THE NORMANDY LANDING (6 IOYNIOY 1944) OPERATION OVERLORD

In mid-1943, the Axis powers still controlled almost all of Europe, and without the immediate intervention of the Western Allies in Europe, Hitler could hope to extend his military dominance over it for years to come. As early as 1942, Soviet leader Stalin was pressing the Allies hard to open a second front in the West. The tested Soviet armies suffered huge losses in the face of the German armored divisions, while in the West the Germans had only second-rate forces to stand guard just in case.

However, Stalin's wish took a long time to come true. The Western Allies were on the one hand reluctant, on the other hand they had practically no possibility for such a large movement so early, despite the apparent willingness of the Americans. The British maintained their reservations about whether a landing in France was feasible before 1944 and finally succeeded in persuading the Americans to agree to a landing in North Africa in 1943.

The landings in Sicily and the Italian mainland that followed delayed preparations for the invasion of France. The invasion of Italy was preceded by plans and thoughts for an invasion of the Balkans, via Greece, in order to open the "Second Front" there. At the Allied conference in Teheran, a definitive date for the opening of the second front was agreed to be May 1944. Stalin, for his part, agreed to launch a simultaneous attack on the Eastern Front and declare war on Japan once Germany was defeated. .

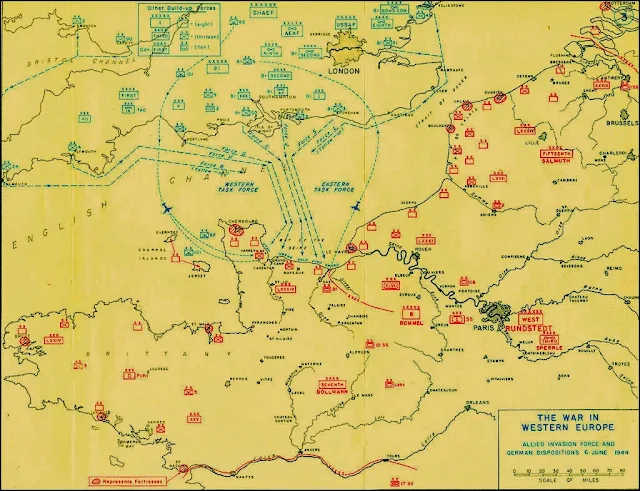

The Normandy Landings, codenamed Operation Overlord, were the Allied landings on the coast of France that took place on June 6, 1944, also known as D-Day. The objective purpose of the landing was to create a bridgehead from Caen to Cherbourg, through which the Allies would pass troops from Great Britain to the Continent

The ensuing Battle of Normandy ended on August 19, 1944, when Allied troops crossed the Seine. The American commander-in-chief Dwight Eisenhower was appointed the head of the whole project. The initial attack was made in two phases: at midnight on the 5th-6th two American airborne divisions and one British fell to the rear, followed at dawn by an amphibious landing of Allied forces beginning at 6:30.

Carrying out the landing required the transport of troops and material from England and Wales by transport planes and ships, as well as fire support from the air and sea. Naval diversion and harassment operations were also carried out to prevent the German Navy from interfering with the landing areas, while the English Channel was cleared of German mines and new ones were laid.

Over three million people took part in the operation, of which 195,700 were the personnel of Allied ships. The landing took place on the Cotantin Peninsula, the east bank of the Orne River and the Seine Bay, on five beaches codenamed Gold Beach, Juno Beach, Omaha Beach, Sword Beach and Utah Beach. It was considered completed on June 30, 1944, when the Allied bridgehead was now established.

By then a total of 850,000 men, 148,000 vehicles and 570,000 tons of supplies had been brought to French shores by 7,000 ships, of which only 59 were sunk. Tuesday, June 6, 1944, shortly after midnight. The BBC interrupts its program and broadcasts the lines from a poem by Verlaine: "The deep sighs of autumn's violins grip my heart with a monotonous melancholy."

At the same time, British and American paratroopers land between the Orne and Dive rivers and on France's Catandin peninsula. RAF planes bomb the artillery batteries located near the coast. A few hours pass and the German soldiers in disbelief face an armada of allied ships emerging through the morning dew. At 6.30 in the morning waves of allied soldiers begin to arrive on the beaches of Normandy. The "greatest day of the war" has begun.

By the time of the Normandy Landings the Allies had already scored several important victories. However, an intervention "in the heart of Germany", according to American President Franklin Roosevelt, was deemed necessary. Thus it was decided to carry out a landing in Western Europe on May 1, 1944, under the code name "Operation Sovereign". The most important concern was the selection of the landing site.

Calais seemed the best target, due to its short distance from the British coast. But the Germans had the same opinion, so the elite troops of the 15th Army guarded the area. Calais was rejected, precisely because it was clearly the best option. Following a suggestion by Lt. Gen. Frederick Morgan, Normandy was chosen as the location of the landing, a choice which was not only "Top Secret", but a higher classification was therefore created, called BIGOT.

In the night before dawn on June 6th, while the paratroopers were fighting in the dark fields of Normandy, the largest fleet, the largest armada that History had ever known, approximately 5,000 ships (4,126 transports escorted by approximately 800 warships, including 2 Greek ones, the corvettes "Tombazis" and "Kriezis") that carried 176,000 troops with their equipment, headed for the five landing beaches, Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juneau, Sword.

The ships supported 7,000 aircraft, while another 2,500 heavy bombers had previously carried out strategic bombing, dropping 10,000 tons of bombs, to paralyze the industrial centers, communication and early warning systems of the Germans, bridges, factories, etc. Beginning at 0630, a few thousand of these fighters came ashore in the first wave of landings.

''Believe me, Lag, the first twenty-four hours of the invasion will be decisive... Germany's fate depends on the outcome.... for the Allies, as well as for Germany, it will be the Greatest Day'' wrote Field Marshal Erwin Rommel to his aide on April 22, 1944.

He commanded nearly 3,500,000 Allied troops, of which close to 1,500,000 were Americans, soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines. The British and Canadians reached almost 1,750,000. Besides them there were French, Polish, Czech, Belgian, Norwegian and Dutch fighters. So many people with their material, 20 million tons, weighed down the English soil so much that it was said mockingly: "If England does not sink it is due to the thousands of balloons and anti-aircraft barriers that keep her afloat."

Never before had an American commanded so many men from so many countries and shouldered such an awesome burden of responsibility. The Supreme Leader, a determined man, ready with a contagious smile, avoided demonstrations and fanfare. He had nothing eccentric or flashy about him, unlike many other famous commanders, except for his four stars of rank, a unique insignia band and the flaming sword, insignia of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force.

The enormous responsibility of leading so many human souls into battle weighed heavy on his shoulders. His stay in a caravan at Southwick House in southern England was simple, as befits a campaign. He usually held meetings with his staff in the tent next to the caravan. The task undertaken by the Joint Chiefs of Staff was summed up in one paragraph:

"You will enter the continent of Europe and, together with the other United Nations, you will undertake operations which will have as their objective the center of Germany and the destruction of the Armed of the Forces....”

THE HOURS OF WAITING

As of May 17, he had decided that D-Day should be one of June 5, 6, or 7 that had two of the key conditions for a landing: an advanced moonrise and a shortly after dawn low tide. . Finally, the landing was chosen to take place on June 5. At 9.30pm on Sunday 4 June, Eisenhower's Senior Commanders and their chiefs of staff met in the library of Southwick House to make the final decision on the landing.

The previous day, weather conditions and forecasts forced Eisenhower to decide on a 24-hour postponement, despite Montgomery's contrary opinion. The RAF's chief meteorologist, Ensign Stang, began the briefing. There was absolute silence and everyone's eyes were fixed on him: "Gentlemen... There have been some sudden and unexpected developments in the situation,” he began. A new weather front had been spotted moving in from the Azores which would gradually bring clear weather to the attack areas over the next few hours.

This improvement would last throughout the next day and into the morning of June 6. Then the weather would start to deteriorate again. As soon as Stang finished the briefing questions for sure prediction came raining down. He, however, refused to promise more: "If I answered your questions I would not be a meteorologist. I would be God." Science has come this far. The decision to land was now a matter for the generals.

