessalians, Phocians) among the Greeks, others had volunteered, such as Thessalians and Boeotians and others against their will, like the Macedonians of the

PERSIAN IMMORTALIANS

whose country had been occupied since 492 BC. Only 1000 of the Phocaeans had grazed, and the rest had fled to Parnassos and from there rushed to help the Greeks with small (rather raiding) attacks against the army of Mardonius and his Greek allies. Total 140,000.

But there were others more lightly armed, such as Phrygians, Thracians, Mysians, Paeonians, Ethiopians and Egyptians. It seems that Mardonius disembarked crews from the ships, while the barbarian fleet, which followed him, was still at Faliro. This shows that there were no Egyptians in the army that Xerxes led to Athens.

Total of Mardonius' stactus about 300,000

THE OATH OF THE GREEKS AT PLATAIAS

The orator Lycurgus mentions that the following oath was taken at Plataia shortly before the battle and that it was an imitation of the oath that Athenian citizens took when they became teenagers and were registered at the registry office (Lycur. Kata Leokratous, 80).However, according to Diodorus (IA, 29) it was given by the Greeks who gathered on the Isthmus. Herodotus also refers to an oath taken by the Greeks, but Theopompus considers it illegitimate. In addition, in Acharnes (Menidi) there was a marble inscription with the famous Plataean oath, but it has been argued, rather convincingly, that it is a spurious historical text, one of those forged in the years following the Persian wars. The prevailing view among historians today is that an oath was probably given, probably on the Isthmus, but ultimately its core was altered by later additions.

THE OATH OF THE GREEKS AT PLATAIAS

The orator Lycurgus mentions that the following oath was taken at Plataia shortly before the battle and that it was an imitation of the oath that Athenian citizens took when they became teenagers and were registered at the registry office (Lycur. Kata Leokratous, 80).However, according to Diodorus (IA, 29) it was given by the Greeks who gathered on the Isthmus. Herodotus also refers to an oath taken by the Greeks, but Theopompus considers it illegitimate. In addition, in Acharnes (Menidi) there was a marble inscription with the famous Plataean oath, but it has been argued, rather convincingly, that it is a spurious historical text, one of those forged in the years following the Persian wars. The prevailing view among historians today is that an oath was probably given, probably on the Isthmus, but ultimately its core was altered by later additions.

I'M TALKING ABOUT HER LIFE NOWFREEDOM. I DON'T MISS THEMRULER NOR ALIVE NORDYING, BUT THEM IN FIGHTEND OF ALLIES EVERBURIED AND YOU KEEP THEIR WARNONE OF THE BARBARIANS AMONG THE CONTESTANTSOF CITIES, AND THEOF SAINTS OF THE INSANE ANDI DO NOT BUILD ANY PAYMENTS,ANOTHER MEMORIAL TO THE INSPIREDI AND I WILL OVERCOME THE BARBARIANSASSEVIAS. (Lykourgos, Kata Leokratou 81.)

"I will not esteem my life higher than liberty, nor will I forsake the chiefs, either living or dead, but such of the allies as have fallen on the field of battle, all without exception I will bury. And, if I vanquish the barbarians, I will not desolate none of the cities that fought. And of the sanctuaries that were set on fire and torn down by the barbarians, I will not rebuild anything at all, but will leave them to posterity as a memorial of the impiety of the barbarians."

The Greek army was late in reaching Eleusis because the Lacedaemonians had to wait for the other Peloponnesians. Finally, 1,500 Tegeans, 5,000 Corinthians, 300 Potidaeans, Corinthian settlers, 600 Orchomenian Arcadians, 3,000 Sikyonians, 800 Epidaurians, 1,000 Troizenians, 200 Lepraeans, 400 Mycenaeans and Tirynsians, 1,000 Phliasians, 300 Hermes arrived Ionians, 600 Eretrians and Styrians, 400 Chalkidians ,500 Ambrakiites, 800 Lefkadians, 200 Palles from Kefallinia and 500 Aeginites. When the army arrived at Megara, it was joined by 8000 Athenians and 600 Plataeans led by Aristides. If we add to these forces the 5000 Spartans who were followed by 3500 Helots and 1800 Thespians, the Greek army numbered 11000 men. From Eleusis, Pausanias passing through Boeotia saw the Persian army lined up at the Asopus river and not daring to descend to the plain. in order to confront the 300,000 men of the Persian army, he preferred to camp at the foot of the mountain.