Eisenhower after hearing the opinion of his commanders felt his shoulders even heavier. By his decision millions of people would be led to glory or ruin. With folded arms, looking down at the table, he looked eerie and lonely. Minutes passed in complete silence. Turning to his commanders, he says, “I give the order to land half-heartedly. But you have to …." The cube is cast! Eisenhower and his commanders hurried out of the library.

They had to give the orders for the greatest landing in history, which would put an end to Hitler's insanity to dominate the world. On the other hand the fifty-one-year-old Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, known as the "Desert Fox", now in command of Army Group B, the most powerful German force in the West, whose headquarters were in the tower of La Roche-Guillon, had the enormous responsibility of repelling the Allied offensive in Europe when it was about to begin.

From the first day he arrived in Paris in November 1943, the problems of where and how to meet the Allied attack had imposed an almost insurmountable burden on him. The much-vaunted impenetrable "Atlantic Wall" was not as German propaganda made it out to be. He made enormous efforts to improve and organize the fortifications on the potential landing beaches. He was in constant overdrive. He was preparing to fight the most desperate battle of his life.

He had under his command more than half a million men manning the defensive line along the coast, 1280 km. His main force, the 15th Army was concentrated at the narrowest point of the English Channel, between France and England. On May 19, he wrote to his wife Lucia-Maria, who trusted her with everything. “Hopefully I'll be able to move on with my plans faster than before...I wonder if I'll be able to spare a few days in June to be away from here. Right now there is no chance."

Rommel's assessment that he sent to his superior, Field Marshal von Runstedt, at his headquarters, the well-known OB West (Oberbefehlshaber West), who was responsible for the defense of all of Western Europe, wrote that the Allies had reached a "high degree of readiness". but that "according to existing experience this does not indicate that the descent was immediate . . . ."

This time Rommel's assessment proved wrong. At 7 o'clock on the morning of Sunday, June 4, Rommel set off in his car from La Roche-Guillon for Germany. He was accompanied by Lag's aide-de-camp and Colonel von Tempelholf. A special and very human reason made him be close to his wife on Tuesday, June 6. She was celebrating her birthday.

On that stormy Sunday night of June 4th the landing forces were still waiting all over England for the order to embark. The men loaded onto the ships waited in loneliness, worry, fear. Eighteen hours had passed since the order to wait had been given. They were thinking of their families, their wives, their children, their loved ones. And everyone was talking about the battles that awaited them. No one could imagine what D-Day would look like. Everyone was preparing to face it in their own way.

But those who suffered the most were the soldiers of the convoys who, after suffering all day with the storm of the English Channel, turned back, soaked and emaciated, because of the postponement. At 11 pm all the ships had sailed again. At midnight the coast guard boats and destroyers began to assemble the convoys again, a huge chore. This time there would be no reprieve.

Monday, June 4, dawned. Fog, like a shroud, covered the shores of Normandy, that morning. The rain kept falling. Beyond the shores lay irregular fields, full of hedgerows. Countless battles had been fought over them and there would be even more. Since Roman times they had known many invaders. The fields enclosed by high embankments had bushes and trees on them that had been used as natural fortifications. The inhabitants of the small villages, unknown to most of the world, lived for four years under the occupation of the Germans.

At Vierville, one of these villages, the German gunners in their gunnery and camouflaged forts on the edge of the coast, had begun their daily work. It was the shore that would soon become known as Omaha Beach. The great army, men and women, of the resistance, for four years now, has been waging a silent war that often may not have been spectacular, but it was always dangerous. Thousands had been executed and even more were in concentration camps. In the previous days they had received several coded messages from the BBC warning that the invasion was imminent.

One of them was the first verse from Verlaine's poem "Chansons d'Automne" broadcast on June 1st. They eagerly awaited the second verse, as well as other messages that would give orders for the pre-agreed sabotages. "It's hot in Suez" for sabotaging the railway network and hardware and the other "The dice are on the table" for cutting telephone and telegraph cables. Even then the resistance leaders would not know the exact area of the invasion.

Guillaume Mercande, leader of the sector that included the Omaha Coast area on the evening of Monday, June 5, was in the basement of his bike shop in Bayeux when he heard "It's hot in Suez." He was out of breath. After a short pause the announcer said "The dice are on the table". It was a moment he would never forget, as he later said. Other messages followed, involving other resistance groups, each of whom knew what to do. He turned off the radio and left, immediately, to carry out the sabotage with his team.

Monday, June 5, was a quiet day for the Germans, without any surprises. The weather was bad with constant rain. In Paris, at Luftwaffe Headquarters, the head of the meteorological service, Colonel Walter Staibe, told them that the day was favorable for rest. It was doubtful whether the Allied air force could, on that day, carry out its usual operations.

He relayed the same prediction to OB West, the headquarters of Marshal von Rudstedt, who planned to inspect the next day, with his son, a young lieutenant, the defensive works on the coast of Normandy. The marshal attached great importance to weather reports. By the last report he could see that bad weather was helping him miss his headquarters.

Later that day, shortly after 13:00 noon, less than 12 hours until D-Day, the report "Assessment of Enemy Intentions" was transmitted from OB West to Hitler's Headquarters, OKW (OberKommando der Wehrmacht). , which said: "The systematic and sharp increase in airstrikes indicates that the enemy has achieved a high degree of readiness." He then estimates the potential invasion front to be somewhere in the region of a total of 1,280 km, and continues: "There is no possibility of an imminent invasion...."

The assessment turned out to be completely wrong. At all levels of the German administration the bad weather had worked like a hypnotic. All had based their estimates on previous experience of Allied landings in North Africa, Sicily, Italy, where the Allies had not attempted a landing unless the chances of favorable weather conditions were almost absolute.

At Rommel's Headquarters in La Roche-Guillon, work continued as if the field marshal were present. His chief of staff Major General Speidel found an opportunity, helped by the weather, on the evening of Monday 5 June to organize a dinner with several guests. In Saint-Lo, at the Headquarters of the 84th Regiment, Major Friedrich Hein, an intelligence officer, early that evening, planned a small gathering, because their commander, General Erich Marx, had his birthday the next day.

Early in the morning on Tuesday 6th June, all Senior Commanders in the Normandy region would take part in a major anti-landing exercise on paper in Rennes. So almost all the top officers, from Rommel down, had left the front right on the eve of the landing. They all had a reason. As if some strange fate had seen to it that they were absent from their posts at the critical hour.

The damage was compounded when the German High Command decided to move the last Luftwaffe fighter squadrons in France even deeper into the interior, so that they could not reach Normandy. The reason was that they needed them for the defense of the Reich.

THE PREPARATIONS FOR THE DEPARTURE

In early 1944 the south coast of Britain was literally one giant camp, with 3.5 million troops preparing for the largest amphibious operation in history. Bombers and the French Resistance were destroying German radars so that they could not record the movements of ships and planes in the English Channel, as well as road junctions, to prevent the transport of reinforcements to the fronts. These attacks were developed along the entire length of the French coast, so as not to betray the exact point of the Landing.

The determination of the specific day of attack was made taking into account weather factors. The paratrooper operation could only be done when the moon was full. Also the attack would have to take place when the tide was at mid tide because of the traps the Germans had set. This combination of weather conditions coincided with June 5, which was designated as "D-Day", the day operations began.

On 1 June the BBC broadcast the first half of Verlaine's verse, as a message to the French Resistance that the D-Day would begin in a few days. But the Germans had also been informed of this. And while the half-verse was repeated every day, the weather grew worse and worse. On the 5th of June the sea was raging, so that any idea of a landing seemed unrealistic. Indeed, the landing was postponed until the following day.

But the weather improved little and the German officers became complacent; it was not possible to make a landing in bad weather. Several left for Brittany, where it was unfolding - what irony! - simulated Allied landing exercise while Rommel was in Germany celebrating his wife's birthday. Adolf Hitler was sleeping in his headquarters in Berchtesgaden. At that time of night Eisenhower was hesitantly giving the signal for the D-Days to begin. The BBC broadcast Verlaine's entire verse. From that moment June 6, 1944 would go down in history.

THE POETOIMASIA OF SYMMAX

In January 1944, the Allies appointed Nwight Eisenhower ("Ike") commander of the Supreme Command of the Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), while General Smith was appointed chief of staff of the Supreme Command. British Air Marshal Tinder was named Ike's second-in-command, Montgomery commander of all Allied ground forces to land, Admiral Phamsey commander of the navy, and Air Marshal Lee-Mallory head of the landing air force.