Then Mardonius made the mistake of attacking the Greeks with his cavalry which was excellent and numerous and led by one of the best Persian officers, Masistios. The mistake was that the terrain being uneven did not lend itself to such an attack. Thus the Megarians who were attacked due to their position after being terribly pressed at the beginning, helped by 300 Athenians led by Olympiodorus, repelled the enemy

ASOPOS POT. TODAY

THE DEATH OF THE BROKER

Mardonius sent against them all his cavalry under the command of the illustrious Persian Masistius, who was riding a golden-briddled and brilliantly decorated Nessian horse. It remains unknown what Mardonius had in mind with this attack, which certainly, as Herodotus describes it, exceeds in the context of a bombing or reconnaissance operation. Perhaps it was an attempt to ascertain the capabilities of his cavalry on this ground, against the armored phalanx. Perhaps again he intended to draw the Greeks into ground generally more suitable for the Persian army. The Persian cavalry did not adopt the usual tactics, but charged head-on against the Greek horsemen, inflicting heavy casualties on them and hurling heavy abuse at them, mockingly calling them "women," for to the Persians there was no worse abuse than to call someone a coward. and by a woman.The Megarians were, according to Herodotus, placed in unsuitable ground for defense and suffered the main charge of the cavalry and a barrage of arrows and javelins. So they were forced to ask for reinforcements from Pausanias. The commander-in-chief called volunteers from the others

CAVALRY AGAINST HALLS

Greeks, but only 300 Athenian elite hoplites and archers showed up. In the long-hour battle that followed, the Athenians killed the leader of the Persian cavalry Masistios and captured his horse. The Persians tried to take Masistios' corpse and thus a fight became general and only when he reached the field the main body of the Greeks, the Persian cavalry withdrew. Thus the conflict probably ended with the victory of the Greeks.In Herodotus' narrative, the Athenians are presented as voluntarily rushing into the fray, while the other Greeks refused. It is natural to assume that the Athenians ran to help the Megarians, because they were closer to them and because they had archers. The battle seems to have been decided more by the superiority of the Greek hoplites in mountainous terrain. Mardonius was thus taught that he could not attack with the cavalry at this point, so he withdrew it and left the initiative of the movement to Pausanias, hoping, perhaps, that the Greeks would advance on the plain beyond Asopus. When the Persian horsemen returned to the camp without the corpse of Masistius, the whole army and Mardonius mourned for him, cutting off their heads and beards, shearing their horses and saddles, and uttering beautiful lamentations, the cry of which was heard throughout Boeotia. plain, because the dead man was considered by the Persians and Xerxes as the most prominent after Mardonius.

MASSISTIUS

The Greeks, after the repulse of the cavalry, took courage and after placing the dead man in a carriage, they took him around to all the divisions of the Greek army. Because the dead man, due to his size and his beauty, caused interest, the soldiers left their divisions and went to see the dead Masistios. The ancient Greeks were distinguished for their beauty, and this energy, the circumambulation of the dead, was also a "psychological operation" to boost the morale of the Greek fighters.

THE ALIGNMENT

OF THE GREEKS

After this first success, Pausanias decided to advance and bring his army's array closer to Plataea. The reasons that dictated this decision to him are certainly not known. He was certainly encouraged by the first success and faced with greater confidence in the possibility of fighting on flat terrain. At the same time, he hoped that he would more easily lure the Persians into a confrontation, now that he was in less mountainous terrain.

Finally, perhaps the lack of water forced him to change his position. Herodotus says that the Greek army marched westward along the foothills of Kythairon, past the Hysias, to the territory of the Plataea, and encamped by nations near the fountain Gargaphia (its location is not known today) and the sanctuary of the hero of Plataion Androkratis, which is six stadia (about 1200 m.) from Plataia, on uneven ground with low hills.

THE 2ND POSITION OF THE GREEKS

While the Greeks were preparing to line up in the new position, an argument broke out between the Athenians and Tegeans about who should be on the left wing. The Tegeans were said to be the most worthy allies of the Spartans and deserved that position. The Athenians replied that "the purpose of the campaign is to fight the barbarians and not to argue. But since you have raised this issue we answer you that since we always do the right thing, it is our paternal tradition to have the primaries". The final solution to the argument was given by the entire Lacedaemonian camp, which shouted that the Athenians were superior to the Arcadians and that the left wing belonged to them.

After that the Greek army lined up as follows:

The lateral move, probably carried out at night, to occupy the second position, is according to today's strategic understandings, quite unorthodox. In addition, it left a gap in front of the Persian line, as a result of which the crossing of Dryos Kefali, where the supply road of the Greek army passed, was exposed. The new position also had the disadvantage of leaving the Hellenic center exposed.

Pausanias might have been looking to provoke an attack by the strong Persian center at that point, so that the two ends (Lacedaemonians and Athenians) could attempt a circular movement, as in Marathon. The fact that Pausanias was later forced to change his position again proves the impossibility of this movement.

Persians

After the end of mourning in the camp of the barbarians, Mardonius, seeing the Greeks that they had descended lower, rejoiced. The tactic of waiting that he had implemented with the volleys of his cavalry, bore fruit as the opponent had moved to the exact point he wanted so that to be able to deploy the cavalry. So he lost no time and moved his troops westward along the north face of the Asopus River and arrayed them as follows:

WAITING BEFORE THE GREAT BATTLE

Both Mardonius and Pausanias each had their own reasons for not wanting to attack first. Although the Greeks had lined up in a vulnerable position, Mardonius did not seem eager to attack first, preferring instead to wait. the first move by the Greeks that would offer him a comparative advantage. He was smart enough not to underestimate the opponent and considered it too risky to attack him.