Montgomery's first decision was that five divisions were the minimum necessary for the initial landing, and as the so-called Montgomery Plan was finally formulated, the invasion force did include five infantry divisions, two US, two British and one Canadian, which would land on five coasts with the codes Omaha, Utah, Gold, Juneau and Sword. Two American airborne divisions and one British were to secure the ends of the landing beaches.

The Americans who would land were assigned to the 1st Army, commanded by General Bradley, while the British Canadians were assigned to the 2nd Army, commanded by British General Dempsey. Both armies formed the 21st Army Group commanded by Montgomery. The invasion would be supported by more than 13,000 fighter, bomber and transport planes, against which the Luftwaffe could field no more than 400.

THE GERMAN SIDE

Hitler was aware that the Western Allies would attempt a landing across the Channel, but it was not until November 1943 that he accepted that this threat could no longer be ignored and in his directive number 51, he announced that the defense in France would was getting stronger. At the end of the year he appointed Pommel as inspector of the coastal fortifications, the so-called Atlantic Wall, and then commander of Army Group B', which consisted of Tolmann's 7th Army in Normandy and Brittany and von Salmuth's 15th Army in the area of Pa-Nte-Calais.

The supreme commander of the West was Marshal Poudstedt. Thanks to Pommel's tireless efforts in the early months of 1944, the work of fortifying the Atlantic Wall was greatly accelerated, millions of mines were laid and thousands of traps and obstacles were set on the beaches of the French coast and in the fields inland. His source of disagreement with Pudstedt was the matter of the armored divisions that were stationed in the area and were the spearhead of the Germans.

After his experience in his last battles in Africa, Pommel had concluded that any movements towards the French coast would be impossible due to the dominance of Allied air power and argued that tank forces should be stationed close to the coast to have the ability to intervene in time, before the Allies were able to establish permanent bridgeheads there.

Bridgested believed that overwhelming Allied naval and air firepower would gradually destroy the tanks if they were stationed near the coasts and argued that they should remain concentrated as a reserve in the interior of France and counterattack en masse when the Allies advanced. beyond the coasts, in order to cut them off from them and their supply and throw them into the sea.

Hitler, resolving their difference, made the situation worse by placing three armored divisions under the command of Army Group B', while the other four formed the Panzer Group West, under the command of von Schweppenburg, but which could not be moved without the Hitler's approval.

THE GERMAN EXPEDITION

At the same time, a gigantic effort to misinform the Germans, "Operation Endurance", was launched in order to convince the Germans that the landing would take place in Calais. For this purpose the Allies mobilized all their ingenuity. They built fictitious bases in Kent, England with tanks, vehicles, and artillery batteries made of plywood, tires, and crumpled paper, where there was constant truck traffic (always the same ones coming and going).

German spy planes "unfortunately" managed to avoid anti-aircraft fire and reported the "preparations" they saw, and British counterintelligence eliminated or captured almost all German spies on British soil, who falsely reported that the landings would was held in Calais.

"Operation Endurance" was crowned with absolute success. German Intelligence and all top Nazi officers, with the exception of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, were convinced that the landing would take place at Calais. It is alleged that Adolf Hitler had suspected that the landing would take place near Caen, in Normandy, but he did not pursue this premonition with sufficient vigor. The result was that 19 elite divisions remained at Calais until the end of July, staring out at the empty sea while the outcome of the war was decided in Normandy.

Deceiving the enemy as to the landing area was an important part of careful Allied planning, for if the Germans concentrated their scattered forces on the western front at one point, they would be able to repel the invasion. Aich's staff, in order to mislead the Germans into believing that Calais, rather than Normandy, would be the landing area, created a fictitious 1st Army Group, with a battle formation larger than that of the 21st Army Group of Montgomery.

This fictitious force was based in the Hanover area, directly across from the supposed objective of the Calais, and those responsible for the deception operation began constructing plywood and tarpaulin camps, which were filled with plastic models of tanks and vehicles. . A vast armada of plastic models of divers anchored in the Thames estuary. Ike appointed Patton, the general the Germans valued more than any of his American counterparts, as its commander.

He made sure that British newspapers regularly ran pictures of him at public gatherings where he was the official speaker. Naval units conducted exercises near the location of this "shadow army", while a network of wireless stations was set up that broadcast imaginary orders to the imaginary units, which succeeded in convincing German analysts of these broadcasts that there was a significant military concentration in area.

A careful bombing plan completed the trick. During the weeks leading up to the landings, the aviators dropped more bombs on the area of Pais-de-Calais than anywhere else in France. The deception operation with Patton's non-existent 1st Army Group was not the only reason German commanders failed to deduce the correct location of the landing area.

The British Royal Navy had made German naval patrols in the English Channel impossible, and Allied bombers had destroyed most of the German radar units controlling the air and sea near the landing shores. The Luftwaffe could have pointed to the frantic gathering of troops and supplies in the South, directly across from Normandy.

But Allied air supremacy and constant air raids on Germany had left her no room for serious reconnaissance action over the Channel. Finally, the Allies, with the interception of Ultra system messages, were able throughout the preparations for the landing to check whether the German deception plan was working, since the decoding of the encrypted signals gave them a clear picture of where German forces had been deployed.

Although American commanders doubted that the deception operation would be a complete success, it exceeded all expectations. The Germans believed that Pat-Nte-Calais was the actual landing area, even after June 6th. Nineteen strong enemy divisions, including four armored ones, were waiting to land in this area, when their presence in Normandy could play a decisive role in the outcome of the titanic battle for control of the coast.

THE LANDING DATE

On May 8, 1944, General Eisenhower set the landing date as June 4th or 5th. The troops were informed of this in the last week of May, and by June 3rd they had embarked on landing craft in English ports. On May 29, the chief meteorologist of the Supreme Command of the Allied Expeditionary Force had given an optimistic forecast for the weather conditions of the first week of June, and based on this all preparations had been made for the landing on June 5.

However, on the evening of Saturday June 3rd, when he informed the supreme commander that on June 5th there would be low clouds, rain and gale force winds and any forecast beyond 24 hours was impossible in advance, it was decided to postpone the final decision on the landing for seven hours. At 04:30 on the morning of Sunday 4th June, a second meeting of the Allied leaders was held, in which they were informed that the sea state would be better, but the low cloud cover would not allow the use of aviation.

Although General Montgomery expressed his willingness to proceed with the landing on June 5th, General Eisenhower decided to postpone it for 24 hours. Thus the ships which had already embarked with the troops, returned to their ports. On Sunday night, the same meteorologist informed Eisenhower that the rain that was still falling would stop, the weather would improve, but the air and sea conditions on June 6 would not be ideal for a landing.

Eisenhower and his staff realized that if the landings did not take place on June 6th, then they would have to wait for the right tidal conditions on June 19th. The troops would have to be disembarked from the ships and the danger to their safety as well as their morale would be great. At 21:45 Eisenhower announced his decision. "I'm sure I have to give the order... I don't like it, but that's it... I don't see how we can do anything else."

The order was issued and on the evening of June 5th the planes carrying the paratroopers began to take off from the airfields and the 5,000 ships of the largest fleet ever assembled in history began to cross the waters of the English Channel, heading for the shores of Normandy. Operation Overlord had begun.

ORGANIZATION OF THE OPERATION

EARLY

The British had been pressing early on for an Allied landing on European soil. They also had as an unexpected ally Stalin, who was pushing for the creation of a second front to relieve Russian pressure from Germany. The Americans, however, were much more cautious: They knew that an operation of this magnitude needed very careful preparation, in order not to end in a tragic failure (as had happened in Dieppe with the Canadians in 1942). It was decided that the whole of North Africa should be occupied before a landing anywhere in Europe was possible.

At the Casablanca Conference in January 1943 it was found that the climate had now developed to permit the planning of a major amphibious operation in Europe. It was initially proposed that in August 1943 it would be possible to create a "bridge" between Britain and the Cotentin Peninsula in Normandy, from where a large-scale operation could be launched. However, after more mature thoughts, this plan was deemed excessive and was abandoned.

THE CASABLANCA CONFERENCE

The Casablanca Conference was a meeting of Allied leaders held in Casablanca, a city in (then) French Morocco from January 14 to 24, 1943 under the code name "SYMBOL". It was described as the most controversial conference of the War. The conference, at the level of leaders, was attended by American President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Absent was Joseph Stalin, who, although invited, refused to attend, citing the imminent Battle of Stalingrad.

The two leaders had with them all their chiefs of staff and important military figures. French rival generals Charles de Gaulle and Henri Giroud were also present.

Before the Conference

On November 8, 1942, the Allies landed on the shores of (then) French North Africa, carrying out an operation nicknamed "Operation Torch". The operation had been decided despite initial American mistrust and under pressure from Stalin, who demanded that the Anglo-Americans open a front in Western Europe as quickly as possible to relieve the Red Army on the Eastern Front. Indeed, "Operation Sledgehammer" was planned with the aim of the ports of Brest and Cherbourg thus obtaining a small bridgehead on European soil.

The Americans initially favored the plan, but the British strongly opposed it, arguing (correctly) that neither many landing craft were available nor capable of air and sea support for such an undertaking. This is how the implementation of the "Torch" began, with a strong reluctance of the Americans, who did not consider that "the road to Berlin passes through North Africa". At the beginning of 1943 it was already apparent that the outcome of the operation was what was expected.

German and Italian forces would be permanently expelled from North Africa. A number of issues remained to be clarified, such as the handling of the problem created by Admiral Karl Deinitz's submarines in the Atlantic (Battle of the Atlantic), how forces would be distributed on the various war fronts, what the Allies' next step should be, and, finally, from Churchill's point of view, there was the question of how the warring French generals would reconcile.

The British wanted continuity of operations from the Mediterranean side. Churchill even described Italy as "the soft underbelly of Europe". The Americans instead wanted a cross-Channel invasion, knowing that in such a case the British would bear the brunt, which would allow them to save resources for the massive Pacific effort against Japan.

The Preparation

The conference took place in the Anfa district of Casablanca and the discussions were to take place in the hotel of the same name (Anfa Hotel). Two mansions were allocated for the residence of the leaders, two more were allocated for the accommodation of the chiefs of staff, while the entire district was fenced off and armed guards were densely lined up behind the wire fence. Essentially, the conference had no serious objective. Indeed, without the presence of Stalin, it lost a large part of its importance.

All her issues could be resolved without her. However, President Roosevelt "wanted to take a trip," as presidential adviser Harry Hopkins recounts. Because he did not want too many formalities, he begged Churchill "not to burden his foreign minister", as he would have done the same. In fact Roosevelt circled halfway around the world before ending up in Casablanca, passing through Trinidad as well.

This unnecessary move almost cost the Allied leadership dearly: the plane carrying Churchill caught fire, while the one carrying Eisenhower lost two engines in flight, landing the commander-in-chief with a parachute on his back and a bruised knee from vibrations.

Churchill, on the other hand, had pre-planned what he would ask of the American, which was none other than the extension of hostilities in the Mediterranean. He loaded a ship with documents (Cartier calls it a "floating staff") and took with him (like Roosevelt) all his chiefs of staff. He also asked de Gaulle to accompany him, without informing him beforehand. He justified the lack of information by arguing that if the conference had been announced, multiple security measures would have been needed.

The obstinate Frenchman, knowing that this was exactly where his rival's headquarters were, initially offered an emphatic "no" and Churchill departed alone. He re-invited both Giroud and de Gaulle "on behalf of the American president and the British prime minister". Giroud arrived immediately, de Gaulle continued to refuse, arguing that this was a purely French matter and did not need foreign intervention.

The irritable Churchill became so irritated that he threatened de Gaulle, sending him a stern telegram, that he would withdraw his support and cast him aside. Under this suffocating pressure De Gaulle caved in, although he only came to the conference on the ninth day.

The Conference

Present at the conference were:

British Side

Winston Churchill, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

Admiral Sir Alfred Dudley Pickman Rogers Pound

Air Marshal Charles Frederick Algernon Portal

Air Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder

General Sir Alan Francis Brooke

Marshal Sir John Greer Dill

Marshal Sir Harold Alexander, head of British forces in the Middle East

Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten (Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas George Mountbatten)

General Sir Hastings Ismay L. Ismay)

American Side

Franklin Roosevelt, president of the USA

General of the Army and Air Force Henry Arnold (Henry Harley "Hap" Arnold)

Admiral Ernest King (Head of the American fleet)

General George Marshall (George Catlett Marshall), chief of the US

Chief of Staff Dwight Eisenhower, head of Operation Torch

Averel Harriman, presidential adviser

Harry Hopkins, presidential adviser

Robert D. Murphy, special representative of the president on staff of Eisenhower

Lt. Col. Eliot Roosevelt, son of the president

French Side

General Charles de Gaulle, head of the "Free French"

General Henri Onoré Giraud, military commander of French North Africa

Several senior officers and three weapons. A major absentee from the conference, Stalin. The holding of the conference in his absence reinforced in the mind of the Soviet leader the impression that plans were being drawn up without his participation and behind his back, without him being fully informed.

Stalin's suspicion was further strengthened after the decisions of the conference and continued to increase throughout the course of the war, to end, after its end, in the beginning of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. According to the New York Times reports, both Stalin and Chiang Kai-shek were kept informed of the conference's decisions. On the same sheet the response states that both leaders were ultimately satisfied with the decisions of the conference.

Decisions

The basic decision of the conference was that the Allies' struggle should continue until the point called the "bitter end", that is, until Nazi Germany was led to unconditional surrender. The same would apply to both Italy and Japan. It was also agreed that none of the Allies would accept a separate surrender of any of the Axis powers (eg Italy was to surrender to the Allies and not to Britain or the United States).

The truth is that Churchill opposed the Unconditional surrender proposal. He did not think that the fury of Allied revenge should fall upon Germany. That is why he later clarified that "unconditional capitulation does not mean a willingness to take revenge against the German people". Churchill feared, and as it turned out quite rightly, that these two words destroyed whatever opposition existed inside Germany:

It gave the Nazis the springboard they were looking for to support their decision to fight to the death. These two little words were excellently exploited by Joseph Goebbels in his propaganda. Understandably, the opponents of the Hitler regime had no choice but to stop all their actions.

The British argued strongly and Churchill personally countered Marshall's view of a "small" landing on the northern French coast towards the summer of that year. He demonstrated that such an undertaking at this stage of the war would simply result in an easy victory for Hitler, given the air superiority of the Luftwaffe in that area. In addition, the available landing craft were at that time numerically too few to transport the required troops, while the presence of German submarines was particularly worrisome.

Instead, Churchill gave his approval to the provision of strong support to the Americans from Australia and New Zealand, Commonwealth member countries, in the Pacific theater of operations. Churchill also assured that British operations in Burma would be expanded with the aim of strengthening Chiang Kai-shek in China. In return for this gesture, Roosevelt agreed to the Allied Invasion of Sicily.

It was also agreed to begin and intensify air raids against German soil from British airfields with the participation of both air forces (RAF and USAF). This conference was the last in which Churchill could dictate the goals of the allied effort. After this conference the Americans realized that because of their power they were the main factor in the Alliance and they would start to act accordingly.

Initially the two French leaders, although strongly opposed to the Vichy Government, had developed a climate of intense coldness, if not antipathy, in their relations. These "obstinacy" had tired both Churchill and Roosevelt. The American president, on the other hand, considered de Gaulle a representative of "old" France, with colonialist and absolutist tendencies, while at the same time he considered him arrogant.

On the other hand, Giraud believed that De Gaulle had also participated in the murder of Admiral Darlan (in fact, he thought that Darlan's killer had been sent by De Gaulle). On Sunday 24 January, the last day of the conference, Churchill and de Gaulle have another stormy discussion, in which de Gaulle insists on making no commitments. The two men then go to meet Roosevelt, who, after unsuccessful attempts to draw up a joint communiqué, decides to use another method with de Gaulle.

He starts a calm conversation with him, during which he asks if he would agree to shake hands with Jiro. De Gaulle answers "yes". "And you're going to do that in front of the photographers?" "I shall do it for you," replies the Frenchman. Journalists are invited into the room and take a picture of the two men exchanging a handshake, which displays the image of reconciliation. Giroud even agrees to have de Gaulle send him a representative to organize direct contact between French Africa and London (de Gaulle's headquarters).