The unfortunate outcome of the attacks he had launched with his cavalry and the tragic end of Masistios had convinced him that great caution was required against the Greek phalangites. He had to face not only the best warriors, but also a considerable army, since the ratio of 1:3 (Greeks to Persians) left all possibilities open for the outcome of the battle. So Mardonius was determined to order an attack only when he was quite sure.

But Pausanias also decided that the Persians' defensive position was the most secure and advantageous, rather than crossing the Asopus, exposing the Greek infantry to the advances of the Persian cavalry.

Thus the two armies remained idle in their new positions for eight days, for the oracles, Tisamenus of the Greeks and Hegisstratus the Helios who was in the camp of the Persians, declared to both camps that the omens were good for defense, but not to attack after crossing the river.

On the ninth day, because new fighters were coming to the camp of the Greeks from everywhere, Mardonius, at the instigation of the Theban Timagenis, sent during the night some divisions of cavalry to the passes of Kithairon with a view to placing under his control the strait of the Dryos Kefalon (note Kaza), from where the supply convoys that supplied the Greek army passed. The Persian horsemen managed to block the passage and even capture a supply convoy with 500 ships carrying food from the Peloponnese, mercilessly slaughtering people and animals.

After the loss of the passage, Pausanias began to be pressed for time since he would soon have a problem of feeding his soldiers, but also of general supplies. The Greeks believed that the Persian attack was only a matter of time. But the wily Mardonius had an exasperating patience, and apart from the occasional skirmishes and harassing advances of the Persian cavalry, he did not seem inclined to attack first.

During the next two days neither opponent decided to attack. Mardonius

With these actions, on the one hand, they wanted to lure the Greeks into an attack north of Asopus, and on the other hand, with the suspicion of a Persian attack, they constantly kept the heavily armed Greeks in battle tension, causing irritation and fatigue. The strain of the Greek soldiers from the many days of waiting was certainly very great, if we take into account both the weather conditions (August with an average temperature of 32-34 °C) and the weight of their weapons (31 kg or so).

On the eleventh day, a Persian council of war was held, in which Mardonius and the general Artavazus opposed their arguments. Artavazos proposed the retreat of the Persian army to Thebes, where abundant supplies were gathered and where they could be more easily defended. Prolonging the fight would give the Persians time to succeed in buying off the rulers in some Greek cities.

On the contrary, Mardonius supported the direct attack, because he believed in the great superiority of his army. Finally, Mardonius ignored the advice of Artavazus and the Thebans and ordered them to prepare for battle the next day. In a strong tone, he addressed the commanders of the units, telling them that his own army was incomparably superior to the Hellenic one and that he was the one who made the decision after receiving the command of the army from the king, and not Artavazos. No one objected to Mardonios' decision.

During the night the Macedonian king Alexander I, who was in the camp of Mardonius as an ally of the Persians, crossed the Asopus and presented himself to the Athenian generals (only to Aristides, according to Plutarch), to warn them about the impending enemy attack. The beginning of his words, as handed down by Herodotus, is the following:

"Athenians, I entrust you with these words as a secret, and I forbid you to announce them to anyone except Pausanias, lest you destroy me. Of course you will not I said, if I wasn't very interested in all of Greece. Because I myself am a Greek from an old generation and I would not like to see Greece as a slave and not free".

Alexander then informed them that Mardonius had decided to attack at dawn, despite the unfavorable sacrifices, because he was afraid, in Alexander's own opinion, that the Greeks were gathering larger forces. The king of Macedonia urged them to prepare for battle and advised them, in case Mardonius postponed his attack, to be patient, because the supplies of the enemy army were running out. Finally, he asked to be released after their victory from the Persian yoke in return for this service of his, and revealed his identity:

"I am Alexander of Macedonia," he said, and returned to the Persian camp. This explicit testimony of Herodotus about the Greekness of Alexander and the Macedonians is an important service to history.

After this the Athenian generals went to the right wing and announced to Pausanias the words of Alexander. When Pausanias heard this, out of his fear of the Persians he proposed to the Athenians that they should change sides with the Spartans, so that the Athenians might have the Persians, for the victors of Marathon knew the Persian tactics better than they. The Athenians gladly accepted the proposal: "We would have already proposed it to you, they told the Spartans, if we had not been afraid of offending you."

However, when the Athenians and Spartans began to change positions, the Boeotians realized this and informed Mardonius who immediately ordered a corresponding change in his line-up, to neutralize the movement of the Greeks. As soon as the Athenians found the countermeasure of Mardonius, they reverted to their original arrangement and so did the Persians, so that in the end no change was made.

Mardonius was more impatient than the Greeks for the battle to take place, because he too was pressed by the lack of food and supplies. Another reason, which probably pushed him to battle, was that, while he did not depend on the Persian fleet for his supply, he certainly understood the consequences that a Greek naval victory in Ionia and a revolution of the Asia Minor Greeks would have for his army. So perhaps he was in a hurry to subdue the Greeks, before a victory by the Greek fleet isolated his army in Greece.

Certainly Mardonius waited for twelve days, hoping that Pausanias would make the mistake of attacking the plain north of Asopus, where the Persian cavalry would ensure Persian superiority. It has also been argued that Mardonius postponed the attack because he expected a pro-Persian conspiracy to emerge in the ranks of the Athenian army.

After this Mardonius sent a herald to the Spartans, who, after extolling their bravery, criticized them because the Athenians agreed to face the Persians and not them. He also told them that they did this because they were trembling with fear of the Persians. Finally he suggested that they fight only Spartans and Persians and that Mardonius will accept whoever wins and this victory will be considered the victory of the whole army. None of the Greeks answered the herald and he returned and reported to Mardonius what had happened.

Mardonius considered it a victory that the Spartans did not accept his challenge and full of joy and pride sent his cavalry to attempt a general assault on the Greek lines. As early as the ninth day he was pounding them in various places, but this time the attack was general. The attack ended in success for the Persians.

The Persian horsemen reached the Gargafia fountain, which was on the right wing of the Greeks, near the Spartan positions, and completely destroyed it, covering it with earth. A large part of the Greeks got water from it, because the Persian cavalry prevented the Greeks from taking water from Asopus. With their blockade from Asopos and Gargafia and with the destruction of the supply convoy at the crossing of Dryos Kefali, the Greeks were in danger of running out of food and water.

The Greeks therefore had to either attack immediately on terrain favorable for the Persian cavalry - so Mardonius would have achieved his goal - or retreat to new, more protected positions, near springs, and at the same time attempt to regain control of the passes of Kithairon . A council of war, which met immediately after the loss of Gargaphia, decided to retreat in the direction of the Plataea during the following night, four hours after sunset, if the Persians did not continue the general attack of their cavalry and advance an attack of the infantry until evening.

The place chosen by the Greeks was called Nisos, because it was included between two tributaries of the Oerois river (daughter of Asopus) that flowed into the Corinthian gulf. The island was 15 stadia (2900m) from Asopus and Gargafia. Today, this location has been identified with a very high probability between today's Erythrae and Plataea. Its identification, however, has the disadvantage that it could hardly include the entire Greek army.

It is not excluded that this is again due to an ambiguity by Herodotus and that the plan provided for an extension of the front outside the Island, which, according to what the historian writes, would serve as a starting point for the operation to restore control of the

Kithairon crossings.

THE ALIGNMENT

OF THE GREEKS

After this first success, Pausanias decided to advance and bring his army's array closer to Plataea. The reasons that dictated this decision to him are certainly not known. He was certainly encouraged by the first success and faced with greater confidence in the possibility of fighting on flat terrain. At the same time, he hoped that he would more easily lure the Persians into a confrontation, now that he was in less mountainous terrain.

Finally, perhaps the lack of water forced him to change his position. Herodotus says that the Greek army marched westward along the foothills of Kythairon, past the Hysias, to the territory of the Plataea, and encamped by nations near the fountain Gargaphia (its location is not known today) and the sanctuary of the hero of Plataion Androkratis, which is six stadia (about 1200 m.) from Plataia, on uneven ground with low hills.

While the Greeks were preparing to line up in the new position, an argument broke out between the Athenians and Tegeans about who should be on the left wing. The Tegeans were said to be the most worthy allies of the Spartans and deserved that position. The Athenians replied that "the purpose of the campaign is to fight the barbarians and not to argue. But since you have raised this issue we answer you that since we always do the right thing, it is our paternal tradition to have the primaries". The final solution to the argument was given by the entire Lacedaemonian camp, which shouted that the Athenians were superior to the Arcadians and that the left wing belonged to them.

After that the Greek army lined up as follows:

- -On the right wing the 10,000 Lacedaemonians together with the 35,000 small Helots. On their left, the 1500 Tegeans lined up in honor.

- -On the left wing the 8,000 Athenians and the 700 Plataeans.

- - In the center are all the other Greeks.

THE MOVE TO THE 2ND PLACE

Pausanias might have been looking to provoke an attack by the strong Persian center at that point, so that the two ends (Lacedaemonians and Athenians) could attempt a circular movement, as in Marathon. The fact that Pausanias was later forced to change his position again proves the impossibility of this movement.

Persians

After the end of mourning in the camp of the barbarians, Mardonius, seeing the Greeks that they had descended lower, rejoiced. The tactic of waiting that he had implemented with the volleys of his cavalry, bore fruit as the opponent had moved to the exact point he wanted so that to be able to deploy the cavalry. So he lost no time and moved his troops westward along the north face of the Asopus River and arrayed them as follows:

- -On the left wing and opposite the Lacedaemonians, Mardonius arrayed the Persians who, as they were more numerous, their array had a great length and depth and covered the front of the Tegeates as well.