From this point of view, the conference took on great importance for France. The BBC reported: "The two Frenchmen became the joint chairmen of the French Committee for National Liberation" ("The two Frenchmen became the joint leaders of the French Committee for National Liberation").

CREATION OF COSSAC

Already, since December 1942, a mixed group had been formed, which was initially called "COSSAC" from the initials of the words "Chief of Staff to Supreme Allied Commander". British Major General Frederick E. Morgan was appointed head of this group, who led the following officers, by branch:

Naval Branch: Rear Admiral PL Vian (Br), Captain H. Tz . Wright (HJ Wright) (USA)

Army Branch: General CA West (Br), Colonel J. T. Harris (JT Harris) (USA)

Air Branch: R. Graham (Br) Brigadier General RC Candee (USA)

Command Branch: General N. Brownjohn (Br) ), Colonel FL Rash (USA)

Intelligence Branch: General P.G. PG Whitefoord (Br)

Until he was appointed head of the operation, the status of COSSAC was rather strange, as Morgan and those around him were organizing an operation with many military units, which had not yet been formed, and the landing craft that they intended to use had not been built but not even designed. The method they followed was as follows. The coordinating Committee of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CSS) was based in Washington.

It communicated to COSSAC the problems that needed to be addressed and COSSAC proposed relevant solutions. Correspondence between these bodies is housed in archives, which form "one of the greatest staff memorials ever built". This Staff presented the first result of its work at the Quebec conference in May 1943. The first issue they faced was the determination of the landing site:

Holland was rejected because of the flooding of its coasts, Belgium had suitable coasts but with very strong coastal currents, Brittany presented suitable coastlines, but was relatively remote from England while communications with the rest of France were problematic. Thus, the "lot" fell on Normandy and its two regions, Upper (Haute) and Lower (Basse).

Two COSSAC groups were formed, each advocating for these two areas, arguing for their appropriateness. The group's arguments for Lower Normandy prevailed and so the areas of the Cotantin and Calvados peninsulas were chosen as the most suitable.

CREATION OF SHAEF

Churchill, foreseeing early on that the Americans would demand the leadership of the "Overlord" operation, which he could not refuse them, took the initiative and proposed to Roosevelt, at the Quebec Conference, the appointment of an American head of the business, ignoring the fact that he had already proposed Alan Brooke to lead it. Roosevelt, of course, immediately agreed, and while he initially intended General Marshall to lead, Dwight Eisenhower eventually prevailed.

His official appointment was made in January 1944 and "Ike" settled in London creating the "Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Forces" (Supreme Headquarters of Allied Expeditionary Forces, SHAEF). COSSAC joined SHAEF and Morgan was named "Deputy Chief of Staff".

Morgan's original plan (which he himself had expressed reservations about) did not stand up to criticism. Its first and foremost critic was the British Chief of Army Staff Bernard Montgomery, who intervened so forcefully ("either your plan will change or me") that it was significantly revised. The original three strike divisions became nine and instead of one airborne division three would be used.

The original date of the operation was also revised: Instead of May 1st, it was decided to start on June 1st, to strengthen the forces with the industrial production of another month. Meanwhile the forces that had already begun to gather in Britain were colossal. About 3.5 million men and 20 million tons of material. So they said about Britain. "If the island doesn't sink, it owes it to the anti-aircraft defense balloons that keep it afloat."

The British and Americans, however, managed to solve the enormous problems created by this accumulation. There the term "logistics" (rendered as "Supply Chain Management" in Greek) is introduced for the first time for housing/feeding the men and storing the material.

THE TOPOGRAPHY OF THE

NORMANDY BUSINESS LOCATION

Normandy is a vast region in the north of France. Normandy includes the upper reaches of the Seine River and its estuaries, areas north of Paris and to the west the Cotentin peninsula, where the port of Cherbourg is. It occupies a total area of 29,906 km² and, according to the 1999 census, has 3.2 million inhabitants. Its inhabitants are called Normands. In 1956 French Normandy was divided into two large departments, Haute Normandie and Basse Normandie.

Upper Normandy includes the departments of Seine-Maritime and Eure. It is home to the largest city of Rouen, capital of the department of Saint-Maritime with 385,000 inhabitants. Another important large city is Le Havre, with 247,000 inhabitants. Upper Normandy has a total area of 12,317 Km2, and a population, according to the census (2006), of 1,811,000 inhabitants.

Lower Normandy includes the counties of Calvados, Orne and Manche. Its largest city is Caen, capital of the Calvados prefecture, with 200,000 inhabitants. Lower Normandy has a total area of 17,568 Km2, and a population according to the (2006) census of 1,449,000 inhabitants. The Channel Islands, occupying a total area of 194 Km2, are under the personal rule of the Queen of England who bears the title "Duchess of Normandy".

The area was conquered in the 3rd century BC. by Gauls who came from neighboring Belgium. At the time of the Roman conquest, there were nine different Gallic tribes in the area. The Romans transformed the area with many works. At the beginning of the 4th century AD Christianity entered the region, while it received many cruel attacks by Saxon pirates, which were repelled by the king of France, most notably in (406).

In 885 the Viking warlord Rollon of Normandy (Rollon), in the service of the king of Denmark, invaded France with his homosexuals. The fighting spirit of his army and the looming threat of Rollos' dissolution of the Frankish state forced King Charles III the Simple to capitulate to him (886). He granted him a large share in the borders of his state, on the condition that he protect it from the raids of the remaining Viking warriors. Rouen was designated as the capital of the new duchy.

Rollo named his duchy "Normandy" in memory of his Norwegian ancestry, since Norman was the name of Norway in the language of the Vikings. The first to actually take the title of duke of Normandy was Rollo's grandson, Richard I. Rollo and his descendants ruled Normandy as independent dukes. His direct descendant was William the Conqueror, who completed the conquest of England and, after the Battle of Hastings, was crowned its king (1066) under the name of William I.

Since then, Normandy was in the possession of the English kings, who also bore the title of Duke of Normandy, until 1204, when it was occupied by King Philip II of France. In 1259 the King of England Henry III definitively recognized, with the Treaty of Paris, the French occupation of Normandy, but the English monarchs never gave up their ambitions in Normandy, continuing even formally to have the title of duke.

During the Hundred Years' War, English interest in Normandy was rekindled, as it was one of their main objectives. Eventually, King Henry V of England captured Rouen (1419) with most of the Norman lands. The English kept it in their possession for about a decade, so with the battle of Patay, the reconquest of the French territories with Joan of Lorraine, and the coronation of the King of France, Charles VII (1429), Normandy returned to the French.

The English never stopped claiming their rights in Normandy, which was also seen in 1801 when the King of England, George III, declaring the union of England and Ireland, also laid claim to Normandy. In Normandy was the final battle that decided the end of the Second World War, and the crushing of Hitler's Nazi forces on the Western Front.

The landings took place on five Normandy beaches, codenamed "Utah beach" (USA), Omaha Beach (USA), Gold Beach (Britain), Sword Beach (Britain) and Juno Beach (Canada). By the time the Normandy Landings took place, the Allies had already scored several major victories on the Eastern Front and in Italy. The intervention was deemed necessary according to the opinion of American President Franklin Roosevelt, in order to end the bloody World War II.

Following a proposal by Lt. General Frederick Morgan, Normandy was chosen as the landing site. The Normandy Landings took place on Tuesday, June 6, 1944. The Battle of Normandy, which followed the landings, while expected to last only a few weeks, lasted three months due to the fierce resistance of the Germans, who fought to the death, and had over 400,000 dead and wounded. Allied forces also had 37,000 dead and 100 - 150,000 missing and wounded.

On August 16, 1944, Adolf Hitler ordered a final retreat and the battle ended 4 days later at the Falaise enclave, where 150,000 Axis soldiers were surrounded by Allied troops and 50,000 of them were killed or captured. On August 15, 1944, Allied forces landed in Southern France and, on August 25, French General Charles de Gaulle entered Paris in triumph.

The landing of the Allied forces had a significant cost to the inhabitants of Normandy: 20,000 inhabitants were tragically killed by Allied bombing, while entire towns and villages were partially or completely destroyed by bombing and fighting.