- -On the right wing and opposite the Athenians, the Plataeans and the Megareans, he lined up the Greeks (about 50,000) who were in the service of the Persian army.

- -In the center and opposite the rest of the Greeks, he lined up the Medes, the Bactrians, the Indians, the Sakas and the rest of the tribes.

WAITING BEFORE THE GREAT BATTLE

Both Mardonius and Pausanias each had their own reasons for not wanting to attack first. Although the Greeks had lined up in a vulnerable position, Mardonius did not seem eager to attack first, preferring instead to wait. the first move by the Greeks that would offer him a comparative advantage. He was smart enough not to underestimate the opponent and considered it too risky to attack him.

THE FIELD OF BATTLE TODAY

The unfortunate outcome of the attacks he had launched with his cavalry and the tragic end of Masistios had convinced him that great caution was required against the Greek phalangites. He had to face not only the best warriors, but also a considerable army, since the ratio of 1:3 (Greeks to Persians) left all possibilities open for the outcome of the battle. So Mardonius was determined to order an attack only when he was quite sure.

But Pausanias also decided that the Persians' defensive position was the most secure and advantageous, rather than crossing the Asopus, exposing the Greek infantry to the advances of the Persian cavalry.

Thus the two armies remained idle in their new positions for eight days, for the oracles, Tisamenus of the Greeks and Hegisstratus the Helios who was in the camp of the Persians, declared to both camps that the omens were good for defense, but not to attack after crossing the river.

On the ninth day, because new fighters were coming to the camp of the Greeks from everywhere, Mardonius, at the instigation of the Theban Timagenis, sent during the night some divisions of cavalry to the passes of Kithairon with a view to placing under his control the strait of the Dryos Kefalon (note Kaza), from where the supply convoys that supplied the Greek army passed. The Persian horsemen managed to block the passage and even capture a supply convoy with 500 ships carrying food from the Peloponnese, mercilessly slaughtering people and animals.

After the loss of the passage, Pausanias began to be pressed for time since he would soon have a problem of feeding his soldiers, but also of general supplies. The Greeks believed that the Persian attack was only a matter of time. But the wily Mardonius had an exasperating patience, and apart from the occasional skirmishes and harassing advances of the Persian cavalry, he did not seem inclined to attack first.

During the next two days neither opponent decided to attack. Mardonius

PERSIAN HORSEMAN

continued to engage in harassing actions. The Persian cavalry constantly provoked the Greeks, prevented them from obtaining water from Asopus, and caused them losses, for the gnawing Thebans, excited for this war, led the horsemen to the point of engagement and then withdrew them, thus making a display of their prowess and their combat capabilities (classic tactical psychological operation).With these actions, on the one hand, they wanted to lure the Greeks into an attack north of Asopus, and on the other hand, with the suspicion of a Persian attack, they constantly kept the heavily armed Greeks in battle tension, causing irritation and fatigue. The strain of the Greek soldiers from the many days of waiting was certainly very great, if we take into account both the weather conditions (August with an average temperature of 32-34 °C) and the weight of their weapons (31 kg or so).

On the eleventh day, a Persian council of war was held, in which Mardonius and the general Artavazus opposed their arguments. Artavazos proposed the retreat of the Persian army to Thebes, where abundant supplies were gathered and where they could be more easily defended. Prolonging the fight would give the Persians time to succeed in buying off the rulers in some Greek cities.

On the contrary, Mardonius supported the direct attack, because he believed in the great superiority of his army. Finally, Mardonius ignored the advice of Artavazus and the Thebans and ordered them to prepare for battle the next day. In a strong tone, he addressed the commanders of the units, telling them that his own army was incomparably superior to the Hellenic one and that he was the one who made the decision after receiving the command of the army from the king, and not Artavazos. No one objected to Mardonios' decision.

During the night the Macedonian king Alexander I, who was in the camp of Mardonius as an ally of the Persians, crossed the Asopus and presented himself to the Athenian generals (only to Aristides, according to Plutarch), to warn them about the impending enemy attack. The beginning of his words, as handed down by Herodotus, is the following:

"Athenians, I entrust you with these words as a secret, and I forbid you to announce them to anyone except Pausanias, lest you destroy me. Of course you will not I said, if I wasn't very interested in all of Greece. Because I myself am a Greek from an old generation and I would not like to see Greece as a slave and not free".

Alexander then informed them that Mardonius had decided to attack at dawn, despite the unfavorable sacrifices, because he was afraid, in Alexander's own opinion, that the Greeks were gathering larger forces. The king of Macedonia urged them to prepare for battle and advised them, in case Mardonius postponed his attack, to be patient, because the supplies of the enemy army were running out. Finally, he asked to be released after their victory from the Persian yoke in return for this service of his, and revealed his identity:

"I am Alexander of Macedonia," he said, and returned to the Persian camp. This explicit testimony of Herodotus about the Greekness of Alexander and the Macedonians is an important service to history.

After this the Athenian generals went to the right wing and announced to Pausanias the words of Alexander. When Pausanias heard this, out of his fear of the Persians he proposed to the Athenians that they should change sides with the Spartans, so that the Athenians might have the Persians, for the victors of Marathon knew the Persian tactics better than they. The Athenians gladly accepted the proposal: "We would have already proposed it to you, they told the Spartans, if we had not been afraid of offending you."

However, when the Athenians and Spartans began to change positions, the Boeotians realized this and informed Mardonius who immediately ordered a corresponding change in his line-up, to neutralize the movement of the Greeks. As soon as the Athenians found the countermeasure of Mardonius, they reverted to their original arrangement and so did the Persians, so that in the end no change was made.

Mardonius was more impatient than the Greeks for the battle to take place, because he too was pressed by the lack of food and supplies. Another reason, which probably pushed him to battle, was that, while he did not depend on the Persian fleet for his supply, he certainly understood the consequences that a Greek naval victory in Ionia and a revolution of the Asia Minor Greeks would have for his army. So perhaps he was in a hurry to subdue the Greeks, before a victory by the Greek fleet isolated his army in Greece.

Certainly Mardonius waited for twelve days, hoping that Pausanias would make the mistake of attacking the plain north of Asopus, where the Persian cavalry would ensure Persian superiority. It has also been argued that Mardonius postponed the attack because he expected a pro-Persian conspiracy to emerge in the ranks of the Athenian army.

After this Mardonius sent a herald to the Spartans, who, after extolling their bravery, criticized them because the Athenians agreed to face the Persians and not them. He also told them that they did this because they were trembling with fear of the Persians. Finally he suggested that they fight only Spartans and Persians and that Mardonius will accept whoever wins and this victory will be considered the victory of the whole army. None of the Greeks answered the herald and he returned and reported to Mardonius what had happened.

Mardonius considered it a victory that the Spartans did not accept his challenge and full of joy and pride sent his cavalry to attempt a general assault on the Greek lines. As early as the ninth day he was pounding them in various places, but this time the attack was general. The attack ended in success for the Persians.

PERSIAN HORSEMEN

The Greeks therefore had to either attack immediately on terrain favorable for the Persian cavalry - so Mardonius would have achieved his goal - or retreat to new, more protected positions, near springs, and at the same time attempt to regain control of the passes of Kithairon . A council of war, which met immediately after the loss of Gargaphia, decided to retreat in the direction of the Plataea during the following night, four hours after sunset, if the Persians did not continue the general attack of their cavalry and advance an attack of the infantry until evening.

The place chosen by the Greeks was called Nisos, because it was included between two tributaries of the Oerois river (daughter of Asopus) that flowed into the Corinthian gulf. The island was 15 stadia (2900m) from Asopus and Gargafia. Today, this location has been identified with a very high probability between today's Erythrae and Plataea. Its identification, however, has the disadvantage that it could hardly include the entire Greek army.

It is not excluded that this is again due to an ambiguity by Herodotus and that the plan provided for an extension of the front outside the Island, which, according to what the historian writes, would serve as a starting point for the operation to restore control of the

Kithairon crossings.

After this decision, throughout the day they endured the attacks of the cavalry and suffered many losses. At the end of the day, however, the cavalry attacks were interrupted. Immediately the Greek divisions began to withdraw from their positions, but they initiated the retreat completely autonomously and moved somewhat individually, without faithfully executing the commander-in-chief's instructions.

Amid considerable confusion, each Greek section occupied a new position, which was not the one specified by the commander's order, either because the section wandered in the night, or because it did not faithfully execute the order, or because it did not coordinate with the movements of the flanks departments. Thus the front lost its cohesion.

The troops of the center of the formation (Megareans, Corinthians, Fleiasians, etc.), the most exhausted by the attacks of the Persian cavalry, left their positions at night and wandered to the walls of Plataea, near the temple of Hera, where

they settled. In fact, shortly before dawn Pausanias, not seeing the center divisions lined up at the pre-agreed point, thought that they had deserted and announced to the Athenians that only they and the Lacedaemonians would fight and invited them to come and line up on his left. But this did not happen because at the time of the movement of the Athenians towards the Lacedaemonians, the Persian attack began.

A senior Spartan officer, commander of the Pitanati company (Pitani was one of the municipalities of Sparta), the captain Amompharetos of Poliados, refused to retreat with his division, because he considered it contrary to Spartan honor to retreat in front of the enemy. At that moment, a herald of the Athenians came who were worried about the Spartans' slowness and saw the whole episode.

An argument ensued with Pausanias and Euryanax who failed to persuade him to start. In fact, Amompheratos picked up a stone with both hands and threw it in front of Pausanias' feet, telling him that this is how he votes, that is, not to take a step back and not to retreat in front of the "barbarians" accusing the other Greeks of being cowards. Pausanias after reprimanding him severely, calling him a maniac and

It is said that the Spartans continued to quarrel until the early hours of the morning and finally decided to move on, leaving him behind, in the hope that being left alone he would follow them, which he eventually did. But thus they were delayed many hours.