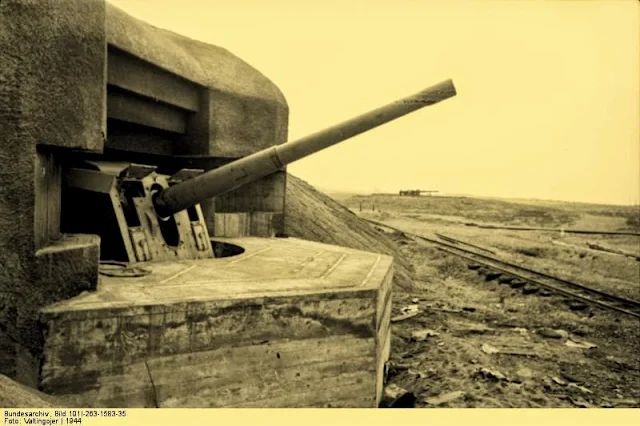

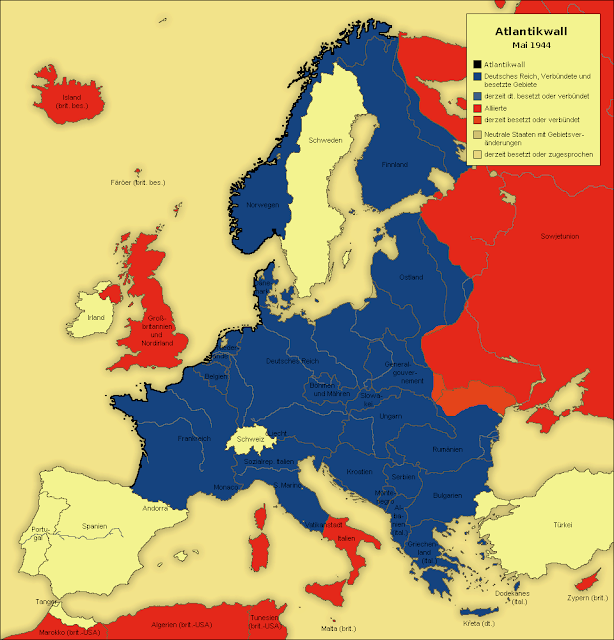

The Atlantic Wall (Atlantikwall) was an extensive series of coastal fortifications constructed by Nazi Germany between 1942 and 1944. The works covered almost the entire length of the coast of western Europe and were intended to dealing with the expected landing of the Allies in it based on Great Britain.

Historical Background

In May 1940, Germany invaded France and placed under its occupation and control the coasts of the entire northern part of the country. There was also a British expeditionary force in France, which gathered in Dunkirk and managed to escape with the "Dynamo" operation, losing only its equipment. After this event, Hitler believed that he would come to an understanding with the British, but they rejected the proposal. Unable to carry out his intention to invade Britain, he was forced to maintain a defensive posture along the European coast.

In the summer of 1941, Hitler invaded the Soviet Union. He used very large forces for this invasion with the consequence of almost stripping western Europe, where about a dozen divisions remained. As German officers believed that the Allies would make a landing on the western European coast to force Hitler to withdraw forces from the Eastern front thus relieving the Soviet forces. These fears were reinforced when in December 1941 the US declared war on Japan, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Hitler, following the pact he had made with Japan, in turn declared war on the USA. Aiming to prevent such action the Germans began to construct a series of fortifications initially along the French coasts closest to Britain. This fact encouraged the British, who attempted to disable the repair tanks of the French port in the Atlantic of Saint-Nazaire.

The goal of the British was that the Germans would not have shipbuilding repair facilities for the large surface vessels, such as the Tirpitz, in the Atlantic but would be forced to resort to facilities in Germany. This operation was a success, as the tank was rendered useless by the sinking (by explosion) of the old destroyer HMS Campbeltown. But it cost the British losses in material and men: 18 smaller vessels were sunk, and only 228 men returned to Britain. 169 were killed and 215 were captured.

After this event, Hitler issued Order No. 40, marking the official start of construction of the Atlantic Wall. Initially the fortifications covered the areas around the French ports. In August 1942 the Canadians, supported by British commandos and forces of the Free Poles attempted to land at Dieppe.

This effort failed and Allied losses were significant: 3,367 Canadians killed, wounded or captured, 275 British commandos and 550 British sailors. In terms of material the British lost 33 landing craft, one destroyer and 106 RAF aircraft. The Germans lost 591 men and 48 aircraft. After this effort, the German efforts intensified. The fortifications began, from 1943, to expand along the entire coastline.

The actual construction began in the spring of 1942 and for this purpose the Tot Organization was used. The works included extensive minefields, concrete walls, fortifications and machine guns made of the same material as well as fortified large gun emplacements, barbed-wire fences, flamethrowers and extensive anti-tank barriers. " (Festung Europa) and, while initially priority was given to the areas opposite Britain, the effort extended from the coast of Norway to the French border with Spain.

Even to the most ignorant, it was clear that such an effort would be completely impossible to complete, not only because there was a lack of labor but, above all, because there was a lack of materials. For example, the average sector requirements of the 343rd Infantry Division in 1943 were 40 concrete trains. Of these it was possible to deliver only 20 due both to a lack of raw materials and to transport difficulties caused by Allied air raids and, later, French guerrillas.

An important obstacle was also the lack of understanding between the German forces. The Navy had requested that even the toilets in the naval facilities be fortified with concrete, at a time when there was no concrete available for the fortified facilities on the coast. The situation changed very slowly, only at the end of 1943. An additional problem was the inability to provide adequate camouflage to the structures.

Despite the fact that the Germans had recognized the problem in time, they did not manage to solve it successfully - how could they hide the water ditches and fortified shelter structures from enemy reconnaissance? They limited themselves to taking into account that the Allies would know the positions of their fortifications.

Cornerstones of the Wall were the occupied British Channel Islands, the submarine bases and some very important ports, which acquired important fortifications in the form of fortresses, they were even called "fortresses" (Festungen) due to their special importance as possible targets for eventual landing. Coastal artillery consisted of 28 guns of different calibres, from 7.5 cm to 40.6 cm.

Due to the shortage of new guns, guns from decommissioned Navy ships and also from spoils of older operations from France, the Czech Republic were used even Soviet guns as well as old remnants of the First World War.

The German military command (OKH, Oberkommando des Heeres) expected a possible landing in the areas that presented the closest proximity to the British coast. For this reason, the strongest fortresses were built in this area, while the most remote areas were left either insufficiently fortified or completely unfortified. This was the case in the area of the Gulf of Seine, between Havre and Cherbourg, an area covered by only 47 artillery pieces, in contrast to the much less extensive area of the Pas de Calais, which was covered by 132 artillery pieces.

In late 1943, Hitler restored Field Marshal Erwin Rommel to active duty and placed him in command of Army Group II along with responsibility for the defense of Normandy, which included overseeing the Atlantic Wall in the region. Rommel toured the facilities in his area of responsibility, which he found to be completely inadequate. The Marshal decided to improve the fortifications of his area: Some forts were strengthened, the barbed-wire fences were improved, the minefields were enlarged and reinforced, while all kinds of anti-tank and anti-landing obstacles were placed on the coasts.

Flat fields were flooded and staked so that they could not be used as makeshift airfields or parachute landing fields. These are the famous "Rommel's asparagus" (Rommelspargel). Rommel realized - and rightly so - that the fortifications of which he was put in charge were not going to stop a large-scale organized landing. The most he could hope for was that these defensive works could delay the invaders and cause considerable confusion to their forces.

He was of the opinion that the landing parties should not be allowed to establish a bridgehead because, if they succeeded, from there almost unlimited forces in both men and material could be drawn into the conflict. What Rommel sought was a direct response to the invaders by his troops and especially by his armored units. His belief was that the Allies had to be confronted and defeated on the coast, or the cause was to be considered lost.

However, Rommel is very optimistic. The forces he commands are far from "remarkable". Most of his divisions include soldiers slightly amputated in other battlefields, men suffering from respiratory, visual, auditory and other types of disorders, while their officers are one-eyed, one-handed, lame, and their average age is from 50 to 60. The 70th Division consists entirely of men who suffer from their stomachs and need special food and diet bread.