Most historians consider Amompharetus' disobedience to the orders of his superiors inconceivable. After all, if Amompharetus really believed that Spartan honor forbade retreat, he would not have retreated after all, but would have fought alone like Leonidas. However, it is not excluded that the delay of the Athenians and Spartans was due to another cause. Perhaps, that is, when it was found that parts of the Greek center did not occupy the position provided for in the original plan, a council of Athenian and Spartan leaders was held for new decisions. Perhaps it was even decided that the Athenians would line up on the left of the Spartans, ignoring the center.

THE 3rd PLACE

The retreat of the Spartans was not delayed, but executed slowly, according to plan. This is how it can be explained, why the company of Amompharetus had not completed its collapse in the morning. This delay was therefore aimed at luring the Persians into an attack. And if this was the purpose of Pausanias, then his success was great, because the Persians fell into the trap and began the attack.

Be that as it may, the main Spartan body, after having traveled ten stadia (2 km) stopped at dawn around the river Moloendas (parap. of Asopus) in the foothills of Kithairon near the sanctuary of Demeter (in front of today's Erythres or Kriekouki). , while light divisions

had managed to clear the supply road and thus achieved one of the main objectives of the enterprise.

The Athenians in full order, as Herodotus tells us, followed an opposite route from the Lacedaemonians and moved towards the plain that stretches between the hill of the Tower of Plataea and the Island. The distance they had to travel was long and it seems that in the confusion from the many changes of positions, they were delayed enough, as a result of which they did not have time to approach the Lacedaemonians. These two parts of it

Thus dawn found the Greeks in the formation of an inverted triangle, with the apex behind where were the overworked sections of the small Greek cities as a reserve, while in front at the base of the triangle to the west the Athenians near the Plataea moving eastward to approach the Lacedaemonians and close the void and to the east the Lacedaemonians in front of today's Erythrae. So there was no formation of a nine phalanx, but three separate divisions that stood apart from each other.

THE MAIN BATTLE

The battle of Plataea took place on the 4th of Boidoromion in 479 BC. that is, on August 27 (otherwise known as September 10), 13 days after the Greeks took second place. At sunrise the Persian horsemen, who recrossed the Asopus, to continue the attacks of the previous day, found that the Greeks had abandoned their positions. Only the laggard company of Amompharetos could be seen retreating slowly across the plain towards the slopes of Kithairon.

Mardonius learned from his horsemen of the Greek retreat. As he was already determined to fight the decisive battle, he wanted to take advantage of the opportunity presented to him. Riding on his horse, he gave his staff the last orders that were to be made and the last words of his life, "they must not escape by anything, we must pursue them until we get them in hand, so that they will be punished as they deserve". His decision seems prudent since the Greek faction was divided into three sections.

The Spartans even retreating would certainly have had some difficulty moving from retreat to defense or attack. However, Mardonius did not suspect the possibility of a trap and it certainly seems that he was lured into a position not so suitable for his cavalry.

Terrible war-cries filled the air from one end to the other of the Asiatic army that eagerly awaited the signal to break out like a bloodthirsty beast. The war banners were raised, first of the Persians and then of all the other nations. Therefore, the Persians and the "snarling" Greeks were the first to advance against these three divisions separately, with Mardonius leading them, who thought that he would not even need to fight, but would easily capture the retreating Greeks (Plut. Aristo. 17, 5).

The Persian "Immortals" and the other cuirassed Medes and Sakas quickly passed Asopus and with them the Bactrians and the Indians in the center and with a shout they all began the pursuit of the Greeks, while on the right they were followed, with no less eagerness and speed, by the Greeks "gnawing", eternal shame of Greece!

Three engagements, one quite far from the other, but with some interdependence, made up the Battle of Plataea. In the first, in the battle that the Spartans concluded with the Persians, the fate of the battle, but also of ancient Greece, was decided. Pausanias asked for help from the Athenians. But the Athenians were unable to reinforce him, because, while they were marching towards her

Pausanias set a trap that was masterfully staged and Amompheratos with his Company with "slow pace" moved towards the main body of the Lacedaemonians which was four stadia (800m) away, calmly watching sometimes the enemies who were weighing and sometimes the Lacedaemonians.

Pursued by the Persian horsemen, without having panicked and with high morale, they joined the Spartan phalanx that had turned around and was waiting for them on the banks of the Moleon river, at the location of Argiopio, where the Sanctuary of Demeter was located. Pausanias performed a sacrifice and ordered his soldiers, while he was sacrificing, to place their shields at their feet and wait, without attempting an attack, before his signal (Plut.Arist.17,7).

Amid considerable confusion, each Greek section occupied a new position, which was not the one specified by the commander's order, either because the section wandered in the night, or because it did not faithfully execute the order, or because it did not coordinate with the movements of the flanks departments. Thus the front lost its cohesion.

AG.TRIADA-RUINS N.IRAS

they settled. In fact, shortly before dawn Pausanias, not seeing the center divisions lined up at the pre-agreed point, thought that they had deserted and announced to the Athenians that only they and the Lacedaemonians would fight and invited them to come and line up on his left. But this did not happen because at the time of the movement of the Athenians towards the Lacedaemonians, the Persian attack began.