Rommel's views are opposed by both the commander-in-chief of the Western armies, Gerd von Rudstedt, and the commander of the armored forces, Geir von Schweppenburg. Both (especially the second) believe that the landing in the West will develop into a major armored battle, which will decide the outcome of the operation. No one is justified. The Führer will personally direct the battle of the West. On one point, however, his views agree with Rommel's:

While on the vast eastern front the loss of ground is acceptable up to a point, on the west this is absolutely unacceptable. The German troops must not retreat and give "not an iota of ground". For this ultimate goal, there is a specific reason. The launch sites for the V1, V2 and (later) V3 flying missiles are close to Britain and their loss means the loss of an important - in the Führer's view - German weapon.

Rommel is also confronted with the reality of building materials and the effects of their lack. While Hitler had requested that by the end of 1943 the Toth organization would have 15,000 concrete fortified emplacements ready, only 5,000 had been prepared by almost mid-1944. Shelters for most of the guns had not been built, the materials for building mines were lacking. . Rommel resorts to his imagination and does not economize either on his strength or his efforts.

He builds barriers out of wood (the steel is missing), plants them on beaches flooded by the high tide, and equips them with steel blades to rip through the reefs of the divers. He uses old rails to build a type of anti-tank obstacle. It calls for about 300 million mines to be built to turn the beaches into deadly minefields. One hundredth of them succeed.

Only 2 - 3 million mines are available, there are neither metals nor, above all, explosives to charge them. Rommel's efforts and constant, feverish movements are described in detail by Rear Admiral Friedrich Ruge (Friedrich Ruge) and Major General Dihm (Dihm), assistants to the Field Marshal, in a statement they gave under interrogation by the American forces. In addition to materials, labor is also starting to be lacking.

The Tot organization is not only concerned with the Atlantic Wall, it has also been tasked with the bases for launching the flying bombs but also with the difficult task of maintaining the railway network and repairing the damage caused by Allied bombing. Some large units are "reinforced" with engineer battalions and even the force of 2,850 men is drafted in from the French Labor Service.

Only one workforce remains. That of the infantry soldiers themselves, who are "recruited" to carry out fortification work. As a consequence, they do not perform exercises and the combat value of their units is significantly reduced. The results remain meager. The 709th Division, covering a section of the Normandy beachhead, has a single concrete fort instead of 42 planned.

A fortress can withstand ground forces. But how would the rest be treated? Coastal artillery was planned for the Navy, as the Kriegsmarine was not expected to participate, for the simple reason that it no longer had surface ships. His biggest ships were (at least these) destroyers. Anti-aircraft and aircraft were needed for the Air Force. And Albert Speer had succeeded in increasing the production of aircraft, but aircraft need pilots and fuel.

The Luftwaffe no longer possesses either. The growing shortage of fuel forces prospective pilots to train from 100 to 50 hours only, due to lack of fuel. Training accidents are almost equal to war casualties. The Luftwaffe is conspicuous by its absence on the Western Front. Allied superiority in sea and air is taken for granted by the Germans.

Moreover, the "first teacher" of blitzkrieg with paratroopers, Hitler, does not take into account their existence in the opposing camp at all, despite the fact that his loyalist Alfred Jodl pointed it out to him, proposing to give depth to the coastal defense of the peninsula of Cotantin for a possible landing of airborne forces.

Rommel had under his supervision and administration only the supervision and adequate organization of the construction of the Wall. His command was divided into eight areas:

Norwegian Military Command

Danish Forces Command

German Gulf Command

Wehrmacht Command in the Netherlands

High Command 15 (15th Army Zone)

High Command 7 (7th Army Zone)

High Command 1 (1st Army Zone)

High Command 9 (Zone of the 19th Army)

This division had been imposed by Hitler himself, who, as mentioned above, wanted to command the troops that participated in the western front himself.

Major Fortifications

of Cherbourg: The main port of Normandy was well organized and the commanding general Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben had 47,000 men on the Cotantin peninsula. The port had been undermined and before it could be surrendered its central facilities were blown up. It returned to partial operation in August 1944.

Saint-Malo: Commanded by Colonel Andreas Maria Karl von Aulock who had 12,000 men in total resisted, on the fortified islet of Cézembre and after capturing the main port to surrendered due to lack of ammunition on 2 September 1944. Von Aulock, when initially asked to surrender after the landings, replied that he would defend Saint-Malo "to the last stone".

Alderney: The northernmost of the Channel Islands was so well fortified that it was surrendered only after the surrender of Germany (8/5/1945).

Brest: Very well fortified, it held out under General Hermann-Bernhard Ramcke until September 2, 1944. The port was completely destroyed.

Lorient, Saint-Nazaire, La Rochelle (in nearby La Palis) (German U-boat bases in France): Surrendered only after the surrender of Germany (8/5/1945).

Havre: Surrendered after three days of hard fighting with the port half destroyed, on 14/9/1944. The port reopened in October 1944.

Boulogne: Hostilities began on 7 September, surrendered on 22/9/1944, the port reopened in October.

Dunkirk: Although isolated from September 13, 1944, it was surrendered only after the surrender of Germany (8/5/1945).

Calais: Coastal artillery surrendered in mid-September, Calais and Cap Gris-Neis on 30 September.

The Mulberry Harbors were two prefabricated temporary ports built by the British on two of the beaches of the Normandy landings in 1944. The main purpose of these ports was the sea support of the disembarked forces with war material, fuel and food.

A key problem of transport - mainly of material - was the lack of suitable ports in the region. The major ports (Cherbourg, Havre, Calais) of Normandy were held by the Germans and it was utopian to ask for their occupation (in good condition) before or during the landing, as Cherbourg and Havre were in fact excellently organized defensively.

It was therefore decided, following Churchill's idea, to build two "prefabricated" ports, which were called "Mulberry harbors". One in Omaha Beach (Mulberry "A") and one in Arromance (Gold Beach) (Mulberry "B"). The idea was simple. The prefabricated floating metal sections would be towed to the French coast and there they would be fixed with the help of concrete sections and connected by metal walkways to the shore.

The superstructure would be added later. Construction time required. Just two weeks. The capacity of each was calculated to be equal to that of the port of Dover. These ports were indeed built, but on June 19, 1944, a storm of great intensity destroyed large parts of them. In the American zone it was decided to abandon it, in the British zone it was repaired and continued to be used until the completion of operations.

Initial Design

With the tragic outcome of the Dieppe raid in 1942 as an example, the Allies had realized that simple air superiority and support for the landing forces during the Normandy landings was anything but satisfactory. The Germans had organized the Atlantic Wall, the defense of which could only be neutralized by a sufficient number of combat units, which would have the necessary equipment and could be supplied at an uninterrupted rate.

It was obvious that this could only be secured by sea, but the Germans had impeccably fortified the two largest and principal ports of Normandy, Cherbourg and Le Havre. Because of these fortifications (which covered the ports and port facilities) the Allies had to consider other ways of moving the huge quantities of materiel required by the (then possible) Normandy landings, especially during the first days of the landings.

Thus, the British, already in 1941, had set up a small group of engineers, under the name of "Transportation 5 (abbreviated Tn5) whose initial object was to develop methods for the rapid rehabilitation of damaged ports. The British proposed to "transport" the their own port along with the landing forces.The plan received the support of the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.Thus, with the prime ministerial support, the construction of the man-made ports began immediately in Britain.

Also involved in the project was Professor Bernal (JD Bernal), who later helped significantly in the final design of the artificial harbor. Bernal was greatly assisted by Allan Beckett, whose plan to build vehicular traffic at the mobile port "qualified" over the others. Of course, in a construction of similar complexity and size, it is utopian to look for the authorship of the final result in one man can only be mentioned those who expressed the central ideas of the overall construction.

Of the initial designs submitted, three were selected for further evaluations in practice.

- The first, created by the Ministry of War, provided for flexible constructions, in the form of floating bridges such as those constructed by the Corps of Engineers, supported on pairs of steel or concrete, with piers that had adjustable support legs, so as to cope with the differences in water level by the tides.

- The second plan was submitted by the British Admiralty and provided for flexible floating structures made of wood and hemp cloth, the individual parts of which would be assembled with the help of wire ropes.

- The third plan, submitted by Hughes, provided for the use of metal "bridges" that would rest on concrete supports, be towed to the intended positions and be dumped there. Initially no plans included the creation of breakwaters. Test beaches similar to the Normandy beaches were then sought.

After exhaustive research, Wigtown Beach in the Solway Firth region of Scotland was chosen, with the nearby port of the town of Garlieston and the entire beach from the town to the location of the Isle of Whithorn (Isle of Whithorn, which is actually not an island, in spite of its name) was excluded from all but the fishermen of Garlieston.

Work began with the establishment of a camp at Cairnhead to accommodate the engineers working on the test program and an additional 200 men for the work. The original design, as mentioned above, did not provide for protective breakwaters. But this required the establishment of ports in areas with calm waters. However, two "ways" were created to deal with any strong ripple.

The first consisted of stringing perforated pipes through which compressed air was passed, which created bubbles capable of stopping the ripple, and the second was the construction of canvas from large sacks with a total "thickness" of seven meters. The bags were filled with air at low pressure and absorbed the energy of the wave as it compressed them.

During the final planning, it was decided to build two such ports. One was intended for the American sector of operations at Omaha Beach and was designated "A" and the other would meet the needs of the British Canadian sector of operations on the Arromanches coast. Originally named "B" but nicknamed "Winston" (after Churchill). Finally, it was decided to build breakwaters, as they were deemed necessary. One group would be submerged in the middle of the sea and one along the coast.

It would consist of concrete blocks with iron reinforcement but for extra protection 70 useless or obsolete vessels, commercial or war, would be used to cover the gaps that would appear between the blocks. In the whole process of the final design Hughes participated as a consultant, invited by Churchill himself.

Each of the artificial harbors would have a total of six miles of flexible steel access roads supported by concrete piers. These "roads" were called "whales" while the concrete pairs were called "beetles". The roads ended at giant jetties on the (sandy) shore. The materials required were enormous in quantity. Each port required 144,000 tonnes of concrete, 85,000 tonnes of ballast and 106,000 tonnes of steel

Site Surveys

The success of the entire undertaking rested on accurate and detailed topographical information about both the site sites and the small French coastal towns. Aerial photographs were taken as a first step, but the British government asked for the help of the common people in order to obtain more detailed information. Every photograph and postcard received by British citizens on French beach holidays was precious.

Again, however, the information was deemed insufficient, as local conditions, such as the surface composition of the beaches, any dikes covered by sea water, tidal conditions and other related matters and, above all, the coastal fortifications of the Germans, did not it was possible to cover them from the photo shoots. The assistance of the espionage services was called in, as there was no margin for error.

So on New Year's Eve 1944 Engineer Major Logan Scott Bowden and a group of his men boarded a small torpedo boat and, off the coast of Lyc-sur-Mer, transferred to a Hydrographic Service vessel. Bowden and Sergeant Bruce Ogden-Smith swam ashore and collected samples of sand, silt and gravel, which they stored in numbered tubular containers.

Based on this information, two scale models were constructed, one in room 474 of the "Great Metropole Hotel", which was closed by the War Department, and one in the prime minister's office. In the Cairnryan area of Scotland an attempt was made to create the French beaches (always based on the information gathered) to test as adequately as possible both the effectiveness of the landing techniques and the movement of men and vehicles during the landing.

Construction

After testing was completed, the individual parts were approved for construction, which was undertaken by around 200 companies across the UK. Grouting initially began on a strip of land in Leith, while other areas where construction was taking place were Conway in North Wales and Cairnryan in Scotland, where construction was entirely undertaken by the British Army.

The "roadbed" was built in such a way that it could be towed for about 100 miles and withstand the weather conditions prevailing in the English Channel during the summer months. They passed through arches about 25 m long each, which were supported by floats. Each such arch rested on 25 m bases and its pavement was 3 m wide, while the whole weighed about 30 tons. The whole structure showed great flexibility that each part of it could be rotated forming an angle of 40° with the next, but the portability remained the same.

It could support the heaviest military vehicles at speeds of 25 mph. In this way, a circular sector was created, in which, due to the breakwaters, the waters would be calm and it would be possible for ships to unload at the piers (they were called "whales") The breakwaters had, in turn , called "phoenix" and carried an anti-aircraft turret.

Final Construction and Use

All the necessary elements were transported one by one to the two locations that had been chosen (Arromance and Saint Laurent sur Mer) with the help of tugs in order to begin assembly immediately. .The first tugs arrived ashore on the morning of June 6th and their radios pick up signals from Omaha Beach that speak of strong German resistance and at first it appears to them that the landing is failing.

However, by the evening of 6 June the area of Arromanches has been cleared of enemy fire and assembly of the harbor begins with the creation of the breakwater. Construction is almost complete the next day, and so is the second port in Saint Laurent. The Allies use the ports as soon as the construction is completed and this use continues for eight consecutive days, as Cherbourg is late to be captured but also its facilities are rendered useless by German sabotage.

The port of Arromance, in the British zone of responsibility, more protected, was also damaged, but was deemed repairable. The British actually repair it and continue to use it for another month, with a daily output of 10,000 tons of material. Cherbourg has been occupied since 26 June, but sabotage repairs keep her out of service until 27 July 1944, when the first Allied ships approach her.

The ports of Mulberry have served their purpose of supplying war material and supplies to the attackers until one of the great ports of Normandy can be used. About 2.5 million soldiers, 500,000 vehicles of all types and 4 million tons of material were transported through them. The port of Arromance continued to be used until 19 November 1944.

THE GREATEST DAY OF THE WAR

THE LANDING PLAN

The landing was decided to take place in four different sectors (beaches) initially. A fifth (Utah Beach) was later added on the grounds that it was too close (only 60 km) to the large and important port of Sherbury. At the two westernmost (Utah Beach and Omaha Beach) Americans would land, at the third (Gold Beach) British, at the fourth (Juneau Beach) Canadians and British and at the fifth, easternmost (Sword Beach) British and a small unit of "Free French" .

The forces of each sector had specific objectives. At the same time, the 82nd and 101st American Airborne Divisions, the 6th British Airborne Division and the 1st Canadian Parachute Regiment would be parachuted in, while troops would also be airlifted by gliders. The crossing of the English Channel and the assault phase of the landing were codenamed "Operation Neptune".

The Normandy coast is characterized by high tides. In order to land all forces under the same conditions, the landing time at Omaha and Utah Beach was set at 06:30, while the British and French forces were scheduled to land between 07:00 and 08:00.

THE NIGHT BEFORE DEPARTURE

The most terrible enemy for the paratroopers in those early hours was not man, but nature. Rommel's anti-parachute measures had worked well. The waters and swamps of Diw's flooded valley were death traps. Some pilots had made a mistake in orientation and dropped the paratroopers over the swamps. The number of men who drowned in the waters of the Div has never been known. Ingenuity alone has been the means of survival for many paratroopers.

It was the feeling of self-preservation that saved many from incredible ordeals. The Germans thought that Sainte-Mer-Eglise was flooded with paratroopers. In fact about thirty Americans fell into the city and only about ten landed in the square. But they were enough to cause the panic of the hundred or so men of the German guard. The paratroopers dropped like ghosts from the sky, in addition to terrorizing the Normans, they also created confusion and panic among the Germans.

Some scouts, searching the Normandy night near cottages or on the edges of villages, were trying to get their bearings. Those who had dropped accurately went, immediately, to the appropriate areas to carry out their mission. In the drop zones, lights began to come on for the upcoming airstrikes. German Major Werner Pluskat, dazed and jolted awake by the noise made by the planes, jumped from his bed in alarm.

His instinct made him feel that this was no ordinary airstrike. Two years on the Russian front made him rely on his instincts. After the commanding colonel answered on the phone that he did not know what was going on, he took his wolfhound and with two other officers of his staff went to their advanced headquarters, an underground fort of observation on the rocks above the coast, which it would later become known as Omaha Beach, near St. Honorine.

With the powerful artillery scopes he carefully surveyed the sea that shone from the bright moon, when it was not covered by clouds, without noticing anything unusual. "There's nothing out to sea," he called regimental headquarters. Vague, incomplete and scattered information reached the headquarters of the 7th Army units throughout Normandy, without anyone being able to draw a positive conclusion that would lead to an alarm signal.