MOVEMENT OF GREEKS

An argument ensued with Pausanias and Euryanax who failed to persuade him to start. In fact, Amompheratos picked up a stone with both hands and threw it in front of Pausanias' feet, telling him that this is how he votes, that is, not to take a step back and not to retreat in front of the "barbarians" accusing the other Greeks of being cowards. Pausanias after reprimanding him severely, calling him a maniac and

AMOFERATOS

maddened, he told the Athenian herald to inform the Athenians of the state of things, and further requested them to come over to them and act for their departure like the Spartans.It is said that the Spartans continued to quarrel until the early hours of the morning and finally decided to move on, leaving him behind, in the hope that being left alone he would follow them, which he eventually did. But thus they were delayed many hours.

Most historians consider Amompharetus' disobedience to the orders of his superiors inconceivable. After all, if Amompharetus really believed that Spartan honor forbade retreat, he would not have retreated after all, but would have fought alone like Leonidas. However, it is not excluded that the delay of the Athenians and Spartans was due to another cause. Perhaps, that is, when it was found that parts of the Greek center did not occupy the position provided for in the original plan, a council of Athenian and Spartan leaders was held for new decisions. Perhaps it was even decided that the Athenians would line up on the left of the Spartans, ignoring the center.

THE 3rd PLACE

The retreat of the Spartans was not delayed, but executed slowly, according to plan. This is how it can be explained, why the company of Amompharetus had not completed its collapse in the morning. This delay was therefore aimed at luring the Persians into an attack. And if this was the purpose of Pausanias, then his success was great, because the Persians fell into the trap and began the attack.

Be that as it may, the main Spartan body, after having traveled ten stadia (2 km) stopped at dawn around the river Moloendas (parap. of Asopus) in the foothills of Kithairon near the sanctuary of Demeter (in front of today's Erythres or Kriekouki). , while light divisions

had managed to clear the supply road and thus achieved one of the main objectives of the enterprise.

The Athenians in full order, as Herodotus tells us, followed an opposite route from the Lacedaemonians and moved towards the plain that stretches between the hill of the Tower of Plataea and the Island. The distance they had to travel was long and it seems that in the confusion from the many changes of positions, they were delayed enough, as a result of which they did not have time to approach the Lacedaemonians. These two parts of it

THE FINAL LINE-UP

Greek army they will receive immediately in the morning hours and before they unite the fierce attack of the Persians and their Greek allies.Thus dawn found the Greeks in the formation of an inverted triangle, with the apex behind where were the overworked sections of the small Greek cities as a reserve, while in front at the base of the triangle to the west the Athenians near the Plataea moving eastward to approach the Lacedaemonians and close the void and to the east the Lacedaemonians in front of today's Erythrae. So there was no formation of a nine phalanx, but three separate divisions that stood apart from each other.

The battle of Plataea took place on the 4th of Boidoromion in 479 BC. that is, on August 27 (otherwise known as September 10), 13 days after the Greeks took second place. At sunrise the Persian horsemen, who recrossed the Asopus, to continue the attacks of the previous day, found that the Greeks had abandoned their positions. Only the laggard company of Amompharetos could be seen retreating slowly across the plain towards the slopes of Kithairon.

Mardonius learned from his horsemen of the Greek retreat. As he was already determined to fight the decisive battle, he wanted to take advantage of the opportunity presented to him. Riding on his horse, he gave his staff the last orders that were to be made and the last words of his life, "they must not escape by anything, we must pursue them until we get them in hand, so that they will be punished as they deserve". His decision seems prudent since the Greek faction was divided into three sections.

The Spartans even retreating would certainly have had some difficulty moving from retreat to defense or attack. However, Mardonius did not suspect the possibility of a trap and it certainly seems that he was lured into a position not so suitable for his cavalry.

Terrible war-cries filled the air from one end to the other of the Asiatic army that eagerly awaited the signal to break out like a bloodthirsty beast. The war banners were raised, first of the Persians and then of all the other nations. Therefore, the Persians and the "snarling" Greeks were the first to advance against these three divisions separately, with Mardonius leading them, who thought that he would not even need to fight, but would easily capture the retreating Greeks (Plut. Aristo. 17, 5).

The Persian "Immortals" and the other cuirassed Medes and Sakas quickly passed Asopus and with them the Bactrians and the Indians in the center and with a shout they all began the pursuit of the Greeks, while on the right they were followed, with no less eagerness and speed, by the Greeks "gnawing", eternal shame of Greece!

Three engagements, one quite far from the other, but with some interdependence, made up the Battle of Plataea. In the first, in the battle that the Spartans concluded with the Persians, the fate of the battle, but also of ancient Greece, was decided. Pausanias asked for help from the Athenians. But the Athenians were unable to reinforce him, because, while they were marching towards her

SAKAS ARCHER